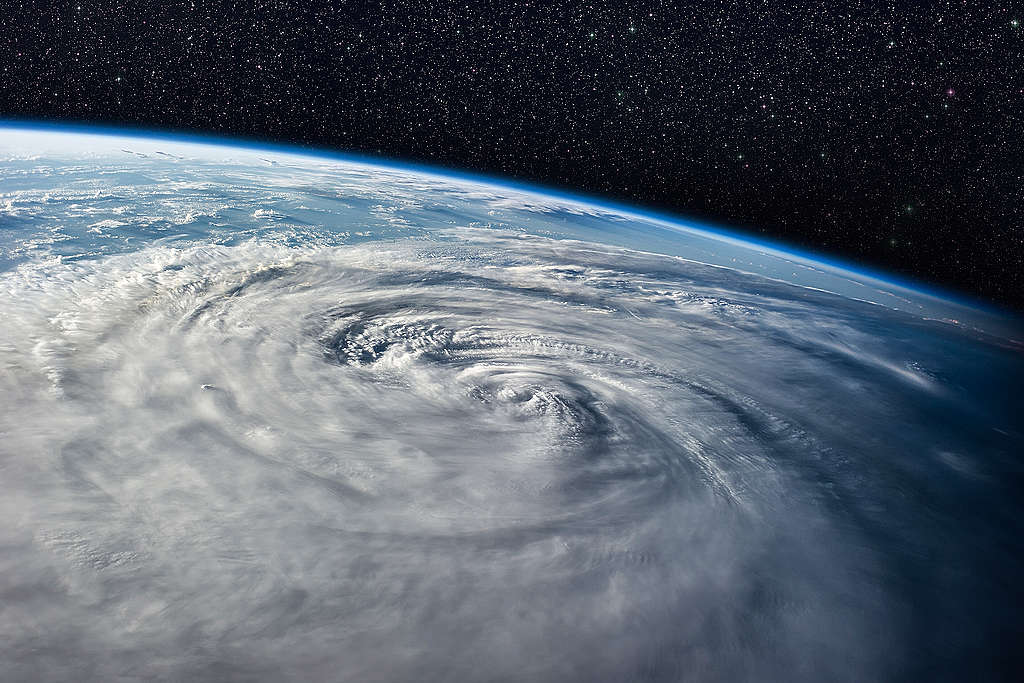

Typhoons are no joke. They can be immensely destructive and even life-threatening with barrelling winds screaming at speeds in excess of 250 km/h (equivalent to the average pace of a bullet train), extreme rainfall that can trigger deadly landslides and mudslides and storm surges capable of engulfing entire coastal communities.

While typhoons, or as they are more generally called, tropical cyclones, are natural weather events, and people have been preparing and protecting themselves for centuries against their worst effects, climate change is altering how typhoons are being formed and changing how they impact us.

And not in a good way.

The last report from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) looked at tropical cyclones region by region. For East Asia they said:

“The rate of intensification and number of strong tropical cyclones have increased, and tropical cyclone tracks likely migrated poleward.”

In this article, we sift the latest science to unpack exactly what that means, why it’s happening, and what we should do about it.

There are three key takeaways from the IPCC statement above. Let’s take each one in turn.

The IPCC says: “Rate of intensification has increased”

What this means:

While there is no firm evidence that the average annual number of tropical cyclones forming in the Western Pacific (that’s the part of the ocean around East Asia and Southeast Asia) has significantly changed, typhoons on average are getting stronger. This study published in 2016 found that typhoons hitting East Asia and Southeast Asia had intensified 12 to 15% since the late 1970s.

The IPCC says: “Number of strong tropical cyclones has increased”

What this means:

That same study also found that the number of category 4 and category 5 tropical cyclones (these are storms with sustained wind speeds greater than 209 km/h and 252 km/h, respectively) at least doubled since the late 1970s. Since the number of typhoons has not significantly changed, the proportion of severe typhoons and super typhoons in the East and Southeast Asian region has also doubled.

In East Asia alone, severe typhoons and super typhoons have nearly quadrupled from less than one per year to more than four per year since the late 1970s. As a proportion of the total number of typhoons, they have jumped to 60% from around 20%. That means more than half of all typhoons have a good chance of belonging to the most destructive categories.

If you want to know more about super typhoons and the worst ones to strike East Asia in recent history, click here.

The IPCC says: “Tropical cyclone tracks likely migrated poleward”

What this means:

Typhoons are changing where they start and then, where they go.

Typhoon genesis — or where they first form — is shifting northwards (or polewards). And once they are formed they are tracking more often in a northwesterly direction. This has three main outcomes — (1) typhoons reach their peak intensity at higher latitudes; (2) they are more likely to be at a higher intensity when they hit land; and, (3) they are hitting China mainland, Korea, and Japan more frequently and Hong Kong and Taiwan less frequently. This study, which documents this migration, also warns that climate change may exacerbate these changes in the years to come.

Why is this happening?

Climate science is complicated but there is good consensus that these changes are at least partly due to how climate change is warming the oceans. In this study, mentioned above, they tracked sea surface temperatures and found that they had risen a lot in the waters around East and Southeast Asia between 1977 and 2013. However, in the middle of the Pacific, the jump was much smaller. Typhoons in East and Southeast Asia have become measurably more powerful, while those in the open ocean have changed little.

For the most simplest explanation, we can think of warmer waters as having more energy, so when a typhoon forms over an expanse of warm ocean, they get that extra boost from that extra energy.

Why does this matter?

The more intense a typhoon is, the more damage potentially it can do when it makes landfall — ripping out trees, destroying buildings, flooding cities, and burying villages under mudslides causing untold losses.

Tropical cyclones have inflicted great devastation in both economic terms and human lives. Between 1970 and 2019 in Asia, almost 1 million lives were lost and $2 trillion were reported in economic damages from natural disasters. Almost half of these disasters were floods and more than a third were caused by storms.

What can we do?

Coming up at the end of this month and running through to 12 November, the next big world summit on climate change — this one called COP26 — will be held in Glasgow in Scotland. The IPCC’s recent 6th Assessment Report confirmed that the 1.5C warming limit is still within reach, from a physical perspective, but only with cuts that bring carbon emissions to Net Zero and beyond.

This is it.

This is the key moment when global leaders — who all know what climate change is, who all know what climate change is doing to our planet, and who all know what we can do about it — have the chance to act like real global leaders. They must agree to cut fossil fuels and those cuts have to be huge and they have to be fast. We must halve global emissions by 2030 to avoid the worst effects of the climate crisis.

We need them to ensure their words count, that their promises count. They need to have strong, concrete, feasible and tangible roadmaps to making those cuts and making those cuts starting now.

This is the last decade we have to stop a full-blown and runaway climate crisis; that’s why the world will be watching what goes on at COP26. But it’s not only about averting a global crisis, world leaders also have a unique opportunity at this summit to create a stronger and fairer global economy by focusing on building wealth with green industries and helping poorer nations meet their carbon neutrality goals.

If the world continues to fail to act big, the cost of saving ourselves in the future will be exponentially higher until we will reach a point when it will no longer be possible.

Final words

While we’ve quoted dry scientific papers and data in this blog, none of what is happening to our weather is just academic. It is happening now.

For example, while this blog was being written, Typhoon Kompasu was tearing through Hong Kong. The signal 8 superstorms (out of a scale up to 10) shut down the city closed schools, financial markets, and halted flights. Earlier it had led to the deaths of at least nine people from flooding and landslides in the Philippines. The impacts of the climate crisis are already here.

Act now and demand your government to lead by example and show ambitious emissions-cutting plans and real solutions to halve global emissions by 2030.