A home lost, and the fierce will to rebuild

Patrick Michell and Tina Grenier want a house that can withstand flames.

After losing their home and hometown in the devastating Lytton fire of June 30, 2021, the husband and wife are doing everything in their power to make sure they never have to live through that again.

“I’m sixty years of age. I’ve lived in this very town all my life. Everywhere I go, the environment is changing,” warns Patrick. “The very conditions that granted our ancestors life are changing dramatically, and it’s not for the better.”

Knowing that wildfires will only become more frequent and more intense due to climate change, he and Tina submitted a proposal to rebuild their home using fire-resistant and climate-resilient materials. Residential rebuilds in Tina’s home community of Tl’kemtsin (Lytton First Nation, or LFN) received federal funding from the Indigenous Services Canada Emergency Management Assistance Program, but last month, a curveball was thrown their way again when the LFN council did not approve their proposal.

It’s difficult to do something new or different—and that’s fully understandable, Patrick tells me over Zoom, a couple of weeks after the decision and a few months after I visited him on Nlaka’pamux land this past August. Their replacement home would have been the first house in the region using uncommon (but tested) materials that can withstand external temperature and flames for longer than conventional materials.

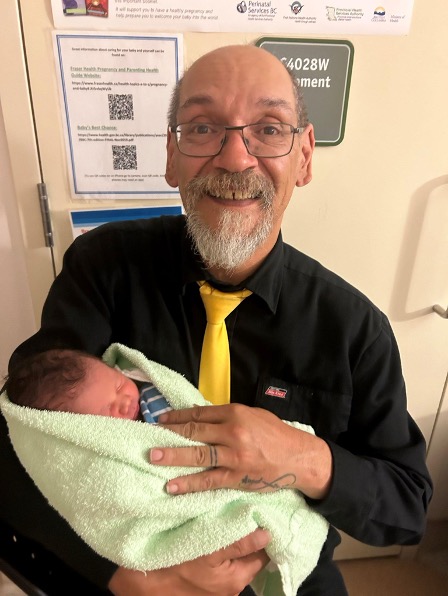

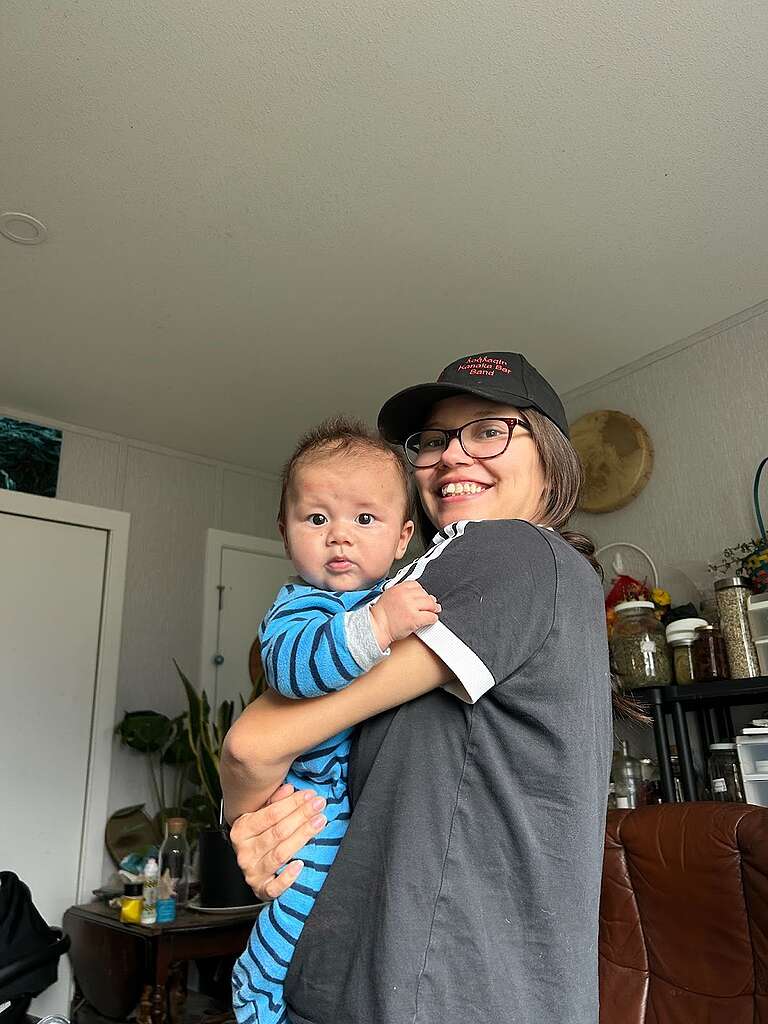

LFN did approve a 2,400-square-foot rebuild footprint, which is much smaller than the family’s original six-bedroom home, which housed four generations under one roof. This means, heartwrenchingly, there is no room for the couple’s daughter, Serena, her husband, and their two young boys.

So, Patrick and Tina are now advancing the smaller design with the best-known options in a world of imperfect choices. Their old home was fully paid off but uninsured, so rebuilding on their own would be incredibly expensive. The couple is very grateful for the support they are getting from Canada and LFN, and they hope to move out of their temporary house and into the new home next year. Serena’s family will continue to rent an apartment at T’eqt”aqtn’mux (Kanaka Bar Indian Band), about 20 kilometres south.

The news has been difficult to process.

