When it comes to double standards between the “Global North” and the “Global South,” is it ever really a surprise? From waste colonialism to environmental racism, Africa has long been treated as the dumping ground for what the West no longer wants. So, it’s hardly a shock that pesticides deemed “too toxic” for use in Europe are still making their way to our farms and markets.

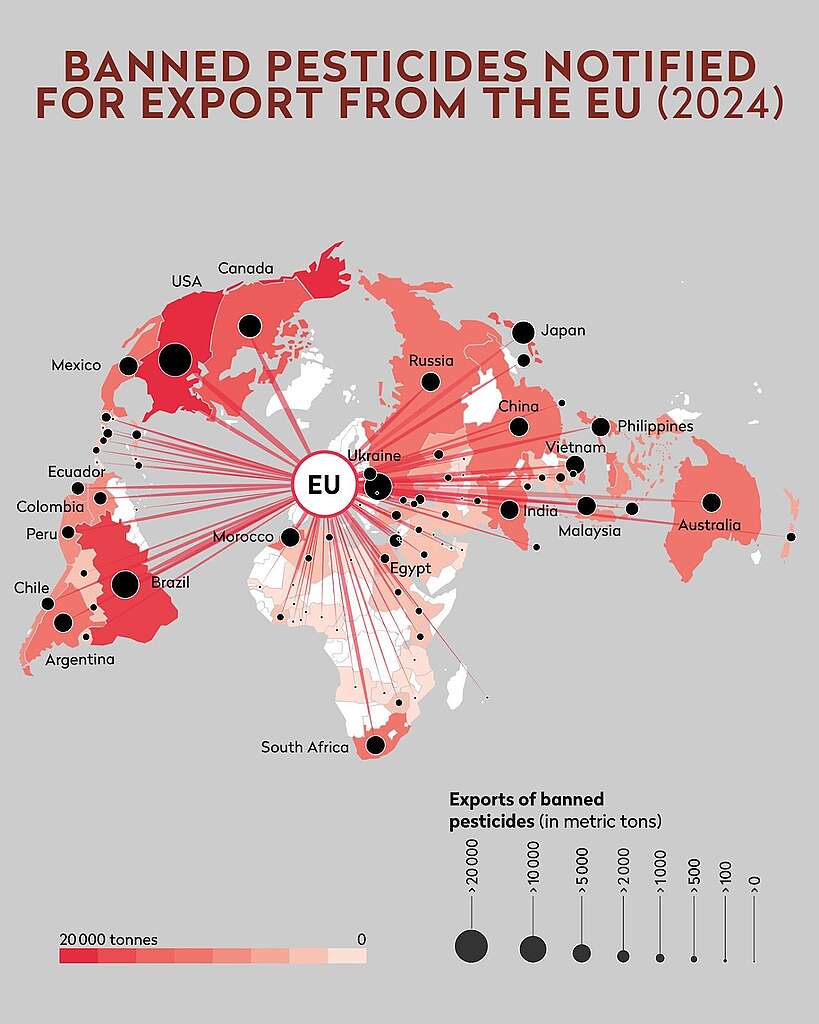

A recent investigation by Unearthed and Public Eye exposed that 44 Highly Hazardous Pesticides (HHPs) banned in the EU are still being shipped for use on the African continent. In 2024 alone, the EU planned to export nearly 9,000 tonnes of these toxic pesticides to Africa.

But if they are illegal to use in Europe for being “too toxic” for human health or the environment, how can they still be good enough to send to Africa?

According to documents obtained under freedom of information laws, these banned pesticides are being sent to countries like South Africa, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Sudan, Morocco, and Tunisia – coming from several European countries, the top 5 being Germany, Spain, Italy, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

Banned in Europe, exported to Africa

First on the list of pesticides banned in Europe but still exported to Africa is cyanamide, which was banned in the EU nearly 20 years ago for showing “clear indications” of being harmful to the health of farm workers.

A list of fungicides illegal in the EU are also being shipped to Africa. One of them is Chlorothalonil, which was banned in the EU in 2019 and required to be phased out in all EU member states by 2020, for being a groundwater contaminant and a “presumed human carcinogen.” Others like Epoxiconazole and Mancozeb, banned in 2020 and 2021 respectively after being classified as harmful to fertility and babies in the womb, are still being dumped on Africa’s doorstep.

Also notified for export by EU companies is a particularly toxic bee-killing neonicotinoid called “Thiamethoxam,” which was banned from all outdoor use in the EU in 2018.

