Our founders

There’s a joke that in any bar in Vancouver, Canada, you can sit down next to someone who claims to have founded Greenpeace. In fact, there was no single founder: name, idea, spirit and tactics can all be said to have separate lineages.

Yet, some people clearly stand out. Here are four of them.

Our history, victories and successes

View a timeline and take a look back at some of the positive environmental changes from the Greenpeace network.

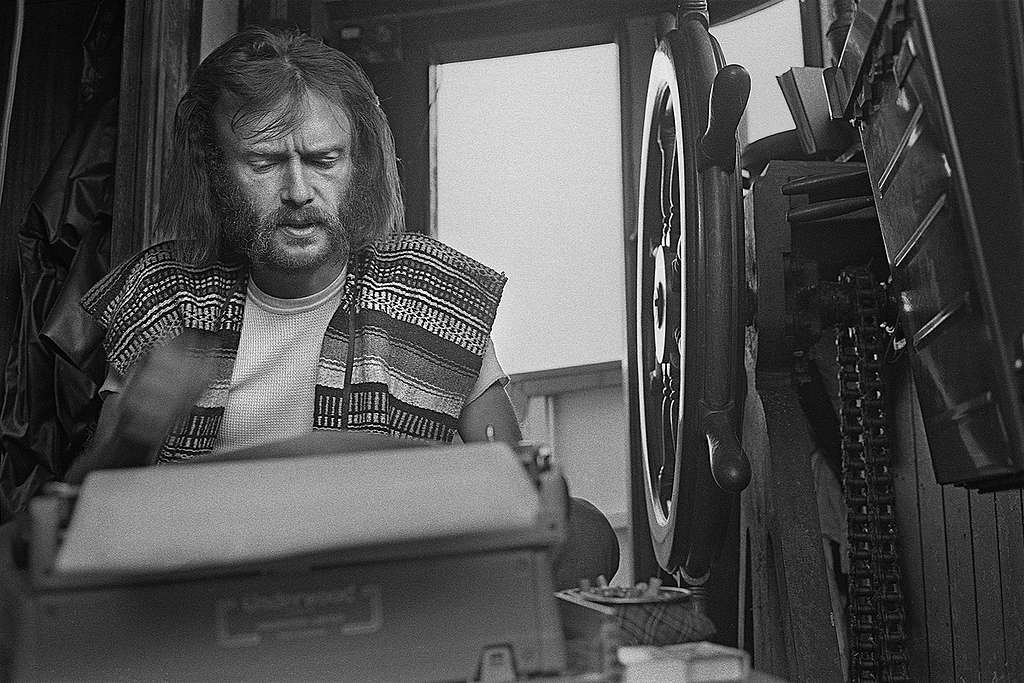

Bob Hunter (1941–2005)

He was a relentless visionary and a mystic storyteller – the Canadian Bob Hunter infused the young Greenpeace with a magic that lasts to the present day.

From day one, the long-haired, beardy journalist, who introduced the Cree Indian myth of the “Warriors of the Rainbow”, forced those around him to think big – and then go one step further. For Hunter, the limits of the practical or the probable didn’t count: Nothing was ever impossible.

Combining creativity with strategic thinking and a hard-nosed journalistic sense for a good story, he helped to shape – perhaps like no other founding member – what would come be known, around the world, as a “Greenpeace action”.

Fascinated by media theory, the often audacious Hunter wanted to change the world with “media mindbombs” – consciousness-changing sounds and images that would blast around the world in the guise of news. The approach worked brilliantly. Greenpeace quickly became a media household name around the world.

Hunter’s spirit of courage, defiance and media-savviness continues to define Greenpeace up to the present day. The organisation he co-founded and shaped in a way few others have, will always be blessed with his spirit.

Bob Hunter died of prostate cancer on 2 May 2005, aged 63.

