Let’s start off by being realistic: it’s probably safe to say that the coronavirus pandemic won’t come to an end in 14 days.

For the last ten days, most of us have been spending a great deal of time glued to our screens, scrolling through our social media accounts (we’re social animals, after all!), all the while respecting the directives of public health authorities. We’ve been consuming, absorbing, and sharing article after article, knee-slapper joke after knee-slapper joke, and dank meme after dank meme… In short, the flow of information has been dense, constant and fast. It’s been pouring out of everywhere! In response — and for some of us, in an effort to calm our anxiety — we’ve lapped it up, unfortunately sometimes resorting to diagonal reading in the process. Thus, given the extent of misinformation about COVID-19, one might ask: are we sharing smartly?

Even if a lot of articles aim to inform their audience, fake news (also referred to as yellow journalism, sensationalism) is still rampant and hard at work to mislead us.

| Interesting fact: Fake news, on average, spreads faster and more widely than accurate news, according to Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) researchers. |

Though not exclusive to this kind of content, fake news is often characterized by its tendency to provoke emotional reactions in situations of widespread uncertainty, like the one we are currently facing with COVID-19. And what can we say when a real person — let’s say a friend we know personally — unconsciously or unintentionally shares fake news? For a brief second, because of our relationship with the sharer, the information might seem to take on a bit more credibility in our eyes. And all this makes it harder for us to properly engage with it. But if the last few days have taught us anything, it’s that we’ve got a responsibility to do so. So let’s seriously ask ourselves: do I know how to spot deceptive content? How do I verify it? Would it be right to share it?

As we answer these questions below, remember: t no one is safe from fake news , but together, if we take our role as Internet users and consumers of information online seriously, we can go some ways to seeing the truth prevail.

Can we have specific examples?

Do you remember how much fake news was spread during the American elections, especially on Facebook? Deceptive news articles were shared even more widely than articles from credible newspapers, like the New York Times or the Washington Post. Between February and D-Day in August 2016, the reach of ‘mainstream’ news (TV, radio, print) dwindled from 12 million to 7.3 million readers, while the reach of fake news on Facebook jumped from 3 million to 8.7 million readers).

This is why some say that ‘to reduce fake news to the status of mere ‘false news’ is to ignore the unprecedented nature of social networks, which are capable of massively and continuously contaminating the public space’ (Source – FR only).

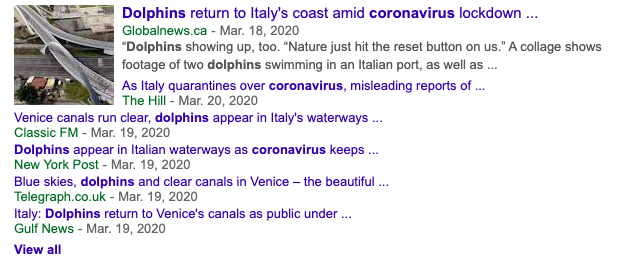

Within days of COVID-19 taking us by surprise, we saw claims of all sorts (and their counters!) come out of the woodwork… and get shared! They ranged from “Eat garlic”, “gargle in salt water (be careful, it should be hot not warm)”, “drink water every fifteen minutes”, “shoes transmit the virus”, and “dolphins are back in Venice”… Well, it turns out that each one of these claims is false!

As you can see, the claim about Venice dolphins, in particular, travelled around the world. Presented in terms of the benefits of our social isolation, it was picked up by otherwise presumably credible international and Canadian media (not unlike this polar bear story in 2017). However, the story’s popularity does not make it any more true. Unfortunately, the damage done by the wide publication of this story could not be undone by the comparatively few sources (Euronews, National Geographic) that took the time to set the record straight.

So, how can we separate fact from fiction?

On the one hand, we need to place value on fact-checking in journalism.

There are specialized journalists who take the time to demystify widely circulating claims and, above all, correct the record. Especially now, when getting things right can be a matter of health and serious illness, consider taking a look at this non-exhaustive, bilingual list of news sources that have strong fact-checking reputations. You can consult these in addition to the Health sections of your favourite newspapers or magazines:

- Les Décrypteurs from Radio-Canada: they confirm that misinformation about the coronavirus has reached levels never before seen for a pandemic. Add to that the CBC News Investigates section.

- Radio-Canada’s journalism lab, RAD, is more suitable for those with teenagers at home.

- CBC Marketplace, for those interested in economic impact and benchmarking, is particularly useful.

- There are also two fact-checking search engines: Fact Scan and Snopes.

- Coming: Centre Déclic which, in collaboration with the newspapers of the “Coopérative nationale de l’information indépendante” and “Québec Science”, is set to create a dialogue between scientists and members of the public.

On the other hand, we need to place value on fact-checking in non-journalistic sources of information. Credible non-journalistic sources include:

- International organizations such as the World Health Organization, which has released a myth busters fact sheet.

- The official website of the government, e.g. Health Canada.

- The Canadian government has also published a fact sheet about online misinformation, which is available to everyone seeking to critically evaluate the legitimacy of online information.

5 easy steps to spot fake news

The National Observer (a credible source of information, don’t worry!) has released an easy five-step guide to identify fake news:

Let’s reduce the flow of fake news all together!

– THE END –