Far more disturbing is that the “soil fumigant” 1,3-dichloropropene (1,3-D), a pesticide that’s been banned since 2007 due to concerns about groundwater contamination and risks to wildlife, was the EU’s biggest banned pesticide export to Africa, by weight in 2018. For emphasis, EU-based companies notified export of around 3,600 tonnes of this pesticide to Africa, with South Africa, Kenya, and Morocco as the main destinations.

Last year, Morocco, South Africa, Egypt, Tunisia, and Kenya were among the 25 African countries to which the EU notified exports of banned pesticides.

The loopholes that keep toxic chemicals flowing

Two words – “Export Notifications”. For context, companies can’t usually ship banned pesticides out of the EU without the “prior informed consent” of the importing country’s government. This means that our governments are complicit because they are signing this off.

Whether through weak regulation, outdated laws, or sheer political pressure, many governments across the continent continue to approve chemicals that have been banned elsewhere for being too dangerous. Some don’t have the capacity to thoroughly assess the risks. Others may be swayed by powerful agrochemical lobbies, trade deals, or the promise of short-term agricultural gains.

The question we can’t ignore: why do African farmers keep spraying the “poison”?

The answer is layered, painful, and rooted in survival and systemic failures. At the most basic level, there is a lack of awareness and information. Labels are often written in languages they can not read or filled with scientific jargon/ instructions that makes them impossible to interpret.

In Tanzania, more than half of surveyed farmers admitted to storing pesticides in their homes or reusing containers unsafely – pointing to deep gaps in extension and safety support – as well as weak regulations that still allow banned products on shelves.

On top of this, there is the crushing reality of economic dependence. For smallholder farmers living harvest to harvest, pesticides are marketed as lifelines; cheap, accessible, and offering quick fixes.

Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa shows many farmers spray pesticides prophylactically, because they view chemicals as a form of “insurance”. This dependence is deepened by agricultural systems shaped by the Green Revolution model, and credit or subsidy programs from governments and donors, which pair hybrid seeds with fertilizers and pesticides.

The problem is also linked to climate change and resilience. Aggressive marketing by agrochemical companies frames pesticides as modern and essential for productivity in the face of the current climate crisis. Rising temperatures and erratic rainfall are increasing pest outbreaks, making farmers even more reliant on fast, chemical fixes to protect their crops. With the promise of short-term gains, HHPs have created the perception that they are essential for food production.

And while farmers carry the burden of exposure in the fields, consumers carry it on their plates, eating food every day without knowing that it has been grown with substances considered too toxic for Europe – while leaving behind a trail of human-health risks like cancer, biodiversity loss, degraded soils and polluted waters.

Alternatives to pesticides. What are the solutions?

Across Africa, farmers and researchers are already experimenting with safer, more sustainable methods. Case studies from Kenya show that viable options are working on the ground, though barriers of training, market access, and government support still remain. There is no single silver bullet, but integrated approaches blending traditional knowledge with modern science are proving effective.

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is increasingly recognized as a system that reduces reliance on pesticides by combining safer, cheaper, and more sustainable methods. The first part of the system is regular monitoring, where farmers check their crops to see which pests are present and whether they’ve reached harmful levels.

Secondly, prevention is emphasized through good practices such as crop rotation, intercropping, and building healthy soils that make plants stronger and less attractive to pests. Additionally, the system relies on biological allies like ladybirds, birds, or fungi that naturally attack pests and help nature do the work. In Kenya, the wasp Acerophagus papayae has helped tackle the papaya mealybug.

Lastly, only when absolutely necessary, pesticides are applied carefully and minimally, choosing the right product, in the right amount, at the right time.

Biopesticides offer another path by working with nature instead of against it. Biopesticides made from plants, microbes, or minerals, are also gaining ground – neem sprays in Ghana are reducing reliance on synthetic chemicals. These methods leave little or no harmful residue, protect pollinators, and are vital for export crops that must meet strict residue limits.

However, access remains a major issue across the continent – safe biopesticides and biologicals are not always available locally or are priced out of reach for smallholder farmers. Agroecology is not just about one tool, but about balancing crops, soils, insects, and farmer knowledge in harmony.

What must change: policy justice for African farmers

To dismantle this toxic double standard, Greenpeace Africa calls for:

- A total ban on the export of pesticides already banned in the EU

- African governments to refuse export notifications and update import regulations

- Public disclosure of pesticide import data and accountability of companies involved

- Investment in agroecological training, farmer field schools and local biopesticide production

- Stronger protection measures for farmworkers and consumers, backed by law

In conclusion, Africa doesn’t need hand-me-down chemicals; the future of our agriculture lies not in toxic imports, but in the power to choose what we grow – safely, sustainably, and on our own terms. It’s time we stop importing poison and start cultivating solutions that grow from our own soil.