Add your name now to demand South Africa’s biggest supermarkets ditch throwaway plastic once and for all.

SIGN NOWHow often do you eat takeaway food? What about pre-prepared ready meals? Or maybe just microwaving some leftovers you had in the fridge? In any of these cases, there’s a pretty good chance the container was made out of plastic. Considering that they can be an extremely affordable option, are there any potential downsides we need to be aware of? We decided to investigate this claim.

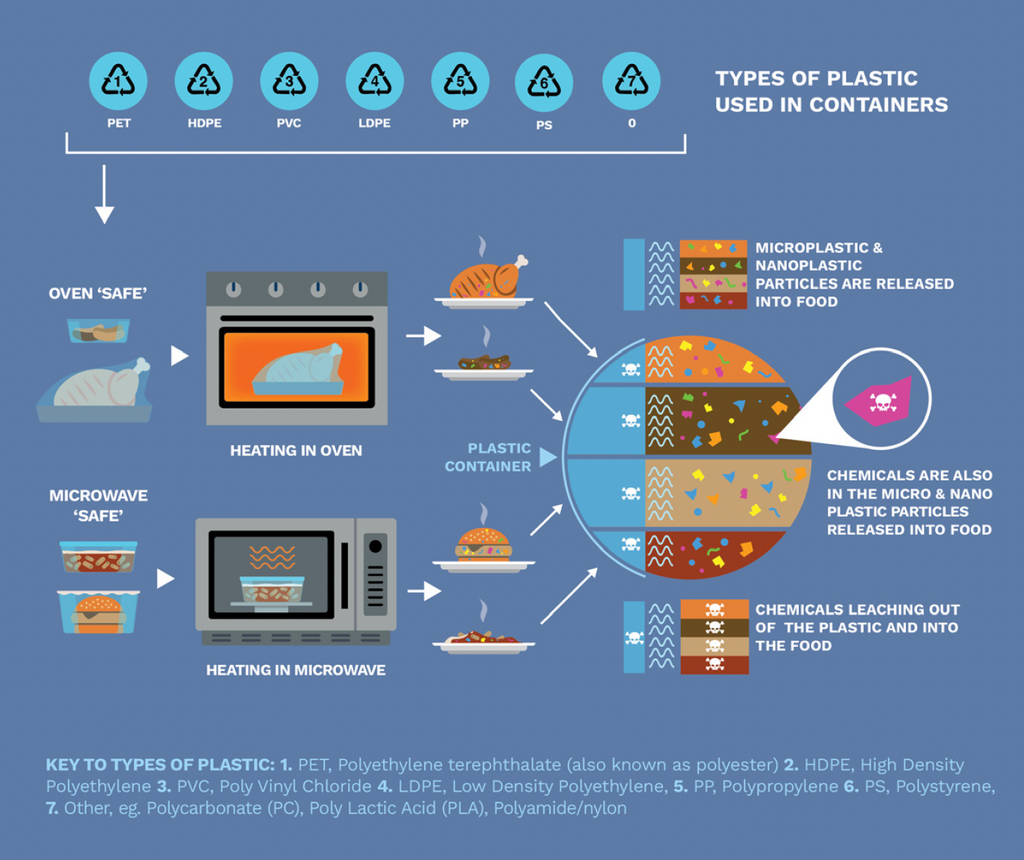

Scientific research increasingly shows that heating food in plastic packaging can release microplastics and plastic chemicals into the food we eat. A new Greenpeace International review of peer-reviewed studies finds that microwaving plastic food containers significantly increases this release, raising concerns about long-term human health impacts. This article summarises what the science says, what remains uncertain, and what needs to change.

There’s no shortage of research showing how microplastics and nanoplastics have made their way throughout the environment, from snowy mountaintops and Arctic ice, into the beetles, slugs, snails and earthworms at the bottom of the food chain. It’s a similar story with humans, with microplastics found in blood, placenta, lungs, liver and plenty of other places. On top of this, there’s some 16,000 chemicals known to be either present or used in plastic, with a bit over a quarter of those chemicals already identified as being of concern. And there are already just under 1,400 chemicals that have been found in people.

Not just food packaging, but plenty of household items either contain or are made from plastic, meaning they potentially could be a source of exposure as well. So if microplastics and chemicals are everywhere (including inside us), how are they getting there? Should we be concerned that a lot of our food is packaged in plastic?

Plastic food packaging: the good, the bad, and the ugly

The growing trend towards ready meals, online shopping and restaurant delivery, and away from home-prepared meals and individual grocery shopping, is happening in every region of the world. Since the first microwaveable TV dinners were introduced in the US in the 1950s to sell off excess stock of turkey meat after Thanksgiving holidays, pre-packaged ready meals have grown hugely in sales. The global market is worth $190bn in 2025, and is expected to reach a total volume of 71.5 million tonnes by 2030. It’s also predicted that the top five global markets for convenience food (China, USA, Japan, Mexico and Russia) will remain relatively unchanged up to 2030, with the most revenue in 2019 generated by the North America region.

A new report from Greenpeace International set out to analyse articles in peer-reviewed, scientific journals to look at what exactly the research has to say about plastic food packaging and food contact plastics.

Here’s what we found.

Our review of 24 recent articles highlights a consistent picture that regulators, businesses and

consumers should be concerned about: when food is packaged in plastic and then microwaved, this significantly increases the risk of both microplastic and chemical release, and that these microplastics and chemicals will leach into the food inside the packaging.

And not just some, but a lot of microplastics and chemicals.

When polystyrene and polypropylene containers filled with water were microwaved after being stored in the fridge or freezer, one study found they released anywhere between 100,000-260,000 microplastic particles, and another found that five minutes of microwave heating could release between 326,000-534,000 particles into food.

