South Africa has a dominant commercial seed industry, which is primarily geared towards serving the needs of large-scale commercial farmers, with a dominant focus on hybrid, and genetically modified seeds sold mostly by Monsanto operating in South Africa.

South Africa’s marginal small-scale farmers also rely on these commercial seeds as a significant source of planting material, especially for maize.

The culprit? Multinational corporations that dominate the seed industry like Sakata, Syngenta, and most importantly Bayer- Monsanto.

A profile of Monsanto’s Operations in South Africa

Up until the 70s, Monsanto was in the business of supplying toxic, deadly concoctions to the US military duri ftng their imperialist endeavors from agent orange and DTT. This happened between 1962 and 1971.

These mixtures were primarily brewed up for war but when peace rolled around Monsanto found a new market for its chemicals: the agricultural industry. They transformed their weapons of war into herbicides and pesticides.

Monsanto-Bayer is a pioneer of genetic modification of crops and the largest maize seed company in South Africa by sales. It has been operating in South Africa since 1968 and has licensed its genetic modification technology to other seed companies operating in the domestic market. In the late 1990s, it purchased domestic seed companies Sensako and Carnia, thereby taking up a major stake in local seed and grain markets.

Monsanto controls a huge chunk of the South African maize market. It has an even stronger hold over the market in GM maize seed and controls a majority of the country’s commercial glyphosate market.

This then makes South Africa the ninth-largest producer of genetically modified crops in the world, planting genetically modified maize, cotton, and soya.

Destroying the ecosphere for profit

For years Monsanto’s number one tool for waging war on our soil was glyphosate but you probably know it by a more familiar name Roundup. Roundup is marketed as a systemic weed killer but experts say that:

- It impacts the health of the soil by damaging the presence of some beneficial microbes in the soil reducing soil fertility in the long run and representing a serious threat to food security.

- It Kills beneficial plants like milkweed which is the primary nesting foliage for Monarch butterflies.

- It leads to the production of superweeds.

- Glyphosate has also been deemed a probable carcinogen by WHO with one analysis asserting that long-term exposure to roundup increases your chances of contracting non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a type of cancer, by 41%

Bayer, the company that bought Monsanto, is still allowed to sell Roundup despite overwhelming evidence of the harm it causes as the company CEO continues to repeat that glyphosate is safe to use.

Resisting corporate seed laws in South Africa

The best way to achieve corporate control over seeds is to push governments to introduce new seed laws. These include intellectual property laws and seed trade regulations, both measures to privatize seed production and ban non-registered farmers’ seeds.

On 22nd May 2018, South Africa’s corporate seed bills were approved by the Parliamentary Select Committee, after a lengthy review process.

The Seed Bills are the Plant Breeders Rights Bill and the Plant Improvement Bill. Taken together, both seed laws undermine farmer-managed seed systems and prohibit the age-old practices of recycling, exchanging, and selling farm-saved seed.

Instead of embedding the transformative and empowering policies required by the country, they fail to concretely protect and promote smallholder farmers, and small-scale seed enterprises and support social justice and ecological integrity.

As these laws now stand, farmers – or black- or women-owned small seed enterprises wanting to produce seed commercially, will have to comply with onerous and prohibitively costly requirements on the same footing as multinational seed companies.

Further, if farmers recycle and share popular open-pollinated varieties (OPVs) that are protected in the law, they are liable to prosecution, unless they are producing for private and non-commercial purposes only, i.e. on their own holdings and for the sole use of the household.

The Genetically Modified Organisms Act passed in 1997 is another seed law that does little to ensure biosafety. In effect, it opened the door to the import and release of GM seed and enabled GM seed experimentation and bulking in South Africa.

Instead of a strict impartial assessment of applications by the gene companies, the act allows for self-regulated risk assessments to be submitted to the regulator based entirely on in-house tests conducted by the GMO-purveying corporates themselves.

Seed security and sovereignty

Ecological Farming Practices in Three Counties in Kenya

If farmers do not have their own seeds or access to open-pollinated varieties that they can save, improve, and exchange, they have no seed sovereignty – and consequently no food sovereignty – Vandana Shiva

As long as agriculture has existed, farmers have selected and saved healthy seeds for the next season and bred new varieties that ensure the conservation of agricultural biodiversity. Traditionally, women carry(ied) out the important task of seed selection.

