The political response to the climate emergency is the defining issue of our time. But progress has been painfully slow. The European Union has staked its credibility on showing the world that it can decarbonise as extensively as science demands, while ensuring no-one is left behind. The European Commission claims its new climate law – the centrepiece of the European Green Deal – will be at the heart of this effort. But questions remain about the law’s ability to commit governments to urgent action.

Greenpeace EU climate policy adviser Sebastian Mang: “The problem with the EU’s response to the climate emergency is that what it calls politically unprecedented is in fact woefully insufficient when you look at the science and the scale of the challenge. Decades of dithering, delays and half-baked measures have led us to a point where the very survival of life on Earth is at risk. But instead of taking responsibility, governments and corporations are deflecting urgent action by latching on to distant targets that primarily commit future generations.”

Since her appointment, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen has been adamant that responding to the climate and ecological emergency is the most pressing issue facing the EU. She promised a European Green Deal in the Commission’s first 100 days, with a new EU climate law at the heart of it.

When it was released in December 2019, the European Green Deal promised much, but left the Commission with a lot to prove. On 4 March, von der Leyen and Commission vice president Frans Timmermans will unveil the draft EU climate law amid much fanfare.

This briefing outlines expectations for the new law, within the context of the green deal’s ambition to respond to the escalating climate emergency.

The European Parliament and national governments are expected to battle it out this year to amend the Commission’s draft. The chair of the European Parliament’s environment committee, Pascal Canfin, is keen to rush through the final climate law before a UN climate conference in November. But central and eastern European governments, led by Poland, could try to drag out the process and are expected to resist binding short-term measures.

FLIMSY CLIMATE LAW

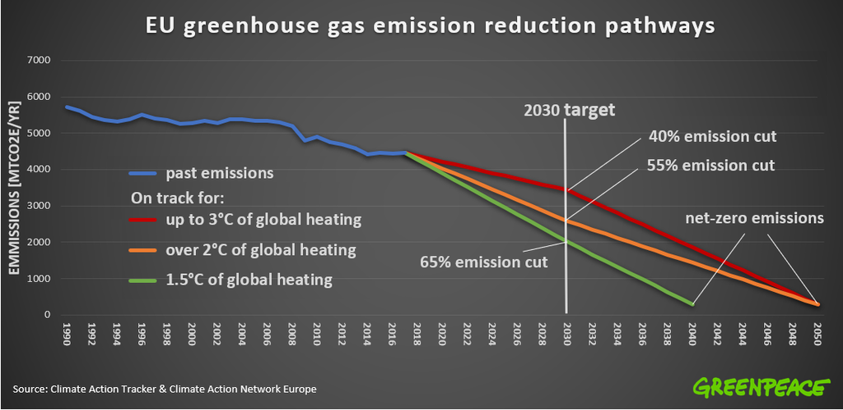

The Commission’s draft is likely to largely focus on a target to reduce EU greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by 2050. The Commission is also expected to suggest giving itself the power to raise emission targets, leaving governments and the European Parliament with limited power to object. These reviews would take place every five years – but only after 2030 – and be guided by the best available UN climate science.

The Commission has said that it would not table an upgraded 2030 climate target until September, after it has carried out an impact assessment.

The draft law is also expected to set out principles or guidelines to encourage the alignment of other EU policies with its climate targets. The scope of these guidelines and whether any of them will be binding is as yet unknown. Timmermans has said that ensuring “joined-up thinking […] and consistency” is likely to be an essential but “complicated task.”

In addition, the Commission is expected to require governments to develop and implement plans to adapt to climate impacts.

In practice, the expectation in Brussels is that the draft EU climate law will be thin on substance, compared to most equivalent laws at the national level.

It is unlikely, for example, that it will include plans to phase out subsidies for fossil fuels and other climate-damaging sectors, such as airlines and industrial agriculture. The EU and several European governments committed ten years ago at the G20 to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies by 2025. Despite this, no EU government has a plan to phase out fossil fuel subsidies, and the lion’s share of the EU’s budget, including the recently tabled Sustainable Investment Plan, continues to allow investments into gas, nuclear energy and industrial agriculture. EU governments provided on average €55 billion per year in fossil fuel subsidies between 2014 and 2016, according to research for the Commission.

The new draft climate law will also fail to address the political influence and greenwashing of the fossil fuel industry.