Similarly there are a wide range of chemicals that can be and are released when plastic is heated. Across different plastic types, there are estimated to be around 16,000 different chemicals that can either be used or present in plastics, and of these around 4,200 are identified as being hazardous, whilst many others lack any form of identification (hazardous or otherwise) at all.

The research also showed that 1,396 food contact plastic chemicals have been found in humans, several of which are known to be hazardous to human health. At the same time, there are many chemicals for which no research into the long-term effects on human health exists.

Ultimately, we are left with evidence pointing towards increased release of microplastics and plastic chemicals into food from heating, the regular migration of microplastics and chemicals into food, and concerns around what long-term impacts these substances have on human health, which range from uncertain to identified harm.

© William Morris-Julien / Greenpeace

Illustrated diagram showing how heating food in plastic containers releases microplastics, nanoplastics and chemicals into food. The graphic lists common plastic types used in food containers, including PET, HDPE, PVC, LDPE, PP, PS and other plastics. It shows food being heated in ovens and microwaves in containers labelled “oven safe” and “microwave safe”. Arrows lead from heated food to a cutaway of a plastic container filled with coloured particles, representing microplastics, nanoplastics and chemical additives migrating from the plastic into food.

The known unknowns of plastic chemicals and microplastics

The problem here (aside from the fact that plastic chemicals are routinely migrating into our food), is that often we don’t have any clear research or information on what long-term impacts these chemicals have on human health. This is true of both the chemicals deliberately used in plastic production (some of which are absolutely toxic, like antimony which is used to make PET plastic), as well as in what’s called non-intentionally added substances (NIAS).

NIAS refers to chemicals which have been found in plastic, and typically originate as impurities, reaction by-products, or can even form later when meals are heated. One study found that a UV stabiliser plastic additive reacted with potato starch when microwaved to create a previously unknown chemical compound.

We’ve been here before: lessons from tobacco, asbestos and lead

Although none of this sounds particularly great, this is not without precedence. Between what we do and don’t know, waiting for perfect evidence is costly both economically and in terms of human health. With tobacco, asbestos, and lead, a similar story to what we’re seeing now has played out before. After initial evidence suggesting problems and toxicity, lobbyists from these industries pushed back to sow doubt about the scientific validity of the findings, delaying meaningful action. And all the while, between 1950-2000, tobacco alone led to the deaths of around 60 million people. Whilst distinguishing between correlation and causation, and finding proper evidence is certainly important, it’s also important to take preventative action early, rather than wait for more people to be hurt in order to definitively prove the point.

Where to from here?

This is where adopting the precautionary principle comes in. This means shifting the burden of proof away from consumers and everyone else to prove that a product is definitely harmful (e.g. it’s definitely this particular plastic that caused this particular problem), and onto the manufacturer to prove that their product is definitely safe. This is not a new idea, and plenty of examples of this exist already, such as the EU’s REACH regulation, which is centred around the idea of “no data, no market” – manufacturers are obligated to provide data demonstrating the safety of their product in order to be sold.

But as it stands currently, the precautionary principle isn’t applied to plastics. For REACH in particular, plastics are assessed on a risk-based approach, which means that, as the plastic industry itself has pointed out, something can be identified as being extremely hazardous, but is still allowed to be used in production if the leached chemical stays below “safe” levels, despite that for some chemicals a “safe” low dose is either undefined, unknown, or doesn’t exist.

A better path forward

Governments aren’t acting fast enough to reduce our exposure and protect our health. There’s no shortage of things we can do to improve this situation. The most critical one is to make and consume less plastic. This is a global problem that requires a strong Global Plastics Treaty that reduces global plastic production by at least 75% by 2040 and eliminates harmful plastics and chemicals. And it’s time that corporations take this growing threat to their customers’ health seriously, starting with their food packaging and food contact products. Here are a number of specific actions policymakers and companies can take, and helpful hints for consumers.

Policymakers & companies

- Implement the precautionary principle:

- For policymakers – Stop the use of hazardous plastics and chemicals, on the basis of their intrinsic risk, rather than an assessment of “safe” levels of exposure.

- For companies – Commit to ensure that there is a “zero release” of microplastics and hazardous chemicals from packaging into food, alongside an Action Plan with milestones to achieve this by 2035

- Stop giving false assurances to consumers about “microwave safe” containers

- Stop the use of single-use and plastic packaging, and implement policies and incentives to foster the uptake of reuse systems and non-toxic packaging alternatives.

Consumers

- Encourage your local supermarkets and shops to shift away from plastic where possible

- Avoid using plastic containers when heating/reheating food

- Use non-plastic refill containers

Trying to dodge plastic can be exhausting. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, you’re not alone. We can only do so much in this broken plastic-obsessed system. Plastic producers and polluters need to be held accountable, and governments need to act faster to protect the health of people and the planet. We urgently need global governments to accelerate a justice-centred transition to a healthier, reuse-based, zero-waste future. Ensure your government doesn’t waste this once-in-a-generation opportunity to end the age of plastic.

Trying to dodge plastic can be exhausting. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, you’re not alone. We can only do so much in this broken plastic-obsessed system. Plastic producers and polluters need to be held accountable, and governments need to act faster to protect the health of people and the planet. We urgently need global governments to accelerate a justice-centred transition to a healthier, reuse-based, zero-waste future. Ensure your government doesn’t waste this once-in-a-generation opportunity to end the age of plastic.

Add your name now to demand South Africa’s biggest supermarkets ditch throwaway plastic once and for all.

SIGN NOW