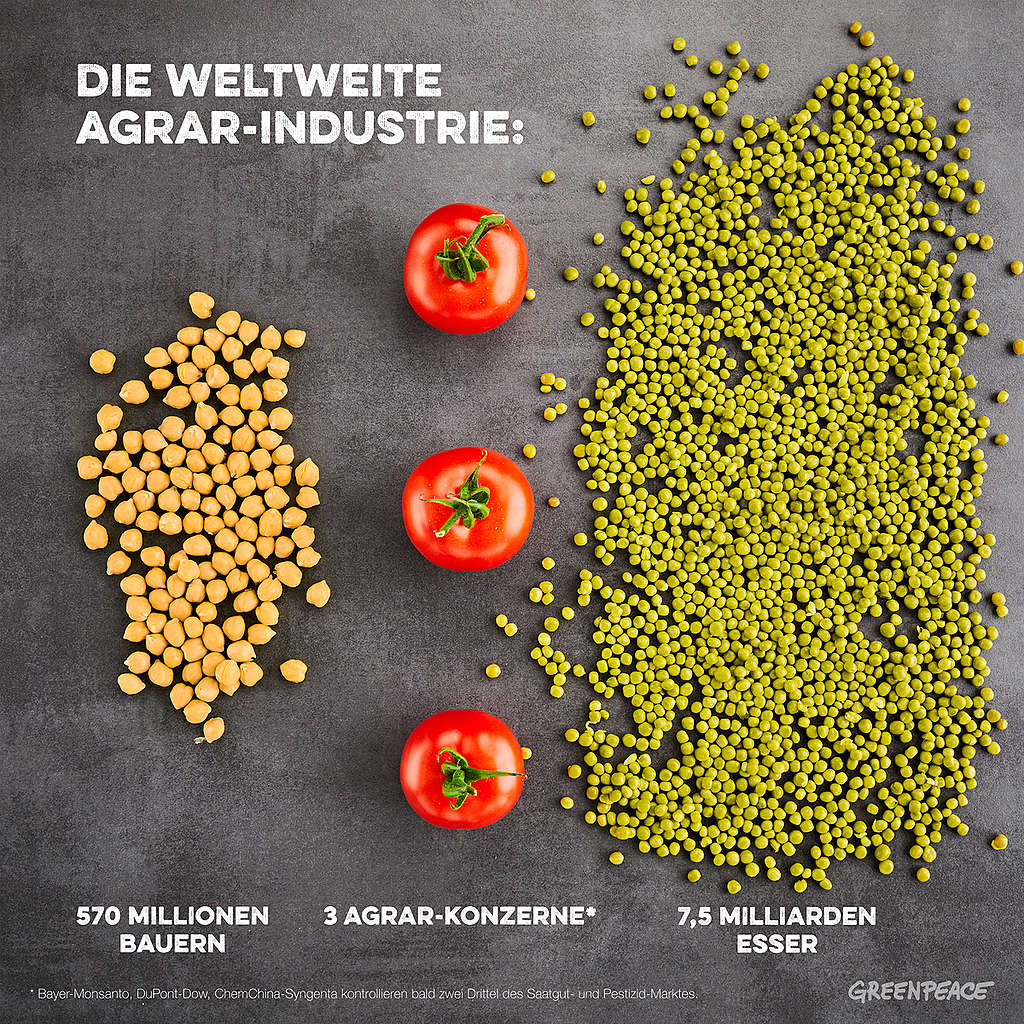

Since the scientists of Monsanto began breeding and producing seeds professionally, creating hybrids and genetically modified seeds in specialized laboratories, seed production has become a huge global business. It aims to encourage farmers all over the world to apply the same industrial model of agriculture.

However, this industrial mode of production puts small-scale farmers in great danger, as they lose control over their own land, soil, and seeds, and ultimately over their food.

Instead of using their own seeds that have been carefully selected over the years, farmers are pushed to use industrial seeds, that are expensive and often not adapted to the specifics of the region.

Luckily, there’s resistance against Monsanto among some farmers who are committed to reviving their traditional practices of seed saving, storing, and selection. They are determined to organize themselves to spread information on how seed laws give agribusinesses control over farmers’ lives and ultimately over all of our lives, by determining what to plant and what to eat.

