How a few pioneers went to one of the most remote regions on Earth just to get a seat at the bargaining table of Antarctic Treaty Nations, then proceeded to convince global leaders to believe in the dream of having Antarctica protected as a world park.

Antarctica: The Final Frontier

Antarctica is the only continent that remains relatively untouched by human interference; it’s arguably the only pristine wilderness left on Earth. Scientists can use this unique environment to gain insight into pollution and climate change in a way that cannot be achieved elsewhere.

Yet in the early 1980s, commercial exploitation threatened this delicate ecosystem. There is strong evidence for the existence of oil and mineral deposits under the ice, meaning governments and companies were lining up to start prospecting. This is frightening because the arctic is particularly susceptible to oil spills and other types of pollution. A single spill could devastate the area.

Greenpeace World Park Base

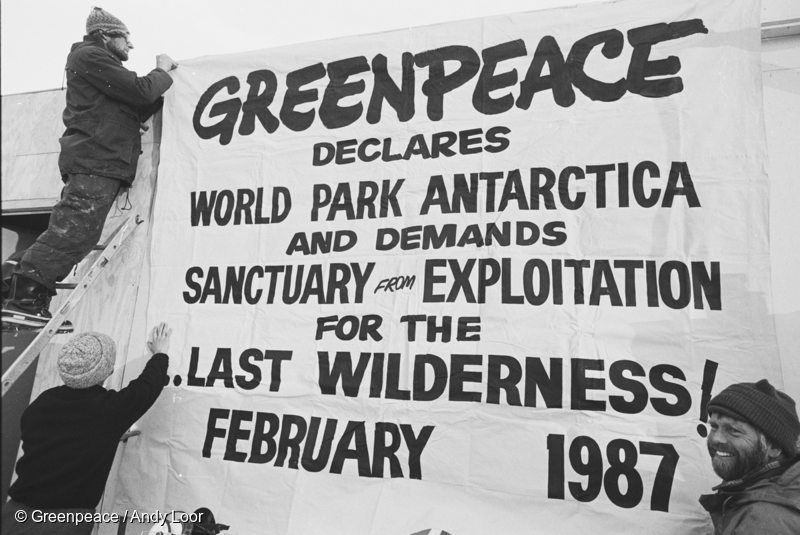

The idea for a campaign to make Antarctica a ‘World Park’ was first suggested by Greenpeace in 1979. However, rules dictated that we would have to set up a permanent base on the ice if we were to have a voice at the Antarctic Treaty table. Only a base would allow us to challenge national territorial claims with an argument that Antarctica should be preserved as a global commons—belonging to no one.

No non-governmental organization had ever set up a base in Antarctica; there were many obstacles, both political and practical. In 1987 the MV Greenpeace moored in the Antarctic (after weather had halted their first attempt) and a few weeks later the World Park Base was operational. The intrepid Greenpeace pioneers stayed from 1987 to 1991.

The Antarctic Treaty Nations and One NGO

The team monitored pollution from neighboring bases and held other nations accountable for their actions. Greenpeace made headlines when 15 protesters blocked the French from building an airstrip at Dumont D’Urville. The construction work was controversial because it involved dynamiting habitats of nesting penguins. French scientists even admitted an airstrip violated terms of the Antarctic Treaty.

During the protest French construction workers reacted angrily to a Greenpeace demonstration; workers forcibly evicted the protesters and smashed up a hut we had erected. Despite continuing threats of violence, the protesters returned to occupy the landing strip for a second day. The French later abandoned plans to build the airstrip.

The professionalism of our operation gradually earned respect from other Antarctic Treaty Nations. After seven years of campaigning, Greenpeace went from being perceived as an almost despised outsider in Antarctic Treaty affairs to being a respected player in negotiations for the future of the continent.

Antarctic Treaty Nations Adopt an Environmental Protocol

In 1989, the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska undermined any oil company’s argument that drilling in ecologically sensitive areas could be conducted in a safe, environmentally friendly manner. Greenpeace offices worldwide lobbied their governments to take a responsible position protecting the Antarctic, joining forces with other non-governmental organisations and eliciting support from personalities including Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, Jacques Cousteau, and Ted Turner.

Gradually more and more Treaty signatories were persuaded of the merits of making Antarctica a World Park. In 1991, the members of the Antarctic Treaty agreed to adopt a new Environmental Protocol, including a 50-year minimum prohibition on all mineral exploitation.

This meant ensuring that knowledge to be gained from Antarctica’s unique environment could be maintained for years to come, a victory for people, penguins, and the environment. It showed that people power was able to overcome commercial interests, sending a message that Antarctica could not be mined for profit with a socially conscious public around to fight back.