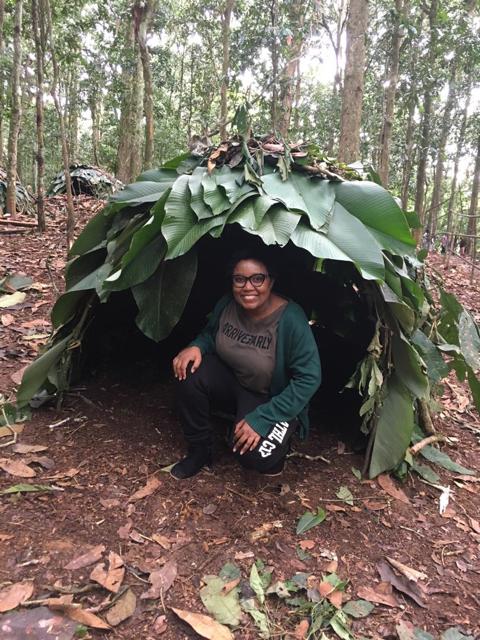

When I think of the forest, I remember playing in it. We would build huts of sticks and moss, and vehicles from bamboo trees. Getting lost in the forest was a real adventure. We used to turn the forest into a navigation game. We could get a sense of orientation without a compass or a GPS.

My family lived in a forest area in the central region of Cameroon. I have known the forest ever since I was a child. My birthday is on the 21st of March – the international day of forests – so I feel uniquely connected to forests.

I would go with my brothers, sisters and our friends into the nearby forest to collect seasonal fruits off the trees (bush mango, oranges, lemons). We would collect traditional medicinal herbs and scrape the tree barks with our grandma to treat our stomachaches, especially after eating too much of those fruits.

Playing and jumping in the bushes, looking for food and building materials, these were some of our favorite moments as children in Cameroon. The forest served me with free therapy sessions. When I was sad or needed to reflect, I used to go and rest under a tree. Alone, I could enjoy the shadow created by the branches. Listening to the squirrels’ feet clambering in the trees or the birds singing, chirping, croaking and shrilling, it was a peaceful treatment for my mind.

Life seemed so simple then. We had a place where we found ourselves connected. The air was pure and fresh and we did not know many of the diseases we do now. The tranquil environment in the forest was reflected in the unity of our communities. There were hardly any conflicts over land and when they occured they were solved peacefully around a fresh cup of palm wine.

But now I’ve witnessed the consequences of forest destruction for industrial agricultural plantations growing crops, rubber or palm oil or monoculture tree plantations. Seasons rapidly began changing from cold to very hot. Children were killed by speeding trucks carrying timber. Natural treasures were being plundered as resources for the selfish interests of a small group of people.

The humid rainforest has gone dry in many areas after intense logging, and the rich life that had been there has now turned into a story of displaced communities and fleeing wildlife.

When I walked in the forest today, as I try to do on every one of my birthdays, I recalled how it was during my childhood. I thought, why are they cutting down so much of the forest and what is the benefit of it for the people living here?

This is not unique to my country. Everywhere around the world the promise of “development” through logging has never served the people who live there. Only a handful of foreign companies and well-connected insiders are getting wealthier. Are they aware of the climate crisis? Did the loggers ever go through experiences in the forest that were similar to mine? What can we learn from Indigenous and local communities, who have been the natural guardians of the forest for so many years? What richness of knowledge is at risk of being lost, as I’ve seen them cast out of their homes? And what role do they ever get in the debate around the climate and biodiversity crises?

Joining the fight through the forest campaign of Greenpeace Africa six years ago gave me an opportunity to defend my forest and stand for the rights of the people living here. Working with communities and learning to see the forest through their eyes, hearing their cry the forest is destroyed in the name of “development”, makes me more eager to continue to stand with them and for their rights.

Here in Cameroon, many of the plantations that have replaced our natural forests are in fact tree monocultures. But not everyone understands the difference between a tree monoculture plantation and a natural forest. Even some governments. By replacing natural forests with monoculture tree plantations, not only are human communities and endangered species put at risk, but enormous stocks of carbon are released into the air.

Carbon is mostly stored in the thick stems and deep roots of trees that are hundreds of years old. Planting new trees to replace ancient forests is not a solution. It just serves to greenwash the conscience of executives in oil and gas companies, declaring one trillion trees will be planted and “offsetting” CO2 emissions from extractive industries with artificial forests is part of the problem. Planting trees with one hand, while the other one is pumping oil out of the ground is like putting a band-aid on an arm that has been dismembered.

Only a natural forest can be home to rich biodiversity, including rapidly disappearing medicinal plants. Only a natural forest can be a home to Indigenous and local forest communities. The solution requires acknowledging their unique role in good management of forests and recognizing their rights over their land. Give them back the forest. Ensure their participation and inclusion in all policies.

Seeing the scale of forest destruction in my land and understanding the risks for the entire planet, celebrating my birthday has become more difficult in recent years. I hope that this time around, my cry as someone who always loves to visit the forest – along with the cries of Indigenous and local communities who must live in the forest – will be heard by many more of you. That would be the perfect gift for my birthday. It would help bring a smile to my face and to so many more.

Go here to read more from Greenpeace about why plantations are not forests.

Sylvie Djacbou Deugoue is a forest campaigner for Greenpeace Africa, based in Yaounde, Cameroon.

Discussion

My Pm.Abiy Ahmed already Started green legacy !!!

Thank you for sharing with us.

Plastic is one the worst things in this world

Thank you for your comment. Indeed 😔, we need to stop it from worsening, kindly take action here>>>> https://act.gp/3wmbamE

I love all beautiful i seen and fantastic and clean fields

Thank you for your comment.