Even the seemingly mundane feces of animals unveil a concerning reality of plastic pollution in Hong Kong. In collaboration with research teams from universities in Hong Kong and Taipei, Greenpeace has released the first-ever “Study on Microplastics in the Feces of Countryside Mammals” in Hong Kong. The study found microplastics in the feces of five common wild mammal species — buffalo, cattle, porcupine, boar, and macaque. Out of the 100 samples collected, 85% discovered microplastic with a total of 2,503 particles, signalling a significant problem of microplastic ingestion among countryside animals.

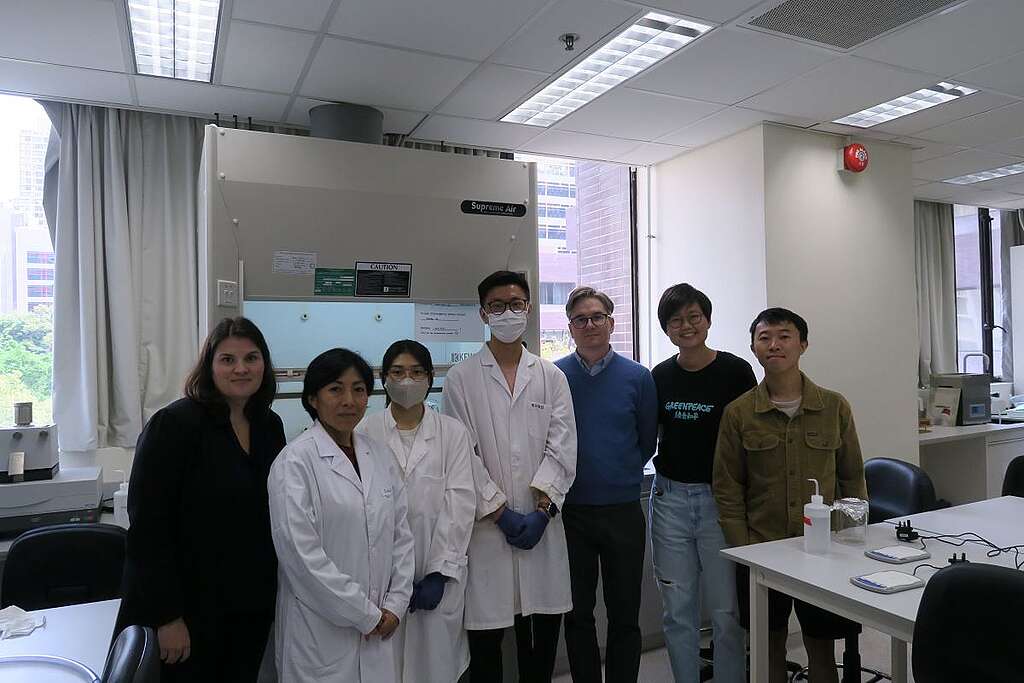

The study lasted two years, and we are grateful for the contribution from universities in Hong Kong and Taiwan in conducting this research, which scientifically documented the harms of plastic pollution. The Greenpeace research team was responsible for sampling and coordinating the collaborative project. Mariella Siña, a PhD student at National Taiwan University, developed the methodology, conducted the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper for scientific publication. NSTC research scholar Dr. Alexander Kunz from the Research Center of Environmental Changes in Academia Sinica provided advice, while Dr. Christelle Not from the University of Hong Kong offered methodological and laboratory support, aided by students Johnny So, Horace Lo, and Carol Kwok in the experimental process.

-2-1024x683.jpg)

Both Christelle and Alexander were deeply impressed by the proximity of urban and rural areas in Hong Kong. However, they expressed concerns about the alarming rise of “plastic goes wild” in the countryside. They hope this research finding will encourage the government, businesses, and the public to act — by reducing plastic use in daily life and advocating for the Global Plastic Treaty at the critical meeting set for the end of 2024.

