All articles

-

There is nothing wrong with Eskom … Not!

Yes, you read this right 😉. Their power stations aren't ancient. Kusile didn't cost millions and is not a disaster waiting to happen. I hope you understand that I'm being super sarcastic here. However, there is a different angle I would like to add to this piping-hot topic.

-

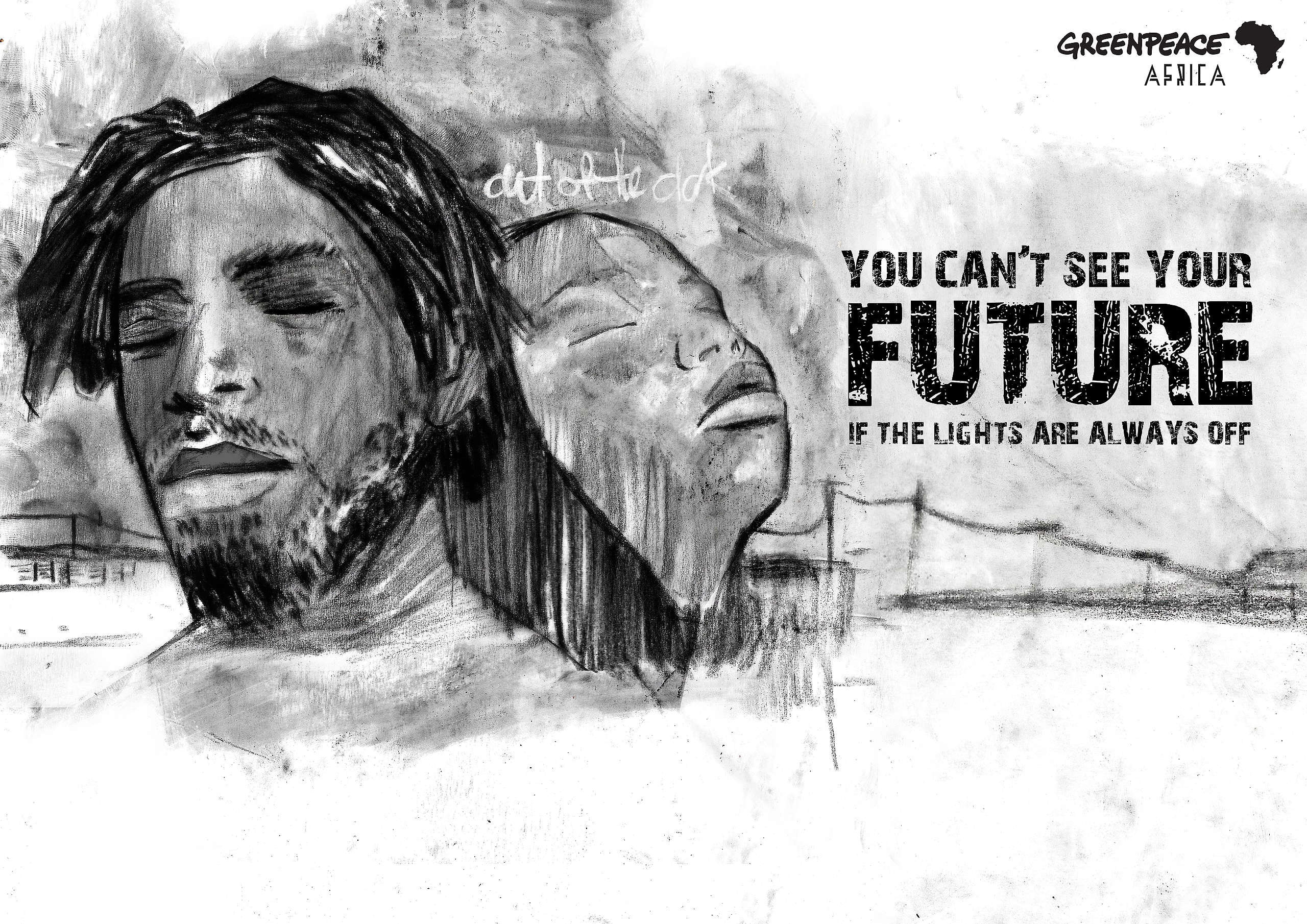

An inevitable end of an era?

Will this be the year the South African government prioritises clean, renewable energy over dirty coal to keep the country running?

-

COP15 recognises Indigenous Peoples’ work, but won’t disarm the threat of mass extinction

Montreal, Canada, 19 December 2022 – At the final adoption of an agreement at COP15, Greenpeace welcomes the explicit recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ rights, roles, territories, and knowledge as the…

-

Just transition: Air pollution by oil giants is trapping impoverished communities into generations of injustice

The “just-transition” cannot only focus on how the new green world caters for those affected by the energy transition, it must also see to those that have to live with the legacy of the old polluted world. Communities such as those in South Africa’s South Durban Basin are trapped in a cycle of poverty and illness…

-

Civil society and community organisations to challenge Sasol over insufficient decarbonisation plans and ongoing pollution

On Friday 2 December, Sasol Limited will be hosting its 43rd Annual General Meeting of shareholders (AGM). The hybrid meeting will be attended both virtually and in person by shareholders.…

-

Greenpeace Africa applauds Treasury for upholding Carbon Tax

"Greenpeace Africa commends the National Treasury for upholding the carbon tax and not giving into the pressure from polluting businesses."

-

Greenpeace Africa responds to Just Energy Transition Investment Plan

04 November, Johannesburg – Tonight, on the eve of the commencement of the twenty-seventh United Nations Climate Change Conference, President Ramaphosa released the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) Investment Plan…

-

A safe and fair future for all can be delivered at COP27

The burning question at the upcoming 27th UN Climate Conference (COP27) is whether richer, historically more polluting governments are going to pay up for the loss and damage caused by climate change.

-

Top polluters’ party spoiled by projection on nearby stadium: “Fossil fuels kill”

Tonight’s gala dinner for fossil fuel industry chiefs and petroleum ministers participating in the Africa Energy Week in Cape Town was interrupted by bright projections on the overlooking Cape Town Stadium: “Fossil fuels kill” and “The future is renewable."

-

With new coal uninsurable, insurers start to move on oil and gas

Insurance company restrictions on oil and gas are finally starting to catch up with those on coal, according to new data from the Insure Our Future campaign, co-published with Greenpeace.