Three recent developments highlight how the Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX) pipeline is a white elephant in a world that is even modestly moving away from fossil fuels. Together, they offer the Trudeau government a graceful exit from the controversial project.

They should take it.

The Parliamentary Budget Office report

In its December 8 update on the financial and economic considerations related to the Trans Mountain pipeline, the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) found that even modest new climate policies (that reduce the demand for oil) could turn the TMX pipeline into a money-loser. It found that “the profitability of the Trans Mountain assets is highly contingent on the climate policy stance of the federal government. Consistent with modelling from the Canada Energy Regulator (CER), if policy action on climate change continues to become more stringent, it is possible for the Trans Mountain assets to have a negative net present value.”

In short, the TMX pipeline only makes economic sense in a world that is utterly failing to tackle climate change. To explore this further, it is worth reviewing the CER report that the PBO builds on, as well as Kinder Morgan’s securities filings prior to the pipeline being nationalized.

The Canadian Energy Regulator’s Energy Future report

The PBO report builds on the November 24 Canada’s Energy Future 2020 report from the Canadian Energy Regulator (CER) that explored two possible futures. In the first (“Reference”) scenario, there are no new climate policies adopted anywhere in the world and the Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX) pipeline would be needed to meet a modestly growing oil demand (the dotted black line in the graph below taken from the CER’s Energy Future report). That seems unlikely, given that Canada, the European Union, Japan and China have all pledged to transition off of fossil fuels and a Biden-led U.S. will soon join them.

In the second possible future (called the “Evolving” scenario), there are modest new climate policies, but these measures are still not stringent enough for Canada to meet either its existing 2030 or 2050 greenhouse gas reduction targets (see the “Does the Evolving Scenario Meet Canada’s Climate Commitments?” box on page 62). This is the actual business-as-usual scenario, yet even with these kinds of modest climate measures, the CER predicts that global oil demand will be too low for either the Trans Mountain Expansion or Keystone XL pipelines to be needed (the pink dotted line, below).

The oil industry will argue that it is always good to have extra capacity, but this is the business-as-usual scenario and almost certainly overestimates future oil demand. As Dr Hasting-Simons has noted, it also entails an assumption that Canada doubles or triples its share of global oil production, which is unlikely given the recent trend of investment fleeing the carbon-intensive oil sands.

Net-Zero Legislation and Climate Risk

The other significant recent development – the tabling of the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act in the House of Commons – could ultimately prove to be an even sharper thorn in the government’s side on TMX.