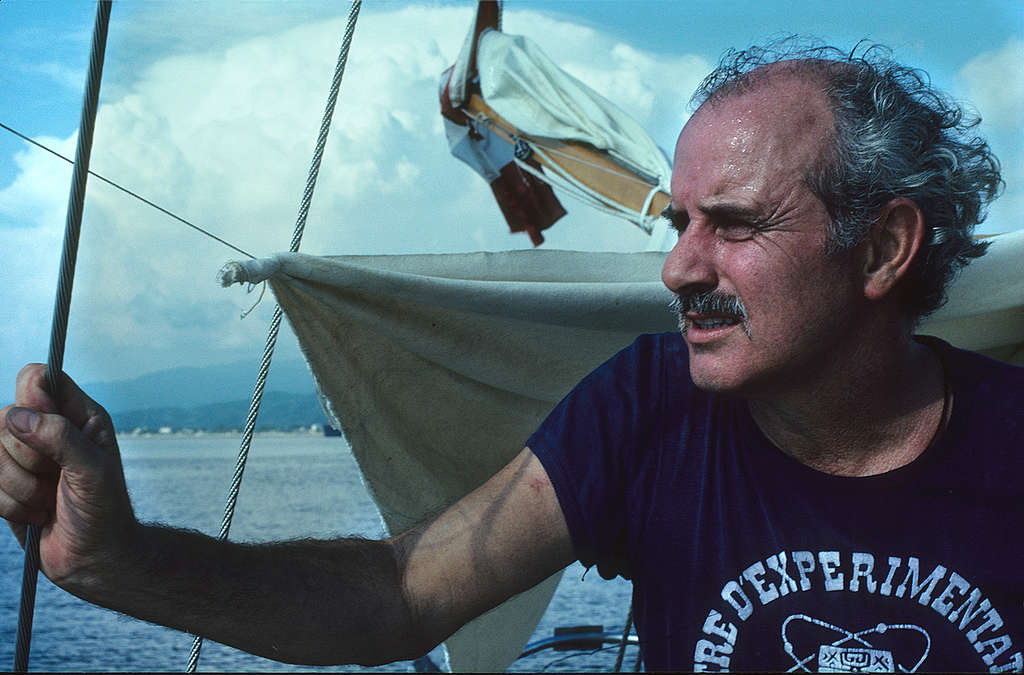

David McTaggart (1932–2001)

He was pragmatic, driven and famously ruthless – David McTaggart took Greenpeace’s free-spirited founding ethos and translated it into an international organisation.

Responding to a newspaper ad placed by a newly-founded group called Greenpeace, the Canadian-born former entrepreneur promptly renamed his sailing boat “Greenpeace III” and set sail to confront a French nuclear weapon test.

It was what would become known as “classic Greenpeace” – a tiny boat challenged one of the greatest military forces on Earth.

McTaggart’s pragmatism and shamelessly entrepreneurial approach built the organisation Greenpeace. Soon after joining, he began drumming up new support throughout Europe, and in 1979 forged a new international alliance, uniting the organisation’s separate factions: Greenpeace International was born.

The founding ethos was framed long before McTaggart came on board, but the relentless Canadian defined the growing movement’s structure and its methods like no other. By 1985 the organisation that started life on a small fishing boat had three ships and 50 campaigns around the world.

Today, Greenpeace’s integrated structure means that global problems can be addressed at a global level. The foundations for this were laid by the man who sailed off on a whim – only to end up dedicating his entire life to environmental issues.

David McTaggart died in a car accident on 23 March 2001 near his home in Italy.

Dorothy (1920–2010) and Irving Stowe (1915–1974)

As committed pacifists and life-long activists, Dorothy and Irving Stowe didn’t have to think twice when the idea came up to sail a boat into a nuclear test zone.

Their tolerance united the Don’t Make A Wave Committee that discussed the plan; their experience inspired it. Their peaceful, committed spirit became the group’s. And that group became Greenpeace.

“It is amazing,” Dorothy Stowe would later recall, “what a few people sitting around their kitchen table can achieve.” It was here that the disarmament movement got to know its nascent ecology counterpart – and it was the charismatic Quaker couple that hosted the meetings that held the loose, often disparate alliance of dreamers together.

The Stowes brought ideas to the table that would become an essential part of the Greenpeace founding ethos. “Bearing witness”, they explained to the group, was a sort of passive resistance: You go to the scene of an objectionable activity to register your opposition by your presence.

From the example of Gandhi, the Stowes believed that citizens acting with integrity and courage could defeat powerful forces. To this day, Greenpeace is “bearing witness” and “speaking truth to power”.

Irving Stowe died of pancreatic cancer on 28 October 1974, aged 59 – only two years after Greenpeace was founded.

After a life dedicated to campaigning for civil rights, women’s rights and the environment, Dorothy passed away on 23 July 2010 in Vancouver, Canada, at the age of 89.

The Don’t Make A Wave Committee

In 1970, the Don’t Make A Wave Committee was established; its sole objective was to stop a second nuclear weapons test at Amchitka Island in the Aleutians. The committee’s founders were Dorothy and Irving Stowe, Marie and Jim Bohlen, Ben and Dorothy Metcalfe, and Bob Hunter. It’s first directors were Stowe, Bohlen, and a student named Paul Cote.

Canadian ecologist Bill Darnell came up with the dynamic combination of words to bind together the group’s concern for the planet and opposition to nuclear arms. In the words of Bob Hunter, “Somebody flashed two fingers as we were leaving the church basement and said “Peace!” Bill said ‘Let’s make it a Green Peace.’ And we all went Ommmmmmmm.” Jim Bohlen’s son Paul, having trouble making the two words fit on a button, linked them together into the committee’s new name: Greenpeace.

Marie Bohlen was the first to suggest taking a ship up to Amchitka to oppose the U.S. plans. The group organised a boat, the Phyllis Cormack, and set sail to Amchitka to “bear witness” (a Quaker tradition of silent protest) to the nuclear test. On board were: Captain John Cormack, the boat’s owner), Jim Bohlen (Greenpeace), Bill Darnell (Greenpeace), Patrick Moore (Greenpeace), Dr Lyle Thurston (medical practitioner), Dave Birmingham (engineer), Terry Simmons (cultural geographer), Richard Fineberg (political science teacher), Robert Hunter (journalist), Ben Metcalfe (journalist), Bob Cummings (journalist), Bob Keziere (photographer).

