PRESS RELEASE

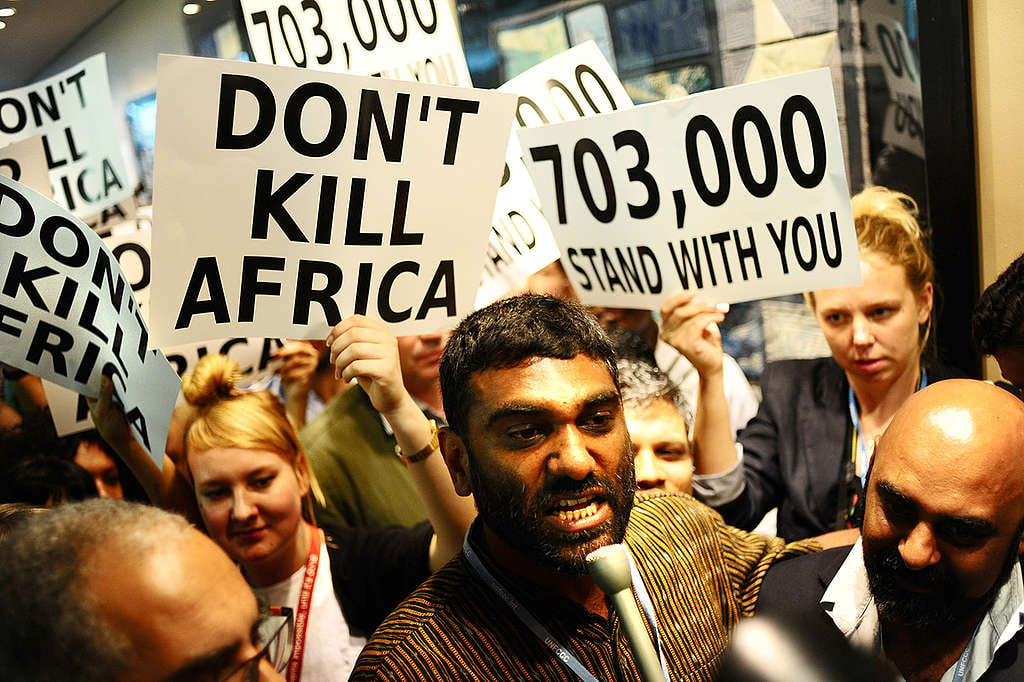

Johannesburg, 23 November 2020 — South Africa saw a sharp decrease in Sulfur Dioxide (SO2) emissions in 2019, bringing the country’s emissions to their lowest level on record, according to new research by Greenpeace India and the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA). [1]

A significant drop in emissions would increase the quality of life for thousands of South Africans who suffer from respiratory and other illnesses as a result of air pollution, and would save South Africa billions of rands in medical costs and work days lost.

The fall likely resulted from temporary reduction in coal-fired power generation, which led to load shedding. While encouraging at first glance, South Africa’s emissions are still well above what is recommended by the World Health Organisation[2]. The Kriel area in Mpumalanga was identified by Greenpeace research in 2019 as a global hotspot for SO2 emissions, and is still a global hotspot by annual emission amount. It is also the largest hotspot in Africa and the largest hotspot driven by coal combustion worldwide[3].

“It is so unfortunate that we cannot celebrate this reduction in emissions as an indication that the South African government is trying to protect the people of South Africa. Instead, it is an indication of their ineptitude at dealing with corruption at Eskom. It is years of mismanagement that cause our air pollution levels to drop – not because there were deliberate measures taken to drop them, but because the power tripped,” said Nhlanhla Sibisi, Climate and Energy Campaigner for Greenpeace Africa.

Further research is needed to better understand the drop in emissions. Data suggest that load shedding may account for the reduction in emissions from 2018 to 2019 (2019 was one of the worst years of load shedding for South Africa, exceeded in severity only by 2020); the national lockdown implemented as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic may account for the decrease in emissions in 2020[4]. In either case, the decrease is categorically not due to any proactive action by government to curb South Africa’s air pollution crisis – on the contrary, the National Air Quality Officer has yet to announce her decision on whether to grant Eskom further postponements from compliance with MES, and the DEFF gazetted the weakening of South Africa’s SO2 emissions limits in March 2020 ( with the new limits effective from 1 April 2020).

Exposure to SO2 pollution at the scale at which it is present in South Africa can lead to severe health problems, including dementia, fertility problems, reduced cognitive ability, heart and lung disease, and premature death[4]. In addition, combustion processes which release SO2 into the air – such as burning fossil fuels such as coal – also release other pollutants, including fine particulate matter and greenhouse gases which contribute to global heating and, inevitably, drive the growing climate crisis [6].

“The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated action around the world aimed at driving Just Transitions away from fossil fuels; yet the South African government continues to drag their feet. There is no more time to waste. Investors are pulling out of coal projects locally because they recognise the dangers posed by burning fossil fuels. South Africa could lead the world on this journey, if our politicians would only wake up,” ended Sibisi.

Greenpeace urges

- President Cyril Ramaphosa to halt all investment in fossil fuels and shift to safer, more sustainable energy sources, such as wind and solar,

- Minister of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries, Barbara Creecy to strengthen SO2 emissions standards by reinstating South Africa’s 500 mg/Nm3 minimum emission standard and applying flue gas pollution control technology at power plants, smelters, and other industrial SO2 emitters,

- South Africa’s National Air Quality Officer, Dr Thuli Khumalo, to enforce existing minimum emission standards,

- Minister Creecy to hold carbon majors accountable for their emissions resulting from the use of fossil fuels by implementing and enforcing national environmental legislation,

- Minister for Mineral Resources and Energy Gwede Mantashe to revise the commitments made in the Integrated Energy Plan and,

- abandon plans for installing new coal-fired power stations of 1500 MW capacity scheduled for 2023 and 2027, and

- increase uptake and implementation of renewable energy generation capacity through radical and deliberate policies and programmes, and

- Minister Jackson Mthembu to ensure the development of a comprehensive and inclusive Just Transition programme that moves the country away from the use of fossil fuels to renewable energy.

ENDS

Notes

The global ranking of SO2 hotspots can be found here.

[1] Researchers used NASA satellite data and a global catalogue of SO2 emission sources to detect emission hotspots. NASA’s satellite technology provides near worldwide estimates of SO2 emissions. Researchers analysed the data to identify source industries and emission trends. NASA estimates that the MEaSUREs catalogue, which is the main source for this report, accounts for about half of all known anthropogenic SO2 emissions worldwide.

[2] More information on the WHO’s air quality guidelines can be found here.

[3] See page 17 of the report. Mpumalanga was also identified as a global Nitrogen

[4] This conclusion is based on measurements by NASA’s Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI). See pages 18-19 of the report for more detail.

[5] A more detailed analysis of the health impacts that result from noncompliance with minimum emission standards can be found here.

[6] In 2020, Greenpeace Africa released new research that examines the relationship between the climate crisis and extreme weather events in Africa. The report, Weathering The Storm, can be accessed here.

Contact details

Chris Vlavianos, Greenpeace Africa Communications Officer, +2779 883 7036, [email protected]

Join the international movement of people calling for clean air. Sign the petition here.

Discussion

Yes I need it

Thank you for your support.