How does an eager engineering student, in the era of expanding space exploration, become an ecologist, dedicated to the Earth? In my case: Rachel Carson, the Cuyahoga River, Gregory Bateson, Fools Crow, and a magpie.

In 1966, I enrolled as a physics and math student at Occidental College in Los Angeles. Like most of the students, I felt a great anticipation about space exploration and the discoveries of astrophysics. During the summer after my first year, I got a job at Lockheed Aerospace as an apprentice engineer.

However, that summer of 1967, I also read Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. Carson’s book, written five years earlier, examined thirty-five bird species threatened with extinction due to chemical pesticides, including organo-chlorines such as DDT. I knew just enough chemistry to know she was speaking the truth, and when the chemical companies attacked her, I knew they were lying.

In the 1950s and 60s, the US military funded research into synthetic pesticides, and the US Department of Agriculture attempted to eradicate fire ants with a mixture of DDT and fuel oil, a precursor to Agent Orange used by the US military during the Vietnam War. Carson called the government’s claims about the concoction, “flagrant propaganda.”

When Carson attended government hearings, chemical industry lobbyists attacked her data and promoted their own witnesses to contradict her research. However, working with medical researchers, Carson documented individual incidents of pesticide exposure, human health effects, and environmental impact.

In Silent Spring, Carson not only exposed the ecological impact of these toxins, but she called into question the entire paradigm of human progress. Working in the aerospace industry, I never knew precisely what I was working on, everything being top secret. I began to see how science could go wrong, not only with the dangers of nuclear weapons, but by flooding our ecosystems with toxins. I returned to school in engineering, but now harboured some burning questions about ethics, ecology, human health, and the role of science.

I was not, however, quite prepared for the next shock to my system.

The burning river

In the summer of 1969, after my third year of university, I saw a picture in the Los Angeles Times, of firemen putting out a fire in Cleveland, Ohio. However, this was not a typical building on fire, or forest fire. I stared at the printed page. What? The river is burning? How does a river burn?

The Cuyahoga River flows from the highlands northeast of Cleveland, moves south for about 80 kilometers, fed by dozens of tributaries, turns north, and flows 70 km through lush Cuyahoga Valley and Cleveland, into Lake Erie between the US and Canada.

The Cuyahoga River, however, had been so polluted with oil and chemicals, that it routinely caught on fire. The incident in 1969 was the 13th fire on the river. A 1912 fire killed five people, and a 1952 fire caused over $1.3-million in damages (over $10-million today).

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring alerted me to think about ecology, but the Cuyahoga River fire rocked my world. The river fire felt apocalyptic, primal, like a sign from Humbaba, the forest protector in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Earth, air, fire, and water. I felt that perhaps science, per se, was not the cause of these problems, but that the dysfunction emerged from our economic and political policies that used scientific discoveries to bolster profits, without considering or accounting for the unintended consequences.

I gave up the idea of being an aerospace scientist, left school, and set out to become a journalist, so I could research and write about the challenges humanity was facing. I felt that society needed to pay a lot more attention to the wild, natural world, and to learn how wild ecosystems actually work. These ideas led me to another breakthrough.

Mind and nature

I lived in San Francisco for a while and heard stories of a popular professor at the University of California at Santa Cruz, who was talking about ecology and complex systems. It might feel hard to imagine now, but ecology remained an esoteric idea in 1969. I started going to the lectures.

Gregory Bateson lectures were not like anything I had yet experienced in university. It seemed that he never quite summed things up. He would display various objects and ask students to describe which came from a living being, and how you knew. The spiral of an ammonite fossil gives it away as “life,” but are there non-living spirals in nature? What about hurricanes?

He would draw a strange picture on the blackboard and ask students to describe it. To do so, one could perhaps break it up into parts that looked like common objects. As students struggled with this, he said something that became a fundamental awareness for me, even to this day: “All divisions are arbitrary.”

Our language, nouns and verbs, divide the world into “objects,” but in the real world, nothing exists in isolation. Everything exists in relationship. We talk about a “tree” in “soil,” and the “atmosphere,” but none of these exist as they are without the others, and each one flows through the other, influences and changes the other. When I bite into an apple, when do the molecules of the fruit stop being an apple and start being me?

Bateson emphasized that to understand life, we had to understand “the pattern which connects,” the tree to the soil, to the atmosphere. “Schools” he said, “teach almost nothing about the patterns that connect.” What is the pattern which connects all the living creatures?

He talked about seeing “living beings with recognition and empathy,” staying aware and responsive to pattern and relationship. How am I related to the tree? What pattern connects me to the Red-tailed hawk or the prairie dog? Living forms, he suggested, have repetitive patterns, “rhythmical” the way dance or music is rhythmical, repetitive but with modulation. Without being explicit, Bateson was teaching students how to think about complex living systems, how to notice the deep symmetry and reciprocity in living relationships.

