The story of a small-scale farmer named Francis Ngiri, who has been farming for over 20 years in Makongo, a village in Kenya, exemplified the devastating effects of the capitalist farming practices of multinational corporations in Africa. In his youth, Francis learned the time-tested practice of seed saving from his father, who also learned it from his father. Indigenous seeds, adapted over generations to local climates and soils, are more resilient to pests, diseases, and extreme weather conditions. These seeds are integral to agricultural biodiversity, providing a diverse genetic pool vital for the resilience of community food systems.

However, over the years, small-scale farmers like Francis were enticed by the promises of quick fixes offered by industrial agriculture. The allure of quick and higher yields led Francis away from the traditional practices passed down through generations. He began using certified seeds and toxic chemicals, leaving behind the indigenous seeds that had sustained his family and community for generations.

Fast forward to 2015 when I first met Francis at a Seed Saving Training in Kenya. Fresh out of the university I was eager to start my career and support small-scale farmers. My first conversation with Francis revealed a very tired man who was almost giving up. At that time, Francis was a contract farmer for a multinational corporation. He and other farmers planted chickpeas and finger millet seeds provided by the multinational and would sell them back to them after harvesting. To be able to farm actively with the multinational, they had to take a loan to buy more farm inputs and also formed a community-based organization called the Makongo CBO.

However, the El Niño rains came and devastated everything they had planted. When their crops were destroyed and they were left with nothing, the multinational ran for the hills, leaving them to deal with all the damage and loss alone. Left with nothing and a loan to repay, they sought help from the government. When I met Francis during the training, he looked frail and sad, worn out by the impacts of the disaster. During this time, the Seed Savers Network Kenya had begun campaigns in their area, advocating the importance of indigenous seed saving for sufficiency, food security, biodiversity, and climate change resilience. Francis and his fellow farmers joined this movement, initially collecting and saving just ten varieties of seeds in their seed bank. Today, the Makongo Farmers Network boasts over one hundred seed varieties.

Since establishing their seed bank, they now always have seeds available, even after extreme weather events. This traditional practice has restored the independence of some of the local farmers, strengthened their livelihoods, and ensured food security. Community seed saving and sustainable farming have proven crucial for Francis and his community. By maintaining a diverse seed bank, they also preserve agricultural biodiversity, which is vital for resilient ecosystems. Additionally, sustainable farming practices, rooted in local knowledge and tradition, have improved soil health and productivity, reducing the need for costly toxic chemical inputs.

But you know what? The act of sharing and exchanging indigenous seeds among local farmers themselves is illegal in Kenya and many other countries across Africa, including Ghana, Mozambique, Malawi, South Africa and Zimbabwe just to mention a few.

But what happens when this age-old practice is threatened?

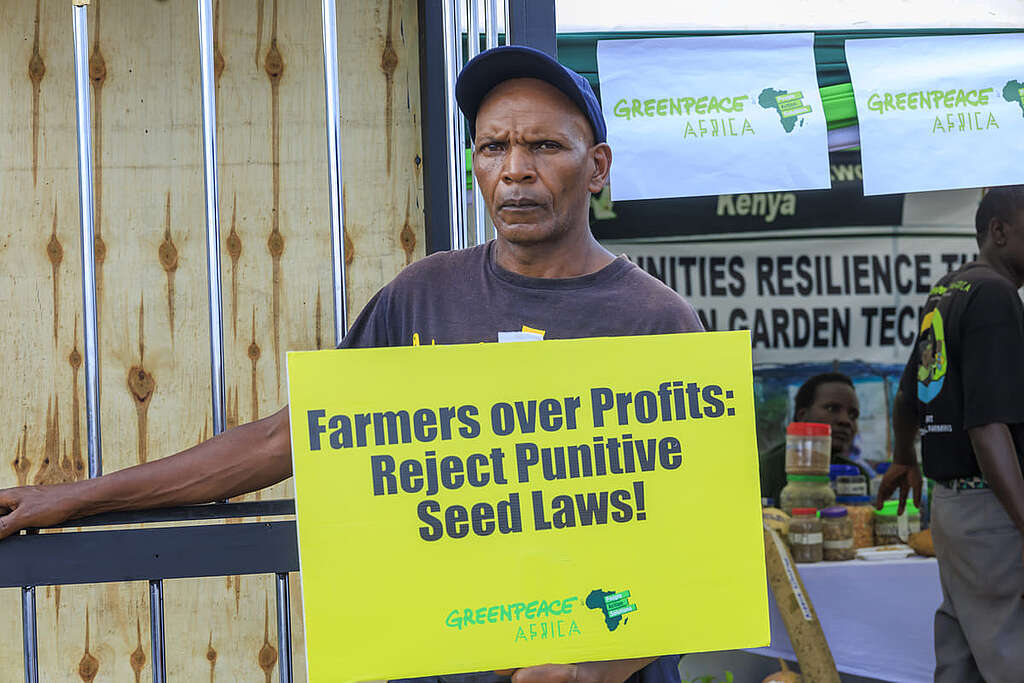

Across Africa, governments have been enacting draconian seed laws that criminalize the exchange and sale of uncertified seeds. These laws, often influenced by corporate interests, impose harsh penalties on farmers who dare to save and share their seeds. Certified seeds, which take away the independence of local farmers, usually come with specific pesticides and fertilizers, trapping farmers in a cycle of debt as they must purchase these inputs every season. These toxic pesticides are not only harming human beings but also our environment, contaminating soil and water, killing beneficial insects, and disrupting ecosystems. Such regulations are direct assaults on the traditional practices and livelihoods of smallholder farmers like Francis.

Do we really want a future where Africa’s food systems are controlled by a handful of corporations?

The importance of indigenous seeds to biodiversity cannot be overstated. Biodiversity is the backbone of resilient ecosystems. The loss of diverse seed varieties means the loss of genetic resources that could be vital in adapting to changing environmental conditions. The loss also leads to monocultures that are vulnerable to pests and diseases, increasing the risk of food insecurity. Francis remembers the time when his village’s fields were a patchwork of different crops and varieties, each with its unique traits and strengths. But now, as monocultures take over, that diversity is vanishing.

Already, we have lost a staggering amount of our agricultural biodiversity. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 75% of the world’s crop diversity was lost between 1900 and 2000. This alarming trend is accelerating, driven by industrial agriculture and the aggressive promotion of uniform, corporate-controlled seed varieties. The consequences of this loss are dire.

Why should a farmer in rural Africa be forced to buy seeds from a multinational corporation headquartered thousands of miles away?

We must take back the power and the right over our food systems from corporations that prioritize profit over people. These multinational corporations are systematically eroding the rich agricultural heritage that has sustained communities for generations. It is time to challenge this corporate dominance and reaffirm the rights of farmers to save, use, exchange, and sell their seeds. We need to advocate for policies that protect and promote farmer-managed seed systems. Therefore, we must resist punitive seed laws and demand their repeal. It is crucial to support local and indigenous seed networks, recognizing them as vital to food security and biodiversity. Governments should invest in agricultural research that benefits smallholder farmers rather than catering to the interests of large agribusinesses.

Today as we celebrate International Day for Biological Diversity, we call upon all stakeholders—farmers, policymakers, activists, and consumers—to unite in the protection of farmer-managed seed systems. We must ensure that the power over our food systems remains in the hands of those who feed us: the farmers. The time to act is now. Our seeds, our food, our heritage, and our future depend on it.

An outrageous law stops smallholder farmers in Kenya from using indigenous seeds to exchange them with other farmers – an age-old tradition.

SIGN THE PETITION