Stowe, who suffered from sea-sickness, stayed on shore to coordinate political pressure. Cote stayed behind too, because he was about to represent Canada in an Olympic sailing race.

Bob Hunter would take the lessons of that first voyage forward and improvise upon them to the point that he, more than anyone else, invented Greenpeace’s brand of individual activism.

The Amchitka voyage established the group’s name in Canada. Greenpeace’s next journey spread their reputation across the world.

Amchitka: the founding voyage

In 1971, a small group of activists set sail to the Amchitka island off Alaska to try and stop a US nuclear weapons test. The money for the mission was raised with a concert, their old fishing boat was called “The Greenpeace”. This is where our story begins.

Life on a Greenpeace voyage always involves a lot of colourful characters, strong opinions, good times and bad. Obviously at this point Bob was not in the greatest of moods and chose a novel and non-violent, if not entirely non-offensive, way of showing it.

“Why not sail a boat up there and confront the bomb?”

It was a fancy, at first. Marie Bohlen casually expressed the idea over coffee one morning. But the people around her – a lose alliance of Quakers, pacifists, ecologists, journalists and hippies – weren’t known for shrugging off the really big ideas.

A few weeks later, the Don’t Make the Wave Committee – as the group was still called then – had a plan. “If the Americans want to go ahead with the test,” Marie’s husband Jim said, “they’ll have to tow us out.”

Leaving one of those heady first meetings, Irving Stowe flashed the peace sign – as was his custom – and said “Peace”. On that occasion, the usually rather quiet Canadian ecologist Bill Darnell made the off-hand reply: “Make it a green peace.”

When the words didn’t fit onto buttons for the group’s first fundraiser, they were simply merged: Green Peace became Greenpeace.

The concert

We had our name, but it was soon clear that selling 25-cent buttons wouldn’t bring in the cash needed to buy a boat. Someone had the idea to put up a rock concert.

A few phone calls later, Joni Mitchell said she would be playing. Chilliwack and Phil Ochs confirmed, before Joni called again to say she would bring a special guest: James Taylor. None of them wanted any money for the night.

“The concert was a sell-out, the biggest counter-culture event of the year,” Rex Weyler recalls in his Greenpeace biography. The sixteen thousand that filled Vancouver’s Pacific Coliseum left the concert entranced.

Afterwards, attendance at the meeting swelled, the money started to pour in. By the end of October, the group had raised more than $23,000. Greenpeace was ready to go.

The voyage

Yet, the voyage was a disaster. The boat left the harbour at dusk on 15 September 1971, but internal tensions soon flared up.

“We never quite managed to go in the direction we wanted to go, or be in the place we wanted to be. And we fought bitterly among ourselves about it. Everything we did or said got sucked into an overwhelming power struggle.”

“Here we were, supposedly saving the world through our moral example, emulating the Quakers, no less, when in reality we spent most of our time at each other’s throats, egos clashing, the group fatally divided from start to finish.”

Even worse, “The Greenpeace” was intercepted by the US navy, before it even got close to the Amchitka testing site.

Failure looks different, however. The Amchitka voyage sparked a flurry of public interest. The media went wild about the small group of activist who had sailed off in the face of great adversity – the first “media mindbomb”, as Bob Hunter conceived of those early Greenpeace actions, had been launched.

The beginning of a much bigger story

“As it turned out, all my angst was unnecessary,” he later wrote. “Time has proven my post-trip despair to be utterly mistaken. The trip was a success beyond anybody’s wildest dreams.”

The nuclear bomb the group had come to stop went off, but the tests planned for after that were cancelled. Five months after the group’s mission, the US stopped the entire Amchitka nuclear test programme. The island was later declared a bird sanctuary.

“Whatever history decides about the big picture, the legacy of the voyage itself is not just a bunch of guys in a fishing boat, but the Greenpeace the entire world has come to love and hate.”

Today, Greenpeace is the world’s most visible environmental organisation, with entities in more than 55 countries and over 2.9 million members worldwide. Amchitka, it has turned out, was only the beginning of what would come to be a much bigger story.

Bob Hunter’s account

Bob Hunter sailed aboard the first Greenpeace voyage in 1971 to Amchitka in the Aleutian Islands to try and stop a U.S. nuclear weapons test. When they were halfway to their destination, Richard Nixon announced a month’s delay of the test. Most of the crew were running out of money or vacation time, and an acrimonious debate broke out about whether to continue or turn back. This is Bob’s story about what happened. Read Bob Hunter’s first hand account of the voyage

Additional Reading:

For more information on the founders and the first ten years of Greenpeace we refer to the book “Greenpeace: The Inside Story: How a Group of Ecologists, Journalists and Visionaries Changed the World” by Rex Weyler.