Implications of Monsanto’s reign on South Africa’s agricultural future and its smallholder farmers

This is how Monsanto and Bayer gain control of the agricultural industry through seed.

1. Reduction in competition in the seed and agrochemical markets

The South African market for maize, soybean, cotton, and other commodity crops is already controlled by an oligopoly.

Monsanto’s already significant market power, particularly in genetic traits and herbicides was worsened by the merger with Bayer who offered its complementary product offerings and access to additional capital to capture new markets on the rest of the continent.

Given this dominance by one entity in South Africa’s seed market, it diminishes the choice available to maize, soy, and cotton farmers.

2. Decreased innovation

The world needs innovations that serve to bring about socially just and climate-resilient societies. The kind of thinking necessary for this does not tend to happen in in-house ‘captive’ research and development models which are principally for profit.

This kind of innovation tends to happen through collaborative relationships based on a genuine exchange of knowledge.

In the agricultural sphere, these kinds of relationships would include participatory research with agendas set by farmers who provide input not only into the challenges that research and development needs to meet but also into how such research is conducted.

In this sense the consolidation of the industry into three major global players further entrenches the enclosure of knowledge generated in research and development processes, using intellectual-property regimes, among other tools.

3. Further entrenchment of intellectual property rights regimes

Patents and other forms of intellectual property rights effectively allow corporations like Monsanto to play a gatekeeper role in the agriculture sector.

Companies with a dominant market share not only make it more difficult for smaller companies to enter the market, but also shape the market and its future pathways in ways that preclude opportunities for a more agroecological model of farming to emerge, one that is built on social justice and equity.

4. Increase in prices of agricultural inputs

Consolidation resulting in a lack of competition is linked to price increases for agricultural inputs.

Biotech seeds cost about twice as much as conventional seeds and these costs keep rising. Yet, there is no visible corresponding benefit in terms of higher yields or greater returns to farmers.

This is of particular concern in South Africa where most maize is genetically modified and while it might generate higher yields, it is at a greater cost – both environmentally by reducing biodiversity and the accompanying inputs polluting groundwater – and economically by placing farmers on a technological treadmill that requires them to buy seed anew each year.

Any significant increase in input costs, particularly seed, has a dramatic effect on the ability of African small-scale farmers (more predominantly in South Africa) to use commercial seeds to remain financially viable.

5. Corporate controlled seeds

Monsanto patents their herbicide-resistant GMO seeds and hence restrict their reuse. Farmers are not allowed to reuse Monsanto’s seeds and must buy the seeds soon after harvest to replant. This is just a small taste of Monsanto’s and Bayer’s seed empire.

This monopoly is achieved by buying up small seed sellers and patenting those seeds So that those seeds couldn’t be traded or planted without legal reparcations.

6. The deadly debt cycle

Once farmers start using GMO seeds and these herbicides they can’t stop or find it difficult to switch to organic varieties.

In India, for example, Monsanto’s bt cotton GMO seed is king. 90-95% comes from it. Upon its commercialization in 2002 the seed promised a decrease in pesticide use while still maintaining pest control and higher yields. However, its use has led to an increase in pesticide use because pests like bollworms grew resistant to them. Yields have also declined as the acreage of this type of cotton has increased.

These GMO seeds also increase in price constantly due to this predatory seed empire that has been created. The cost of labor and these pesticides is a burden to the farmers causing farmers to turn in little or no profits in their craft.

Monsanto’s isn’t the only way,

The current industrial food system based on monocultures, widespread use of agrochemicals, commercial/patented seeds, and genetically modified seeds is a major contributor to the disappearance of 75% of plant genetic diversity in the last century. You can learn how to save seed here.

Monsanto has positioned itself at the very summit of the global seed industry through a combination of acquisitions/mergers, intellectual property rights, and aggressive lobbying, both directly and through proxy organizations and individuals.

Monsanto undoubtedly dominates the global GM seed market. It holds a similarly imposing position in the global market for agrochemicals, mainly through its non-selective herbicide brand, Roundup.

Monsanto’s assent in the South African commercial seed market has been equally meteoric.

Monsanto is unlikely to give up on these markets, as it affords them an ideal testing

ground for their efforts to penetrate much larger markets throughout Africa, where hundreds of millions of potential customers are to be found.

Let us not leave the control of our food supply in the hands of global biotechnology companies.