“Climate change and its impacts are mental, emotional, physical, spiritual, and please don’t forget financial,” Patrick warns. “The longer you’re displaced, the worse it gets.”

Carrying the weight of too many disasters

Regions like B.C’s Fraser Canyon have been through the ringer. Just coming out of Covid-19 in 2020, disasters cascaded in rapid succession in 2021: the Lytton fire in June; the atmospheric river and floods in the fall; and the plunging temperatures of December’s winter freeze-up. Since then, it’s been four consecutive years of wildfires, evacuation alerts, and evacuation orders. Meanwhile, community members continue to recover and heal from the traumatic wounds of residential schools, which echo across generations.

This compounding and consecutive trauma makes it difficult to get out of despair and fight or flight mode, says Patrick. So, in 2022, he retired as Chief of the T’eqt”aqtn’mux to help his family recover. Once they were stabilized, he spent time working with LFN as their Rebuild Director.

A husband, a father, a leader holding many worlds together

Patrick juggled these hats with intention and perspective. As a husband, Patrick is happy that he and Tina will soon have a home again. The uncertainty (and exhaustion) of this part of their journey is over. And while they’re disappointed in the decision about their house, they’re moving forward. As a father and grandfather, Patrick is turning his attention to finding a nearby forever home for Serena and her family. And in his former role as LFN Rebuild Director, he had his eyes on bringing more climate resilience and self-sufficiency to the region.

I have to believe. If I don’t keep the faith, if I don’t stand up today, who’s going to look after my children and grandchildren tomorrow?

Patrick Michell

“Hope flows from action”: A mantra for the Anthropocene

Patrick is a force of nature behind many climate resilience stories. While Chief of the Kanaka Bar Indian Band, he oversaw teams to implement projects that strengthened community self-determination, such as gravity-fed water storage systems, small-scale solar, controlled environment agriculture, and much more.

He tries to be an “eternal flame of optimism”, and you’d be hard-pressed to find a more determined person. He presents when asked to do so—wherever he’s asked to do so— and pictures of his children and grandchildren are peppered across his many public talks.