The pattern which connects us to the natural world is, in Bateson’s language, “a metapattern” a “pattern of patterns.” Nothing exists alone. All divisions are arbitrary. All life exists within these embedded systems and subsystems, trading resources, communicating, and learning together. Furthermore, since co-evolving systems include random factors – as do chess games or hurricanes – they are not entirely predictable, even if one knows the rules. Thus – and this our society needs desperately to embrace – systems themselves evolve, and new relationships almost always include unintended consequences. Each subsystem – organ, body, society – within an ecosystem co-creates a complex web of processes with its neighbouring subsystems. Nature is a web of relationships. Nature is not a collection of objects, but of processes. Our ecological efforts need to recognize and protect these complex relationships.

Bateson used to give students a test with two questions:

1. Define “entropy.”

2. Define “sacrament.”

As a physics student, I understood something about entropy, a characteristic of thermodynamic processes that tells us all organization, all information, in the universe requires energy to establish and maintain itself. Without energy flow, organization decays. Furthermore, when energy is used, some is lost. All used energy is dissipated. Without the sun, bathing Earth in energy every day, all life here would wither and die. Entropy was a complex observation of natural processes, but something I could imagine.

Sacrament is different. It has to do with perception, a relationship between observer and the world, a sense of what feels sacred and how to express it. Sacrament was even trickier than entropy. Sacrament had something to do with our relationship to the complex living system that was our world.

In his later book, Mind and Nature, Bateson explained that “sufficient answers for this test would imply a good grasp of human science and human culture, and would represent a good start in solving humanity’s problems.” Bateson often emphasized that “we have to learn to think the way nature works.” For me, he opened a door that led into a deep, non-human-centred ecology.

I thought for a long time about sacrament, and how that fit in.

The Mother

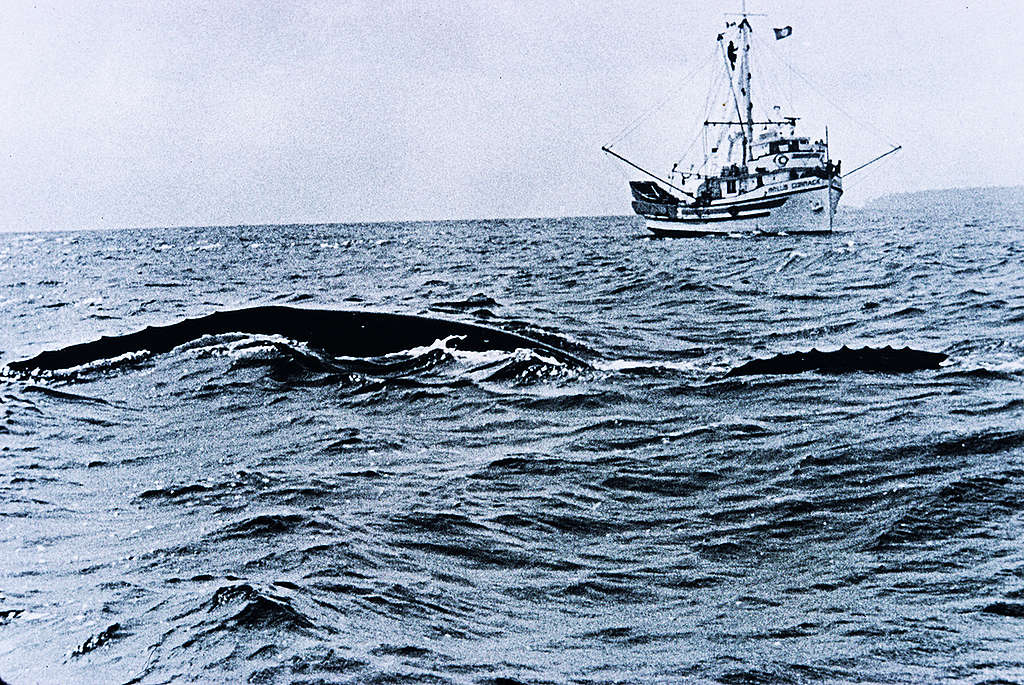

Out of school, I became eligible for the US military draft, but having heard stories from Vietnam veterans and deserters, I had no intention of participating in the horrific, senseless war. To avoid jail time, I went to Canada, where I met Bob Hunter, Irving and Dorothy Stowe, and others who were active pacifists and ecologists. We talked of starting a global “ecology movement,” on the same scale as the peace and civil rights movements. This group began as a pacifist movement, became Greenpeace, and in 1975 we sailed out of Vancouver to save whales by confronting whaling fleets, the organization’s first real ecology action.

In the 1970s, some of us in Greenpeace worked closely with Indigenous activists in Canada and the US. Bill Means from the American Indian Movement invited me to South Dakota to support the Lakota nation taking back some of their traditional land in the Black Hills. On the Pine Ridge reservation, Means introduced me to the elders, the grandmothers, and to Chief Frank Fools Crow.