To stimulate more immediate government action, environmental organisationshave called for a much broader set of measures, including intermediate climate targets, in particular an upgraded EU 2030 target, the end of fossil fuel subsidies, and regular checks to assess progress against the latest climate science. In line with existing national climate laws, NGOs also say the EU’s targets and policies should be regularly reviewed by a new independent body of climate scientists and other experts.

Another missing element will be a recognition of the growing impact of animal farming on the EU’s greenhouse gases, now accounting for a share of 12-17%. Greenpeace has called for measures and a target to reduce the EU’s overconsumption of meat and dairy products, which are major contributors to climate breakdown, as well as deforestation and ecosystem destruction.

Finally, in order to achieve full transport decarbonisation by 2040, Greenpeace has called for the phase out of new petrol and diesel cars by 2028, This target should be included in the law and combined with measures to accelerate the modal shift from cars and planes to alternatives like walking, cycling, train travel and public transport.

POLITICAL BATTLE LINES

The European Parliament also has its doubts about an EU climate law primarily built around the net-zero target. In a resolution on the European Green Deal in January 2020, the Parliament said the EU should cut emissions by 55% by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels) and set an “intermediate” target for 2040, with the aim of achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

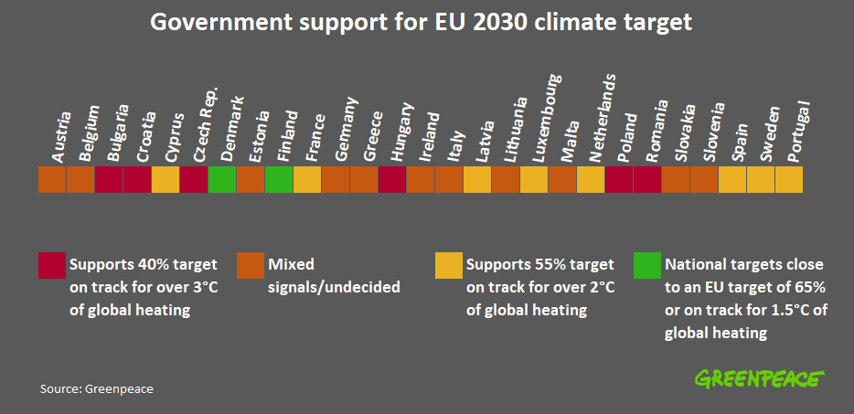

The European United Left and European Greens support targets of 70% and 65% respectively. These targets are in line with limiting global heating to 1.5°C, which scientists say would rein in the worst effects of climate breakdown. Although a majority of MEPs from the Socialists and Democrats group abstained on votes on the higher targets, the group as a whole supports a target of 55%, which would result in over 2°C of heating and widespread climate breakdown. The majority of the Renew group also favours the 55% target.

The majority of the European People’s Party supports a target of 50% by 2030. Most of the European Conservatives and Reformists group and most of the far right Identity and Democracy group voted against a 2030 target increase.

The EU’s current target for 2030 is to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 40%, which is incompatible with commitments made under the Paris climate agreement and would result in around 3°C of global heating.

The Socialists and Democrats group and the European Greens have also called for the climate law to offer more than just climate targets. For example, they call for a scientific advisory body to make sure EU policy is in line with climate goals, and are keen that the most disadvantaged people in society do not shoulder the burden of a ‘green’ transition. The European Greens also call for an end to all fossil fuel subsidies by 2021.

CLIMATE FINANCE

The Commission’s €1 trillion European Green Deal Investment Plan (or Sustainable Investment Plan), released in January, was the first initiative under the European Green Deal. The Investment plan will cover a ten-year period between 2021 and 2030 with investments of €100 billion a year.

According to the Bruegel think tank, the European Green Deal would in fact require three times more investments.

The investment plan is intended to help the EU achieve the 2050 net-zero target and is made up of €503 billion from the EU budget, which the Commission says will trigger €114 billion in national co-financing and leverage around €279 billion of private and public investments.

As part of the Sustainable Investment Plan, the Just Transition Mechanism, worth another €100 billion between 2021 and 2027, is meant to support the EU regions currently most reliant on fossil fuels. Only a small part of the Just Transition Mechanism, known as the Just Transition Fund, worth €7.5 billion in public EU money for seven years, has entirely excluded funding for fossil fuels, like gas, and for nuclear energy.

Environmental groups argue that the Sustainable Investment Plan and the entire EU budget should exclude fossil fuel and nuclear subsidies. Greenpeace has also called for the EU to limit access to the Sustainable Investment Plan to countries committed to a coal phase out by 2030 and a fossil fuel phase out by 2040.