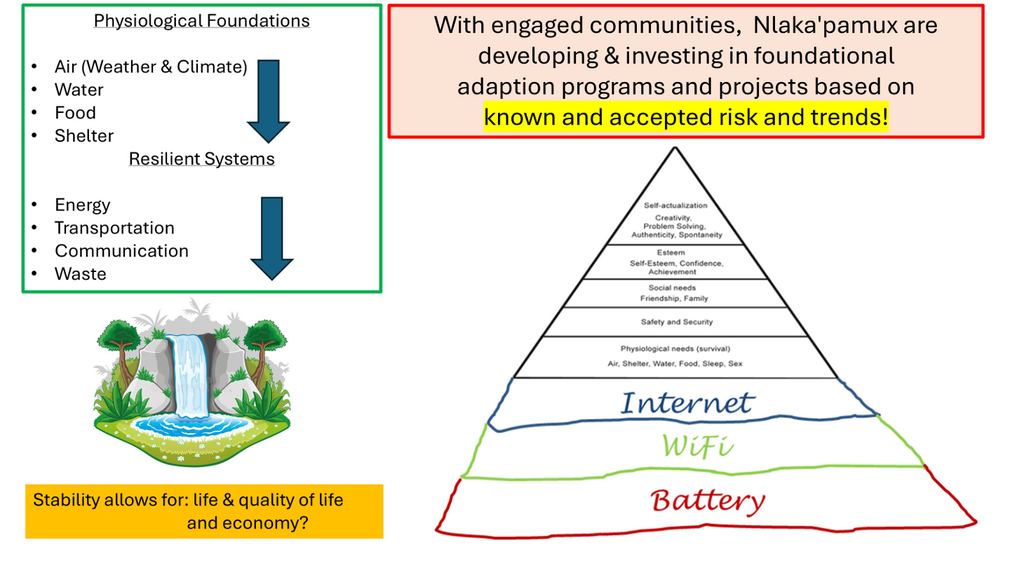

Ever-cheeky, he uses the slide below to introduce attendees to what he calls “a logic flow and waterfall of strategic investments.” In other words, fund the physiological foundations of life first, and then attend to other needs and systems. (And according to Patrick’s grandkids, wifi is fundamental).

There’s a larger-than-life quality to Patrick’s resolve. It’s contagious—something he’s been told again and again. And while he’s modest about it, I’ve learned how much intention he brings to his conversations, how aware he is of the apathy that set in because of past trauma, climate grief, compounding catastrophes, and a rigged economic system.

For Patrick, the only cure is action, as he wrote in a piece for the Canadian Climate Institute.

“Hope flows from action. Quit your yakkin’ and start doing!” he says, half-jokingly.

For that, you’ll need to connect to the reason you wake up and get out of bed each day. Patrick’s reason is obvious. His love for his family is at the root of everything we talked about back in August, when he took me, my partner, Charlie, and our toddler, Meroë, out on the land onto Nlaka’pamux territory.

“When we have a ‘why’, we get up and do,” he explains. “The success that I’ve had is because I’ve had teams around me that believe in the same ‘why’.”

A community rising, one home and one breath at a time

Since 2021, LFN has successfully moved 42 displaced families from hotels into temporary modular homes. Last year, it began constructing 80 new homes, slated for completion by the end of 2026. And in the next ten years, LFN hopes to build 175 more new homes.

When we spoke to him first (during his time as Rebuild Director) Patrick said that the Nation is also taking steps to reduce the risks to current houses from flames, embers, and radiant heat, through measures like new metal roofing, installing proper soffits and fascia board, repairs to venting, replacing siding with non-flammable materials, and (most importantly) removing the fuel that feeds the flames. This means clearing brush, grass, and scrub from around dwellings and critical infrastructure

LFN also built a temporary café, general store, large gathering space, and a hardware store to serve the wider area of Lytton. A new food processing centre, the Y’Kem Food Hub, is currently under construction. This will be a place where people can bring their meats, fruits, and vegetables for processing and storing through freezing, canning, drying, salting, smoking, jamming, and juicing. Surplus food not needed by the family can be sold to generate income.

As we gather, our elders share stories of the past, of the vibrant life that once thrived here, of our traditions and of our deep connection to the land … They remind us that fire, though destructive, can also clear the way for new growth.

– Rainbow Djo, LFN Communications Manager (see video below)

The Lytton First Nation shares its community-led rebuild and recovery experience, showcasing voices from across generations in this short video.

When support falls short and communities are left exposed

Rural Indigenous communities like Tina and Patrick’s have been at the forefront of climate disasters and recovery for years. Their innovations are leading the way. Yet, despite having identified clear infrastructure needs to mitigate the impact of these disasters, many remain underfunded by federal partnership mechanisms.

In 2022, a report by the Auditor General found that the federal government spends 3.5 times more money responding to and recovering from emergencies than on supporting communities to prevent or prepare for them. These kinds of unmet structural mitigation needs are highest in British Columbia and Alberta.

Every dollar spent on adaptation yields up to $15 in future economic benefits. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, Patrick reminds me. He hopes that when Lytton’s rebuild is complete, the cost of rebuilding serves as a wake-up call for decision-makers to break the cycle of addiction to rapid response.

“If the federal government had just provided resources like money before the fire to do renovations, retrofits, and remove the fuel, we might have lost two or three homes,” he reasons. “Instead, we lost 42 homes in 2021 and seven more in 2022.”

“We need to prepare for more events like this,” agrees LFN Councillor Amanda Adams, addressing Tl’kemtsin members in a recent video recapping a gathering to kick off the LFN’s community resilience plan.

“The plan will be for LFN, by LFN—meaning that the voices of our members, youth, and Elders will be central,” she says. Through surveys, events, and door-to-door outreach, the LFN will get input from the community and complete the plan in 2026. “Our people already hold deep knowledge of how to care for and survive on our changing lands.”

Returning to teachings that have always kept people safe

Renewing traditional practices, like cultural burns, she adds, starts with teaching them to youth. As adults, they will then have the confidence to put these teachings into practice and, in turn, pass them on to their families.

Stop the fossil fuel insanity

Facing the truth: the harm done, and who must answer for it

Communities like his are doing their share, but Patrick pulls no punches when it comes to accountability for the climate crisis.

“What we did unknowingly up to 1988, we’re now doing knowingly. We have quadrupled our carbon footprint since 1988. Are the people who are making the money from the status quo paying their fair share in prevention and response? Absolutely not.”

Back in 1988, oil companies like Shell were already projecting that their products could double atmospheric CO2 levels in just a few decades, yet later covered that knowledge up. The harms of greenhouse gas pollution from fossil fuel expansion—their expected impact on future generations—is the reason Patrick spent years fighting the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion.

The world has now blown past the target of keeping planetary heating below 1.5 degrees. And while humanity has crossed the threshold of seven of nine planetary boundaries identified by researchers at the Stockholm Institute, there’s still time to turn things around.

Fossil fuel companies creating climate risks should pay their fair share for adaptation, mitigation, and recovery costs, says Patrick. He suggests that this kind of financial mechanism could provide homes for low-income, climate-displaced families like Serena’s that don’t have the income or collateral for loans or mortgages. Maybe it could even fund proof-of-concept builds for safe, climate-resilient houses.

Proposed by Greenpeace Canada, a B.C. Climate Recovery Fund would see the provincial government pass a law that makes major oil, gas, and coal companies help cover the skyrocketing costs of rebuilding infrastructure and protecting people from climate damage.

“It’s a truism that what you do to the land you do to yourself,” Patrick reminds me. “So, if you release too much carbon into the atmosphere, there’s going to be a day of reckoning. Big polluters have deferred the impacts onto future generations, and it is no longer about future events. It’s real, and it’s happening now, everywhere.”

Climate change is a great leveller, he adds, creating conditions like the trifecta of wind, drought and heat that turned Lytton into a tinderbox vulnerable to just one spark. These conditions will affect all of us, he warns. “I can’t tell you what, and I can’t tell you when, but it’s probably gonna involve fire, smoke, and no water.”

“My children and grandchildren deserve a chance”

Walking the land that raised him

On Nlaka’pamux territory last August, Patrick takes us across the Fraser River on a reaction ferry and onto a winding gravel road west of the town of Lytton. He wants to check if the Nickeyeah and Nohomeen creeks still have water in them.

The families around us depend on the glacier-fed creeks for water, he tells me as we ride along in his truck (Charlie trails behind us, chauffeuring our napping daughter).

Water, food, and the quiet fight to keep a future alive

“It’s getting hotter. It’s getting drier. The glaciers that are keeping these creeks alive? They’re disappearing. Drought means we’re starting to lose the surface precipitation. This is the last of the flows,” Patrick says. “Families don’t have a reliable source of drinking water anymore. They may not know it yet, but I do.”

We pull up to Nickeyeah Creek and hop out.

“Is there still water?” he calls out, almost too nervous to look.

Thankfully, there is.

Patrick is visibly elated. He grew up playing in this creek.

He launches into his hopes to build a water reservoir up on a plateau, maybe a couple of dozen feet from where the creek crosses the road. “I call it beaver ponding!” he laughs. “If you get water in the spring, you need beaver ponds. You trap the fresh water and then do timed release when it’s needed in the summer—for drinking, for irrigation, and for fire protection.” Even if water pumps go offline due to a power outage, batteries, solar pumps, or generators can provide a crucial backup when there’s still water in the tanks, he adds.

Believing that it’s possible to walk with both the traditional and contemporary ways of doing things (Mi’kmaq Elder Albert Marshall’s “two-eyed seeing”), Patrick hopes a Climate Recovery Fund could bring resiliency to Nlaka’pamux water systems. This isn’t recovery or rebuild, it’s adaptation. The community needs new ways of living with less predictable water sources.

“I’ve got 10,000 years of cellular conscious knowledge, saying this creek flowed year-round for 10,000 years, right? I know it’s coming to an end. So, there goes the surrounding ecosystem, the in-stream fish population [of rainbow trout] and you’re out of water.”

On the way to Nohomeen Creek, Patrick points out the community’s farming projects. “The people of the salmon can become the people of the potato,” he says pragmatically.

The recent increases in Chinook, coho, pink, and sockeye salmon in the Fraser River offer glimmers of hope, though Pacific salmon are in decline across most of British Columbia. Two-thirds remain below their long-term averages, including steelhead in the Fraser River, according to a 2025 report by the Pacific Salmon Foundation.

It’s a reminder of the high cost climate adaptation is asking of this community, the sacrifice required for survival. Patrick is passing on his traditional knowledge and new ways of preparing his community for a more water-scarce, food-insecure future. He wants to make sure they have everything they need to get by.

“My children and grandchildren deserve a chance,” he says.

The water is flowing at Nohomeen Creek, too.

The pain of fire, and the homes that should have been safe

It feels like a small victory here, where the Nohomeen Creek fire swept through in 2022. You can see how quickly it moved by the scorched bottoms of the remaining pines that dot the grassy fields and rolling hills.

As Patrick points out the damage from that wildfire, I try to imagine the houses that would have stood here. Some houses did survive (watering the lawn and removing vegetation from around the buildings being key variables). Other families still live in small, green temporary modular homes delivered via helicopter after the fire.

As we wind our way through the remote neighbourhood, he points out where the homes of the seven affected families once stood. “These families also want to build their homes using climate-resilient and fire-resistant materials. They never want to burn again, too.”

And Patrick is doing his best to make sure that they don’t.

Eventually, we come to the Stein River, our last stop.

At the water’s edge, learning to let go

This spot is a place people come to do medicinal baths. With the cold, crystalline water beckoning ahead, I can imagine why.

“Sometimes you just need to let stuff go,” Patrick says. “You can ask the wind, smudge, soil or you can ask the water to take it away.”

Patrick remembers coming to the Stein in 2022 after the Nohomeen Creek wildfire. “I sat down here and I wept for the families because, you know, that was re-traumatizing. They survived the Lytton 2021 fire, and had to listen to the screams and the smashing and the bangs and stuff, and the next year it happened to them.”

With the water reservoirs on the Nohomeen and Nickeyeah Creeks and by supporting them to make their homes defensible against wildfires, he and the LFN want to “give these families something good.”

The water takes care of people, but it also needs to be taken care of. Within eyesight is a water gauge, which LFN recently installed to help assess water quantity. The 24/7 data it relays details how much water is flowing, its temperature, and any suspended particulates. It’s what Patrick wants to do for the Nohomeen and Nickeyeah Creeks (and all LFN surface water), too.

When the flame flickers, faith becomes a daily choice

Staying optimistic isn’t always easy, even for an eternal flame of optimism. But hope flows from action.

On the bench lands above us, Patrick points out where Nlaka’pamux ancestors built pit houses, traditional log-framed buildings built partially underground to stay cool in the intense summer heat and warm in the winter. Because they were covered in dirt, they didn’t burn when a fire passed through.

“Our ancestors knew what to do back then, and I struggle today to try and understand why it’s so hard to go back to ways that worked.”

That flame is flickering,” Patrick admits. “It’s getting harder and harder to pick myself up … I’m afraid for my wife, I’m afraid for my grandchildren, and I’m afraid for Canadians. But I won’t let fear paralyze or define me.

It’s like he told Sarika Cullis-Suzuki, he remembers, “Our children’s futures aren’t pre-determined. It’s what you say and do today that’s what matters.”

A moment passes. Then, with characteristic enthusiasm, he turns to me with a wry smile, arms raised.

“So what do we do? How do we maintain the faith? How do we Jon Bon Jovi this shit?” (a reference to the band’s 1992 song “Keep the Faith”).

His answer?

“By taking care of business.” (The immortal personal mantra of one Elvis Presley).

That’s the real clarity I have leaving our conversation: just do something. Anything.

Then do the next thing.

The ‘why’ is clear. With my daughter freshly awake from her long nap and now scrambling over the rocks around us, I feel my own mettle strengthening. Finish this article amid the many joys and pressures of everyday life. Then, do the next thing—something to keep the fossil fuels in the ground, to prepare my communities to be more resilient, to leave this place safer for her generation and the ones to come.

We’re still here

We’re still here, and that still matters

As Charlie, Meroë, and I leave Lytton, the wind sweeping through the Fraser Canyon behind us, I find myself dwelling on our time by the Stein.

“By being me, I penetrate the noise, right?” Patrick had said, musing over his disarming, rapid-fire and irreverent way of communicating. The sound of the river behind him was a steady roar. “You know why our ancestors lived up there [on the bench lands]? Because if they stayed right here, they wouldn’t have heard predators, invaders or a flood. You had to get away from the noise that prevents you from being safe.”

Noise like the misinformation from fossil fuel companies and politicians who downplay the risks of oil and gas, or Silicon Valley’s social media algorithms that anger, divide, and distract us.

“The worst-case scenarios that we forecasted starting 15 years ago are occurring now. Faster than we ever imagined,” Patrick warns. “We are facing a world of hurt, and it’s not too late to change our ways. We’re hardwired to adapt. Together, we are going to be ok. There’s still time. ”

It’s this sense of purpose and ethos of rolling up our sleeves to collectively do what must be done that characterizes “hope flows from action”. He isn’t naively optimistic, but he knows the future isn’t set in stone.

Patrick does what he does because there are still current and future generations to hope for, and because (as he often says) he still has “Creator’s gifts of life and choice.” Today, he laughs, he will do good things “until he mucks it up.”

His optimism isn’t just a personality trait. It’s a decision he wakes up and makes every day. That’s the takeaway.

As Patrick speaks, a salmon leaps out of the river behind him—a last dance, a show of hearty defiance, or perhaps simply because it’s still here and still can. You choose.

***

With gratitude to Patrick Michell for his time out on Nlaka’pamux territory and his stories, knowledge and heart.

This article has condensed conversations from August to November 2025 for sake of clarity and brevity.