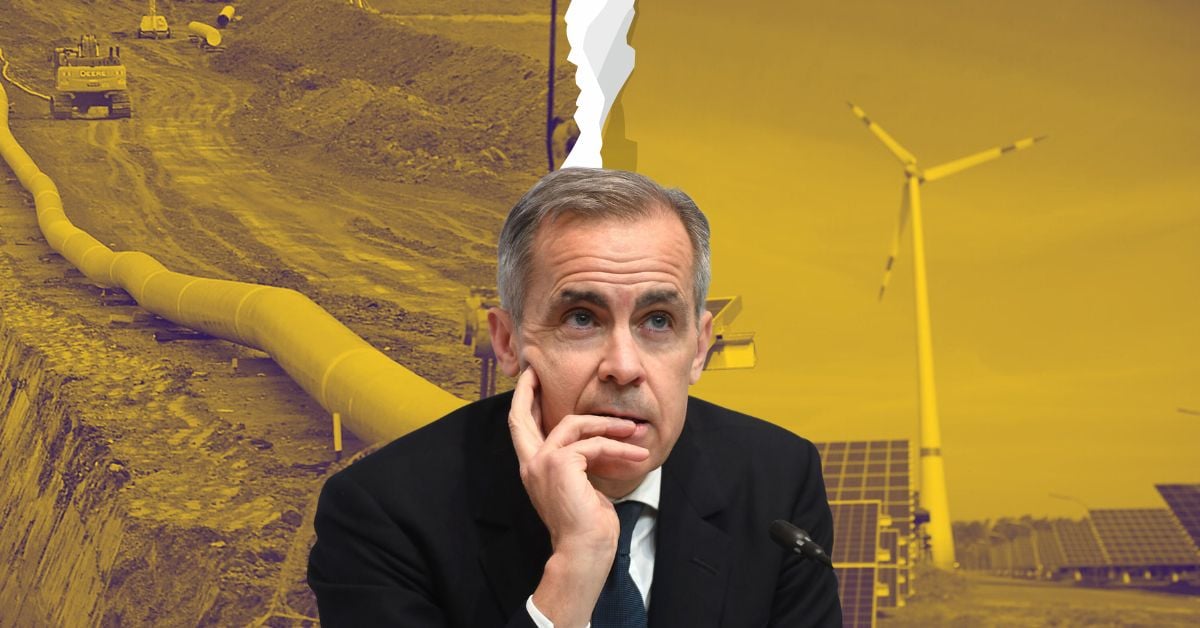

Buried in the bill is a requirement for the Government of Canada to publish an annual report describing how departments and Crown corporations are considering the financial risks and opportunities of climate change in their decision-making. This kind of climate risk reporting has been championed by former Governor of the Bank of Canada Mark Carney and will soon be mandatory for large companies in the UK. The Trudeau government made climate risk reporting a requirement for accessing some of its covid-19 loan programs and the Bank of Canada is doing the scenario-planning work that would be required to make it mandatory for federally-regulated banks.

In 2017, Greenpeace Canada challenged the initial sale of shares in the newly-created company Kinder Morgan Canada, whose major asset was the Trans Mountain pipeline. We did it on the grounds of inadequate disclosure of climate risks, including that the company may have used outdated oil demand projections which could potentially mislead investors by portraying an overly optimistic view of the international oil market (see the full complaint for details).

Kinder Morgan subsequently amended their prospectus (bolded sections below) to acknowledge that meeting the decarbonization targets set out in the Paris Agreement could reduce oil demand so much that the pipeline’s shippers wouldn’t be able to pay their bills:

“Changes in the business environment, an increase in production costs, supply disruptions, or higher development costs, could result in a slowing of supply to the pipelines, terminals and other assets of the Business. In addition, changes in the overall demand for hydrocarbons, the regulatory environment or applicable governmental policies (including in relation to climate change or other environmental concerns) may have a negative impact on the supply of crude oil and other products. In recent years, a number of initiatives and regulatory changes relating to reducing GHG emissions have been undertaken by federal, provincial, state and municipal governments and oil and gas industry participants (including, for example, the decarbonization targets set forth in the Paris Agreement). In addition, emerging technologies and public opinion has resulted in an increased demand for energy provided from renewable energy sources rather than fossil fuels. These factors could not only result in increased costs for producers of hydrocarbons but also an overall decrease in the global demand for hydrocarbons. Each of the foregoing could negatively impact the Business directly as well as the customers of the Business that are shipping through its pipelines or using its terminals, which in turn could negatively impact the prospects of new contracts for transportation or terminalling, renewals of existing contracts or the ability of the Business’ customers and shippers to honour their contractual commitments” [emphasis added] (pages 34-35 of the prospectus).

The securities challenge became moot, however, once Kinder Morgan backed out of the project and the Trudeau government stepped in to buy it. The Crown corporation that now owns the pipeline doesn’t have to file reports with securities regulators or answer to shareholders at Annual General Meetings.

Greenpeace Canada wrote to then-Finance Minister Bill Morneau in November 2018, asking him to undertake a climate risk assessment of the Trans Mountain Expansion pipeline. We never got an answer.

But now we might. If the federal net-zero legislation is passed with the climate risk disclosure requirement intact, we may finally see the government forced to justify a project that even its own energy regulator says only makes sense in a world where no one is acting on climate change.

And that could provide an off-ramp for a government looking at ever-rising construction costs and ongoing opposition to construction that will heat up once covid-19 restrictions are lifted.

It is worth recalling that the Trudeau government’s initial approval of TMX was framed as a quid pro quo for Alberta’s support of the federal government’s climate plan. In his 2016 speech announcing the approval, the Prime MInister said: “We could not have approved this project without the leadership of Premier Notley, and Alberta’s Climate Leadership Plan – a plan that commits to pricing carbon and capping oilsands emissions at 100 megatonnes per year.”

Under Premier Kenney, Alberta has abandoned those commitments and is even fighting the federal carbon tax in court. Hence there is no climate “quid” for an increasingly expensive pipeline “quo.”

Spending $12.6B+ on an unnecessary pipeline will be hard to justify when those resources could be better spent on the promised national child care, pharmacare or green recovery investments.