Globally Rare Research on Terrestrial Microplastics

“Seven or eight years ago, Hongkongers began noticing the unusual spread of plastic — whether at the beach or on a ferry, plastic waste was everywhere… something had clearly gone wrong,” recalled Christelle in her university lab, reminding us of Hong Kong’s rapid journey from awareness to action on plastic pollution. Pivotal moments, like the 2012 “Hong Kong Plastic Disaster” when Typhoon Vicente spilled six containers carrying 150 tons of polypropylene pellets into the sea, and Greenpeace’s 2016 campaign pushing Watsons and 759 Store to phase out microbead products, marked significant milestones that sparked public awareness, and inspired Christelle to integrate these issues into her environmental science curriculum and pursue related research.

In 2018, Christelle published a study revealing that over 60% of seawater samples in Hong Kong contained microbeads. “Even after wastewater treatment, a substantial amount of microbeads reaches the ocean, indicating the scale of our plastic impact.” This study led to the Hong Kong government’s voluntary “Bye Bye Microbeads Charter”, though unlike other places, Hong Kong has yet to enact legislation on microbeads. Christelle also authored papers showing that foam pollution along Asian coastlines is notably more severe than in other regions.

Despite recent microplastic research in Hong Kong, including the first survey on microplastic quantity in Hong Kong countryside streams conducted by Greenpeace in 2021, this new research on animal feces holds significant promise. Christelle noted that the global academic community still lacks a substantial understanding of microplastics; more importantly, past research has largely focused on marine environments, leaving a gap in knowledge about the impact of microplastics on land-based mammals.

“If we are willing to address and tackle pollution at its source on land, we can protect mammals and cut down on plastics reaching the ocean — a win-win solution.”

-1-1024x683.jpg)

“Our Impact is Crucial”

The study focused on common Hong Kong wildlife — buffalo, cattle, porcupine, boar, and macaque. Christelle hoped the findings remind the public that Hong Kong’s rich biodiversity is worth protecting and needs our care. “Few places offer the unique blend of nature and city life as Hong Kong does, which makes it even more important to understand how every action impacts the wilderness.”

Plastic pollution may seem inescapable, as if we are “doomed” to accept it. Christelle once challenged her students to go plastic-free for a month, predicting they would struggle. “Maybe you’ll slip up with a bottled drink or forget to skip the straw in your iced drink. But each time you avoid a piece of single-use plastic, you’ve already made a difference. Every small step counts toward change.”

Prompting Reflection Among Decision-Makers

Alexander, who supported Greenpeace Taiwan in their 2021 report “Plastic Island – A Study on Microplastic Pollution on Protected Animals in TW and Their Habitat”, also joined this study in Hong Kong. With a background in geology, he once discovered polystyrene buried 50-80 cm deep on a beach, which inspired him to investigate the microplastic pollution in 2015, as plastic research was then limited in Taiwan. Later, he included other areas into his research, such as rivers.

-1-1024x576.jpg)

Despite his experience with Taiwan’s research, Alexander noted key environmental differences between the regions. “Taipei is a major city, but head into Taiwan’s mountainous regions, and you’ll find true wilderness, whereas Hong Kong is much more densely populated.” He also explained the challenges of identifying microplastics from animal feces, as the particles are minuscule, making it difficult to differentiate types like polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP), which are commonly found in disposable plastic packaging and tableware.

After publishing the report “Plastic Island”, Alexander was pleasantly surprised by the immediate response from Yushan National Park Headquarters, which implemented policies to stop selling bottled water and using disposable utensils. He remarked, “It usually takes time to persuade decision-makers after publishing research, so I’m glad we could bring about immediate change.” Although he did not expect a similar outcome this time, he hoped this study would inspire decision-makers to reflect on their actions. “Once they learn about the research findings, they might realize, ‘Oh, plastic has infiltrated our daily lives and environment.’ and be motivated to act.”

The completion of “Study on Microplastics in the Feces of Mammals in the Countryside” owes special thanks to doctoral student Mariella Siña, who performed the research, and to HKU students Johnny So, Horace Lo, and Carol Kwok for their support with sample treatment for identification of microplastics.