The Commission has labelled 40% of all payments under the Common Agricultural Policy as green. This represents roughly €130 billion under the next EU budget (according to the latest plans). With a poor track record for ‘greening’ measures and governments largely in charge of how to spend the money, the European Court of Auditors has slammed the claim that these funds will be used to fight climate change as “unrealistic.”

CLIMATE POLITICS

Under the Paris climate agreement, governments must submit new or updated 2030 climate plans before the UN conference, in line with the objective to limit global heating to as close as possible to 1.5°C.

By failing to include a 2030 emission reduction target in the EU climate law and by delaying a plan to raise this target until after the summer, the European Commission could derail the prospects of a global climate deal at the end of the year. There is a very real risk that the EU could go empty handed to the UN climate conference in Glasgow this November.

So far, only three governments, Norway, Suriname and the Marshall Islands, have submitted new or updated plans, while 134 countries, including the EU, have stated their intention to do so in 2020. The likes of China and India, who have not formally committed to increase their targets, are unlikely to pledge to step up climate action without major developed blocs like the EU taking the lead by agreeing to higher targets first.

In September, Chinese President Xi Jinping will meet EU and national leaders in Leipzig, Germany, for an EU-China summit. The climate crisis is already on the agenda. This would be the ideal moment for a joint announcement on climate commitments ahead of the UN conference. The EU and China are responsible for close to 40% of all global emissions.

In a recent resolution, the European Parliament also underlined the need for a speedy agreement to raise the current 2030 target in line with climate science and the Paris climate agreement “well ahead” of the EU-China summit.

The European Parliament, Commission president von der Leyen and several EU governments – France, Spain, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Luxembourg and Latvia – have said the EU should increase its 2030 climate target to 55%. German chancellor Angela Merkel has indicated that she could support this, but her government has not yet adopted a formal position.

The Danish and Finnish government’s national climate targets, if fully implemented, are already much stronger than what an EU 55% target would require from them, with Denmark committed to a 70% cut in emission by 2030 (below 1990 levels) and Finland heading for net zero emissions by 2035.

Ahead of an EU environment council meeting on 5 March, a large group of countries, including France, Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Finland and Latvia, are expected to call for the Commission to set out a new EU 2030 target in June, so that an agreement between EU governments can be reached in time for the EU-China Summit.

The 55% target would not be sufficient to limit global heating to 2°C, let alone to 1.5°C. To avoid a full-blown climate crisis, environmental groups are calling on the EU to cut greenhouse gas emissions by at least 65% by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels) and to achieve net-zero emissions by 2040.

PAINFUL DELAY

The longer governments wait to reduce emissions, the steeper and tougher these cuts will need to be in future. A recent UN report calculated that “had serious climate action begun in 2010, the [global] cuts required per year to meet the projected emissions levels for 1.5°C would only have been 3.3% per year on average. However, since this did not happen the required cuts in [global] emissions are now 7.6% a year on average.” This means, at a bare minimum, that the EU must commit to yearly reductions of 7.6% a year between 2020 and 2030, reaching just over a 65% cut in emissions by 2030. Even steeper cuts will be needed if governments do not start drastically reducing emissions now.

Average world temperatures have already increased by over 1°C. From mega-hurricanes to monster fires, this has caused widespread devastation affecting millions of people. Europe too has started to feel the impact. The summer of 2019 saw major heatwaves in western Europe, with temperature records and drought in several EU countries, including Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, and Luxembourg. In recent months, Italy, Poland, the Czech Republic and the United Kingdom have been struck by unprecedented floods.

In 2018, a landmark UN climate science report illustrated in stark terms the major differences in the impact of 2°C of global heating, compared to 1.5°C. The report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that global emissions must be halved by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels), before falling to net zero as quickly as possible to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C. Developed economies like the EU have the ability and the responsibility to go further.

Contacts:

Sebastian Mang – Greenpeace EU climate policy adviser: +32 (0)479 601289, [email protected]

Greenpeace EU press desk: +32 (0)2 274 1911, [email protected]

For breaking news and comment on EU affairs: www.twitter.com/GreenpeaceEU

Greenpeace is an independent global campaigning organisation that acts to change attitudes and behaviour, to protect and conserve the environment and to promote peace. Greenpeace does not accept donations from governments, the EU, businesses or political parties.