In the flurry of election and tariff chaos, the Liberal party recently announced a new housing plan promising to build green and affordable homes, quickly.

No matter who is elected this spring, climate experts are rightly pointing out that any national housing strategy should have requirements for low-carbon heating, among other efficiencies to meet the federal government’s climate-reduction commitments.

What hasn’t entered the discourse yet, is that sustainable home building doesn’t stop at the doorstep. New communities can be built in ways that ensure they include biodiverse and ecologically appropriate greenspaces instead of turfgrass lawns that can require incredible amounts of time, energy, water, and petro-chemical pesticides to stay alive.

Intentionally encouraging biodiverse residential landscapes in tandem with a national housing strategy could provide one of many pathways for the federal government to contribute to its international commitments under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework and its goal of protecting 30 percent of lands and waters by 2030.

In many parts of Canada, lawns are composed of a mixture of grasses, and primarily consist of Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis), a non-native species brought to the continent by European settlers. The idea of a lawn itself is rooted in classist and colonial history, where only the rich had the money and resources to maintain such a labour-intensive landscape.

Lawn culture is perpetuated in many parts of Canada through archaic municipal “grass and weeds” by-laws that put barriers in the way of residents who wish to grow natural and biodiverse gardens, and by default encourage non-native, monoculture, turfgrass lawns. These municipal by-laws often include arbitrary language, using subjective words like “unsightly” to limit what residents can grow and prop up the outdated legacy of lawns. In some cases, residential gardeners are having to take legal action to uphold their right to a natural or native plant garden.

Luckily, there is strong momentum to put a stop to these nonsensical laws. Last year, a coalition including the Ecological Design Lab at Toronto Metropolitan University, David Suzuki Foundation, Canadian Society of Landscape Architects (CSLA), Canadian Wildlife Federation (CWF), and author and activist Lorraine Johnson, published an open letter to Canadian municipalities, launching an initiative advocating for municipal bylaw reform to remove barriers to growing biodiverse gardens in municipalities across the country.

Gardens with a diversity of species including native plants make great sense and offer all kinds of benefits, from supporting pollinators and local ecosystems, to reducing maintenance costs and time. Planting species that are native to your local ecozone and ecosystem enhances resilience at a time when climate change is having negative impacts on natural systems. Moreover, native and natural gardens are beautiful and they play an indelible role in supporting local biodiversity.

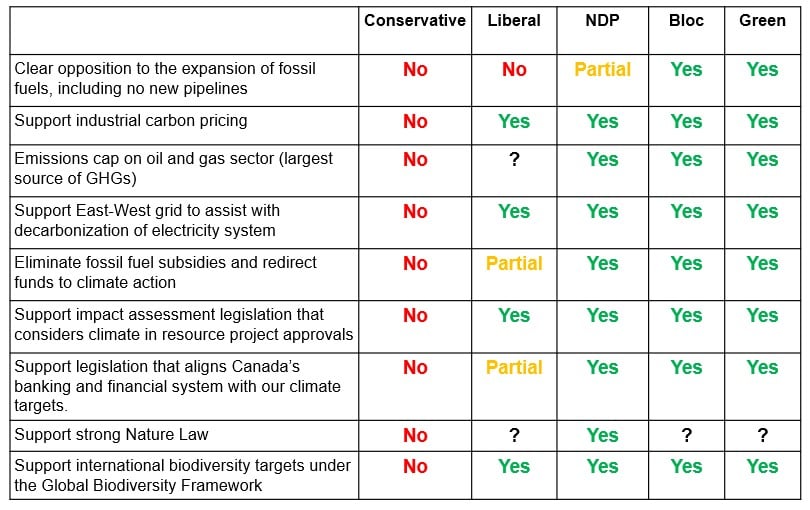

At the federal level, we saw progress on implementing a national strategy to address our commitments under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. The Nature Accountability Act (Bill C-73) was introduced last June and made it to pre-study when the election was called, parliament prorogued, and everything came to a standstill. Indigenous leaders and environmental groups have been advocating for the law to respect Indigenous sovereignty and to include clear targets and accountability measures. A law like this has the potential to protect large areas of Canada’s land and waters while centering Indigenous rights and land stewardship.

We look forward to working with the next government to implement a strong federal nature law. But municipalities don’t have to wait for this election outcome to make a difference. They can get moving to advance bylaw reform in support of biodiversity and do their part for nature protection across Canada right now.

—–

Farrah Khan is a strategy consultant with Greenpeace Canada and a sustainable landscape designer based in Toronto.

Lorraine Johnson is the author of numerous books on tending the earth, including A Garden for the Rusty-Patched Bumblebee, co-authored with Sheila Colla.