In a development worthy of its own true-crime podcast, the United Nations’ net zero banking alliance was murdered and Canadian banks’ fingerprints are all over the murder weapon. Thankfully, the UN isn’t taking this lying down and has struck back.

The ultimate lesson of this tragic tale is that since the banks won’t, or maybe can’t, get serious about decarbonization on their own, then governments will have to make them do it. But there are some interesting twists along the way.

The push for science-based criteria

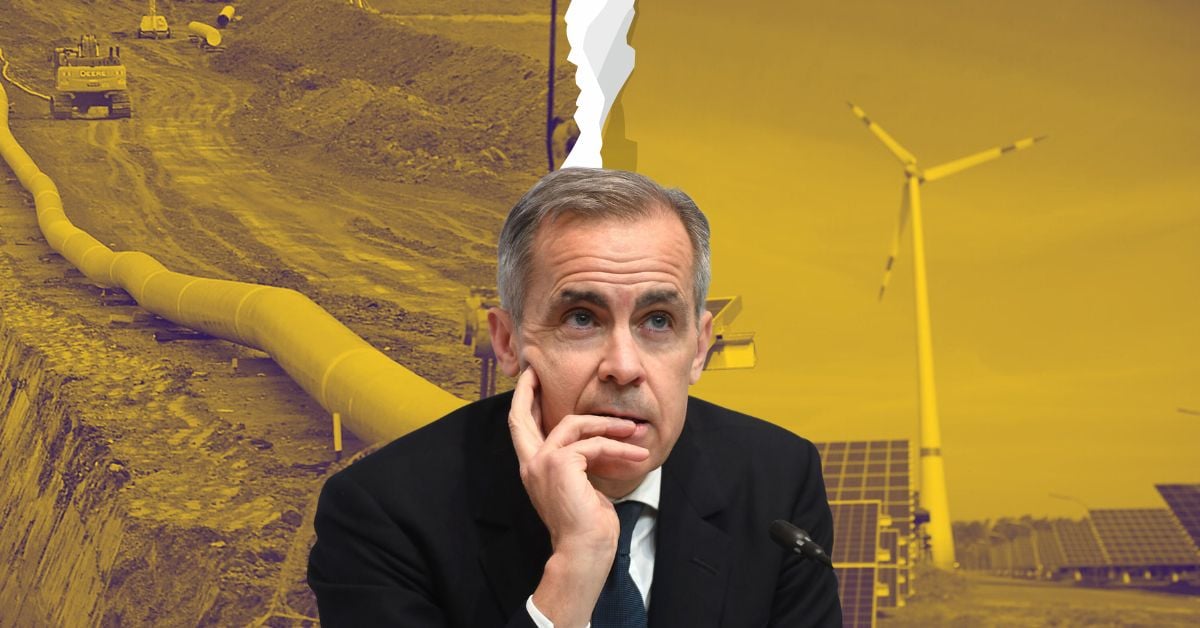

One year ago, Canada’s big five banks belatedly joined the Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA), which is part of the the UN-sponsored and Mark Carney-led Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). By joining, they committed to aligning their loans, investments and underwriting activities with achieving net zero emissions by 2050. Yet collectively, those same five banks increased their 2021 funding for fossil fuels by 70% relative to the year before and are all among the top 20 global banks funding oil, coal and gas.

Frustrated by this kind of greenwash (which was not unique to Canadian banks), the UN umbrella group that sets criteria for GFANZ and similar initiatives by non-state actors (Race to Zero) clarified their expectations of members in June 2022. Saying that they were making explicit what had always been implicit, Race to Zero published a new interpretation guide for membership. To remain as members, financial institutions must:

- “Phase down and out” support for unabated fossil fuels as part of a global, just transition. The speed with which this happens should be in line with a science-based scenario like the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero Scenario (which precludes any investments in new fossil fuel fields). As part of this, they called for an immediate moratorium on funding new coal projects.

- Set an interim target for financed emissions that reflects maximum effort toward or beyond a fair share of 50% global reduction in CO2 by 2030.

- Include full lifecycle (i.e. scopes 1-3) and all sources (i.e. portfolio, financed, facilitated and insured) of emissions when setting targets.

- Align their public relations and lobbying activities with net zero.

Greenpeace Canada published the Racing to Zero? report in August showing that Canadian banks were far from meeting this target, and urged them to accelerate their decarbonization strategies rather than lobbying against the UN criteria.

The banks chose to push back.

Banks threaten to leave

It started with anonymous sources at three big U.S. banks telling the Financial Times that they were considering pulling out of the Net Zero Banking Alliance (and thereby out of GFANZ). According to the report, “some of the most significant members of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero have said they feel blindsided by tougher UN climate criteria and are worried about the legal risks of participation.” One senior executive was quoted as saying “What if we get it wrong, make a mistake or someone lies? Then the bank can be sued, that is an unacceptable risk.”

Anonymous sources at Canadian banks were soon telling the Globe and Mail that they were also considering leaving GFANZ, though they would only do so if other banks did as well.

This campaign of leaks from anonymous sources was clearly designed to put pressure on Race to Zero to back off from the new criteria.

Or else.

The pushback: science-based criteria

Their concerns, the bankers claimed, were two-fold: the new criteria were too strict and potentially exposed them to legal risk.

On the former, they felt that the UN had moved the goalposts by making the implicit expectations explicit. How the bankers thought they could continue to pour billions into fossil fuel expansion projects and still claim they are on a path to zero carbon has never been adequately explained, but they really didn’t like being asked to prove it.

One possible explanation is that they joined GFANZ primarily as a public relations move designed to send a message to the public, investors and government regulators that they are serious about climate action, but without consequences for inaction.

This is a story that we have seen play out many times before, where an industry under pressure over pollution sets up a voluntary initiative to prevent government regulation. It was pioneered by the Canadian chemical industry when they created the Responsible Care program to fend off demands for tighter regulation in the aftermath of the deadly 1984 Bhopal disaster and replicated in the climate space by the Voluntary Challenge Registry in the 1990s.

This time, however, the UN called the bankers’ bluff. Rather than letting the companies decide whether or not they were doing ‘enough’, they set clear milestones. And if companies didn’t meet them, they faced a real (and embarrassing) possibility of being kicked out.

In response, the bankers sharpened their knives.

The pushback: Fossil fuels strike back at ESG

The other complaint about the UN criteria focused on the possibility that they could run afoul of antitrust legislation. The co-chair of the UN’s Race to Zero advisory panel, Oxford professor Thomas Hale, was shocked to learn that he could be sued personally for “simply being explicit that expanding coal production is not a part of any credible scientific scenarios to achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement.”

The threat here is to sue financial players – and/or members of the UN advisory panel – for ‘colluding’ against coal, oil or gas.

This threat is part of a broader strategy. As corporate ESG (environment, social and governance) commitments have come closer to being codified in law – like the push to have climate disclosure become mandatory – they have come under increasing attack. Recently, the New York Times did an in-depth investigation that drew on over 10,000 documents to detail how the same dark money, fossil fuel-funded groups that used to fund the climate denial campaigns are now weaponizing Republican state treasurers to go after banks or investors who restrict funding to oil, coal or gas.

We have seen indications this is taking hold in Canada as well. Former Alberta Premier Jason Kenney cut the Government of Alberta’s ties with HSBC over its tar sands ‘boycott.’ In late August 2022, the right-wing Fraser Institute added an anti-ESG page to their website and launched a series of publications on how ESG is an affront to capitalism and/or freedom. Also in late August, the Conservative-linked Canada Proud organization dropped over $9,000 on a series of anti-ESG Facebook and Instagram ads (like this and this).

That legal risk was unlikely to be realized, however, as Race to Zero tweaked the wording of their criteria in mid-September to preempt legal action. The threat had, however, resulted in weaker criteria that provided greater leeway to the banks to choose their own path towards net zero.

But it was already too late.

The murder

On October 27, GFANZ announced that it was cutting ties with the UN Race to Zero, stating “member alliances are encouraged, but not required, to partner with the Race to Zero.” This effectively makes the banks themselves the judge and jury on whether they are net zero-aligned.

GFANZ – as a science-based, third party verified initiative – was dead. Through their threat to pull out, Canadian banks were part of killing it.

The UN Secretary General was not impressed. On October 29th, António Guterres subtweeted GFANZ members: “Climate commitments to net zero are worth zero without the plans, policies and actions to back it up. Our world cannot afford any more greenwashing, fake movers or late movers.”

At the climate negotiations in Egypt, the UN’s High-Level Expert Group on the Net Zero Emissions Commitments Of Non-State Entities (which is chaired by Canada’s former Environment Minister Catherine McKenna) put out a report denouncing this kind of “greenwash.” While reiterating all of the Race to Zero criteria, the report stressed that “Net zero is entirely incompatible with continued investment in fossil fuels.”

In launching the report, Guterres added that “the message is clear to all those managing existing voluntary initiatives. Abide by this standard and update your guidelines right away — and certainly no later than COP28.”

In case that was too subtle, McKenna told the Financial Times that “there are some companies, in particular financial institutions, that don’t understand that when you make a net zero commitment it means something.”

What’s next?

Even under the best of circumstances, voluntary programs are going to be weak because there is no credible threat of enforcement. In a world where fossil fuel interests are weaponizing laws and politicians against climate action, they are likely useless.

Race to Zero’s co-chair Thomas Hale summed it up well:

“First, as climate politics get existential, the battle over corporate climate action is going to get more intense. Vested interests are pushing back, hard. Hiding behind flimsy legal pretext will not work. Companies with fuzzy net zero targets, trying to keep both sides happy, will be in the crosshairs. Clarity and rigour are needed.

Two, the rules governing the economy need to catch up to our climate goals. The fact that anti-competition law, created to safeguard the public interest, could be manipulated to work against it shows the need for urgent reform. Credible voluntary action builds momentum for these changes, but regulators need to step up.”

McKenna’s UN High Level Working Group echoed this point:

“To effectively tackle greenwashing and ensure a level playing field, non state actors need to move from voluntary initiatives to regulated requirements for net zero. Verification and enforcement in the voluntary space is challenging. Many large non-state actors— especially privately held companies and state-owned enterprises —have not yet made net zero commitments which raises competitiveness concerns. This picture is changing fast, but it still requires the resolve of governments and regulators to level up the global playing field. This is why we call for regulation starting with large corporate emitters including assurance on their net zero pledges and mandatory annual progress reporting.”

By breaking ties with the UN, GFANZ has made it crystal clear that national governments must set rules to force bankers to do what they can’t or won’t on their own: align their loan and investment strategies with a zero-carbon world.

Fortunately, the federal bank regulator in Canada is in the process of establishing regulations on climate finance. Canadian environmental groups have published a Roadmap to a Sustainable Financial System in Canada and federal Ministers Guilbeault and Wilkinson have indicated they are prepared to bring in new climate finance rules.

The banks won the first round, but by killing GFANZ they may have summoned a new sheriff to town.

Discussion

Peak Spire is a Toronto, Ontario based company that provides Web Development, UI/UX design, App Development services. https://peakspire.ca/

It's a quite nice blog. Pure Mart is a newly Canadian online store striving to keep you healthy.We are bringing you all your favorite healthy food & snacks and the best healthy alternatives to achieve your fitness goals, pretty much in one place. Enjoy our range of products that help you to get fit and guilt free. https://www.puremart.ca/