In ceremonies, I noticed that the grandmothers held a special place, central but often quiet, allowing the younger relatives to conduct conversations and rituals. However, whenever conflict or confusion arose, the grandmothers stepped in to sort it out. This felt like a quiet sort of power.

I also noticed that speakers ended their statements or prayers with the Lakota “Mitakuye-Oyasin” (pronounced mi-TAHK-wee-a-say). I learned that this meant “all my relations,” and Fools Crow explained the deeper spiritual meaning. As a boy, the elder Chief said, he was taught that “every living thing is sacred, and that every living thing is our relative. The Earth is our Bible, our Church, our store, our security. When we pray, we say Mitakuye-Oyasin to remind ourselves that whatever we wish for ourselves, we must also wish for all our relatives, for all life.”

I met Richard Kastl from the Osage-Creek community in Oklahoma. He appeared as an imposing bear-like man, but with an aura of tranquility that seemed to draw tension out of the air, transforming it into peacefulness. He told me: “The sacred means that everything is in its proper order. Guns and bombs are not that great of a power. The natural world is the real power. The Mother holds the hammer.”

Years later, when Greenpeace worked with the Tsleil-Waututh nation in Canada to stop tar sands oil tankers in Vancouver’s harbour, I participated in weekly sweat ceremonies hosted by Tsleil-Waututh Sundance Chief Rueben George and his mother Ta’ah. Again, Rueben, Ta’ah, and the others ended their prayers with “All my relations.” George would say, “One heart, one mind, one prayer. We are all in this together, even the oil executives and their families. One family.”

Mitakuye-Oyasin. All my relations. My Indigenous friends helped me understand the role of sacrament, acknowledging and ritualizing our oneness with all creation, humbling one’s self to the larger living family, and reminding ourselves that “The Mother holds the hammer.”

The magpie

I must have been four years old when my sister, Kaye, two years older, first led me across the canal bridge and into the red foot hills of Big Horn Basin, north of Worland, Wyoming. I didn’t know it then, but this was the home that Crazy Horse, Gall, and Sitting Bull died to retain for their Lakota families, ancestors of my later friends in Pine Ridge.

Kaye and I explored ravines and caves in the dry Palaeozoic siltstone that flashed with crystalline colors in the sun. On the way home, we traversed a ledge to a sandstone crag. My sister slid down but I could not muster the courage nor back up. She instructed me to wait as she ran home to fetch help. I watched her across the dry ground until she became a glint of motion and then disappeared. I felt alone but trusted my sister to bring help.

There, awaiting my rescuers, I leaned against the brittle earth and pondered the nature of rock and dirt. I had never felt so alone. Sunlight glinted off flakes of mica in the coarse, reddish-brown soil. Abruptly, a magpie appeared, looped around the sculptured stone, lit onto an outcrop, and thumped his beak twice in blistering soil. The bird tilted its head and looked directly at me, curiously.

I realize now, looking back, that this was the moment I first felt the wild, natural world looking back at me, as I contemplated it. The magpie — which I now know as the North American Black-winged magpie (Pica hudsonia) — showed no fear, but an inquisitive poise. I remained still, so that the bird would stay. I felt a certain comfort and safety with the bird nearby, no longer alone. It hopped from rock to rock, but always returned, cocked its head, and contemplated me. I felt seen and felt a sort of affinity that I could not have explained then, and find hard to explain now.

I suspect that this was the moment that I first felt a kinship with the wild world, the world not dominated by people, their goals, their enthusiasms, and their presumptions. Formal education can desensitize us, teach us to see through the lens of acumen or ambition. Without having the words, this was the moment I deeply understood “all my relations,” when I felt the meaning of “the patterns that connect,” when sacrament felt natural, and when the instinct to protect all living beings felt innate, part of being alive.

As expected, my sister returned with help.

When I contemplate this now, I realize that Rachel Carson, Gregory Bateson, the burning Cuyahoga River, and the Indigenous elders just reminded me of the lesson of the magpie. All my relations. One heart, one mind, one prayer.

References and links

Rachel Carson: Silent Spring, 1962

The Sea Trilogy: Under the Sea-Wind / The Sea Around Us / The Edge of the Sea

Gregory Bateson: Mind and Nature: Systems, complexity, co-evolution

Film: Ecology of Mind, by daughter Nora Bateson; excellent summary of Bateson’s work.

Steps to an Ecology of Mind: collected essays

Winona LaDuke: All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life

Recovering the Sacred: The Power of Naming and Claiming

G. Sessions, ed: Deep Ecology for the 21st Century: A good collection of deep ecology essays: Arne Naess, Chellis Glendinning, Gary Snyder, Dolores LaChapelle, Paul Shepard, George Sessions, and others.

Arne Naess: The Ecology of Wisdom

David Abram: Spell of the Sensuous

Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology