For the last decade the Dja’s biodiversity has been under severe pressure. Threats identified by UNESCO include wildlife poaching, the construction of the Mékin hydroelectric dam north of its boundaries, the prospect of a nickel-cobalt mining project currently owned by Geovic to the East, and, above all, the development of the giant Sud-Cameroun Hevea (Sudcam) rubber plantation as close as a few hundred meters from its western border. (1)

In late 2015, UNESCO and the IUCN conducted a joint field mission to monitor the impacts of these threats on the Dja. Its report explains in detail the serious negative impacts of each of these pressures, but inexplicably, lists only the Mékin dam and poaching as “Ascertained Dangers” to the reserve’s “Outstanding Universal Value”.

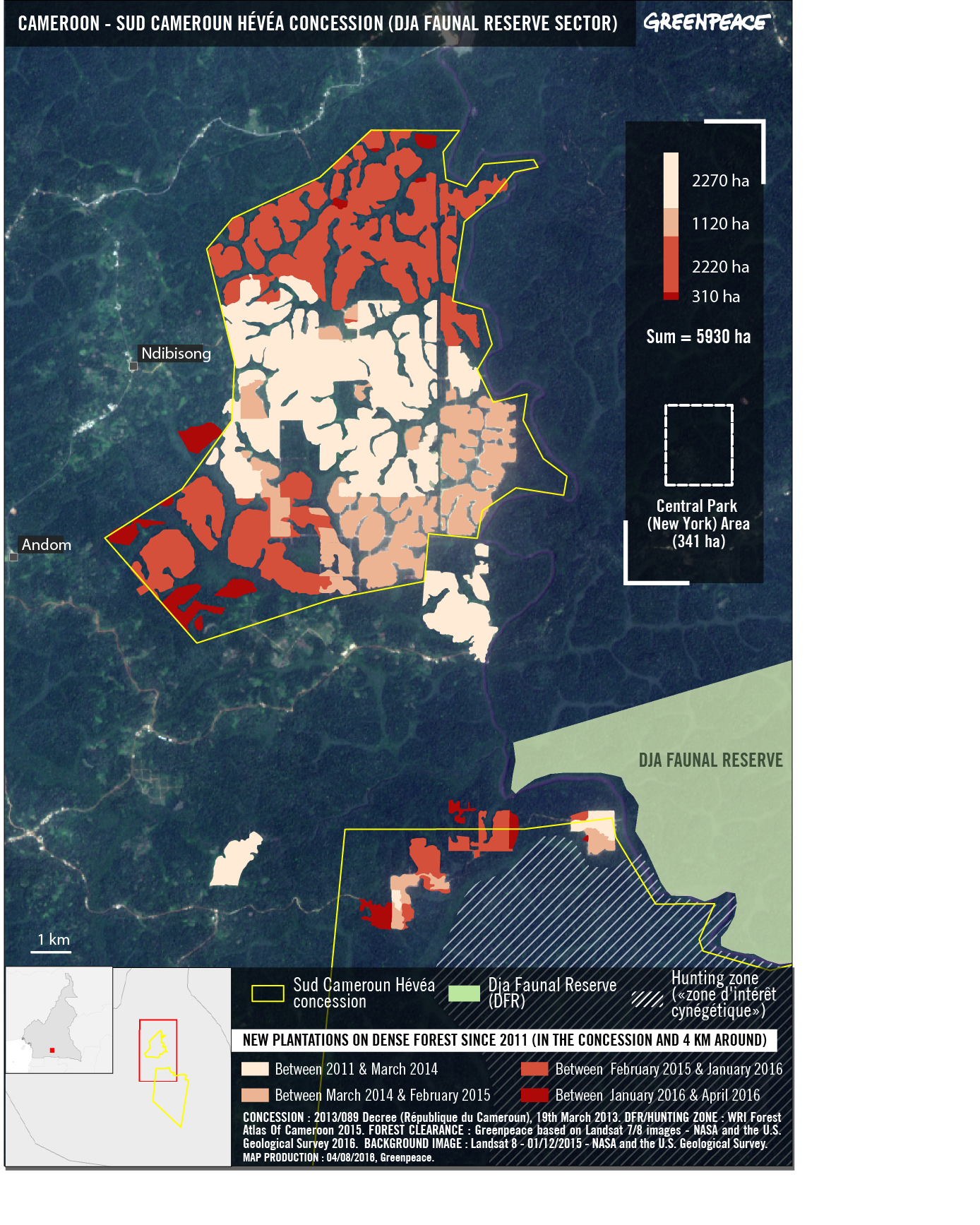

Last July 7 Greenpeace wrote to the UNESCO World Heritage Committee to express our alarm about the lack of attention paid to the threat created by the Sudcam plantation. A recent Greenpeace analysis of satellite images shows that since 2011 the company has clear-cut 5,930 ha of forest, 42 % of it over the past one and a half year. That’s over 5,000 ha more than the clearing at the SGSOC palm oil plantation in Cameroon’s South West Region, a project which has been the object of massive NGO and media scrutiny since 2010.

Sudcam was established in 2010 as a joint venture company between the Singapore-based GMG Global Ltd (GMG), a subsidiary of the Chinese state-owned company Sinochem (80% of the shares) and the Société de Productions de Palmeraies et d’Hévéa (SPPH) (20% of the shares). (2)

The Sudcam plantation is located only kilometers from the Mvomeka’a mansion and security compound of the Cameroonian president, Paul Biya. In a paper published last year, researchers from the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) wrote that “[the] allocation of a temporary concession to Sud-Cameroun Hevea SA without taking into account the criteria specified in land regulations seems to have been motivated by the personality behind the Cameroonian who holds 20% of the company’s share.” They added “According to a local representative of the Ministry of the Environment, the President of the Republic’s family owns the company. However we have learned only that an influential member of the Cameroonian political elite, whose identity we do not know, apparently owns 20% of the company’s shares.” (3)

Sinochem and the Singapore-based rubber company Halcyon Agri Corp – one of the top five largest natural rubber suppliers globally – are currently in the process of merging their rubber operations. (4) In its annual reports GMG claims that the 45,198 ha it was awarded in April 2013 is a freehold. (5) Yet, Greenpeace understands that Cameroonian law does not provide for freehold allotment of national lands, and then wonders why GMG uses this term in an official publication. (6)

The opacity and questionable legality of the Sudcam project – by far the Congo Basin’s most devastating new clearing of forest for agriculture – has been encouraged by donors’, media’s and NGOs’ near total indifference to it. (7) Yet this has apparently not stopped the French publicly funded research institute Centre International en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement (CIRAD) from providing technical advice to the plantation, as part of what GMG’s CEO calls a “long-term collaboration”. (8) (The current CEO of GMG International SA, CEO of Sudcam from 2010 to 2014, is French.) And, for its part, the European Union Delegation in Cameroon has been a key cheerleader: in an official June 2013 report the EU-financed Independent Observer of Forestry Control recommended that the company continue clearing 11,300 ha (on land it is likely illegally occupying). (9)

Greenpeace also deplores the unbelievably racist and neocolonial language used by Sinochem to describe its project in Cameroon. In one English language release, published under the heading “Employee’s Stories”, one can read:

“Local staff felt inspired to work hard with their Chinese partners as a united team for a shared goal. This was really in great contrast to the casual working attitude widely seen in Cameroon, a country that mainly depends on the mercy of nature for living.”

The author describes the project area as a “wasteland overgrown with weeds”, adding:

“In spite of shortage in machines and staff, the former barren scenes were quickly taken over by lush and endless nursery garden of rubber seedlings lined in great order after more than one year of painstaking efforts by such pioneers. Such extraordinary development speed totally astonished and convinced Cameroon government. “Only your pioneering squad from China could create such a magic – to blaze a road of hope among the bleak wilds.”

The border of the Dja Reserve is certainly not an overgrown wasteland, but a forest of major biodiversity and the traditional land of local communities. Rainforest Foundation UK has been conducting participatory mapping with local communities inside and around the rubber concession. Cameroonians depend on the land and forest Sudcam is converting to industrial rubber for fishing, hunting, gathering, and farming. According to Rainforest Foundation UK “[The] communities have decried very poor or non-existent consultation by the company, the subsequent clearing of thousands of hectares of forest and demolishing of settlements, graves and farms. Communities say there has been wholly inadequate compensation, provisions to protect their livelihood, and no benefits from the plantations.

On 14 July 2016, the UNESCO World Heritage Committee was asked to vote on a draft decision to inscribe the Dja on the List of World Heritage in Danger. (10) Unfortunately, only Finland voted in favor while all other delegations opposed the measure. You can click here to watch the “debate.” (11)

As in many other cases of agribusiness development in the Congo Basin, land acquisition for the Sudcam plantation is surrounded by opacity. Key information about the project, such as the full set of concession limits, land rent paid, ownership information, effective investment realized so far are not in the public domain, making it hard for anyone to assess legality and impacts and hold government and companies accountable.

Greenpeace calls upon the Cameroonian government to suspend Sudcam’s lease agreements until clear preconditions and modalities are established, including adequate planning for participatory national land use planning and a due, transparent process to ensure free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of the local communities. Sudcam should immediately halt the conversion of forests inside its concessions and conduct a new environmental impact assessment.

In the absence of transparency from the authorities and the company, Greenpeace is publishing a series of documents concerning Sudcam which should be in the public domain.

- Establishment Convention between the Cameroon Government and Sud Cameroun Hévéa;

- Sudcam’s Environmental Impact Assessment;

- Sudcam’s provisional land lease of 2008;

- Sudcam’s freehold land concession of 2013;

- Sudcam’s second provisional land lease of 2015;

- Miscellaneous documents related to Sudcam’s activities:

(1) UNESCO. 2016. Rapport de la mission de suivi réactif conjointe UNESCO/UICN à la Réserve de Faune du Dja, République du Cameroun, 28 novembre-05 décembre 2015. Available at: http://whc.unesco.org/document/141993

(2) GMG Global Ltd. 2010. Establishment of Joint Venture Company.

(3) Samuel Assembe-Mvondo, Louis Putzel, Richard Eba’a Atyi, 2015. Socioecological responsibility and Chinese overseas investments. The case of rubber plantation expansion in Cameroon. CIFOR Working Paper no. 176. Available at: http://www.cifor.org/library/5474/socioecological-responsibility-and-chinese-overseas-investments-the-case-of-rubber-plantation-expansion-in-cameroon/

(4) See: www.halcyonagri.com

(5) GMG Global Ltd, Annual Report 2013, http://gmg.listedcompany.com/misc/ar2013.pdf, p.122.

(6) Decree No. 76-166 of 17April 1976 to establish the terms and conditions of management of national lands. See §1 and §10(3).

(7) Greenpeace wrote a letter to Sudcam in 2014 requesting basic information about the project, but received no response. Letter available at: http://www.greenpeace.org/international/Global/international/briefings/forests/2014/congo/Sud-Cameroun-Hevea-Letter.pdf

(8) GMG Global Ltd. 2016. op. cit., pp. 10-11.

(9) « Dénonciation Meyomessala » in AGRECO. 2013. Rapport Technique n°7 du 1er janvier au 30 juin 2013, pp. 30-32.

(10) See UNESCO Report 40 COM WHC/16/40.COM/7B. Item 7B of the Provisional Agenda: State of conservation of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List. Pages 143-146. http://whc.unesco.org/archive/2016/whc16-40com-7B-en.pdf