The founding voyage

On the day when Greenpeace marks 50 years on the front lines of the fight to protect our environment, now is a time, more than ever, to look to the future.

Here and now billions must unite as a movement to take action around the world. To prevent the worst impacts of climate change and biodiversity collapse, to tackle the power structures and mindsets which enable environmental destruction, and to demand a green, peaceful, and just future.

Fifty years ago a crew of activists set out to sail into the path of a nuclear bomb blast and created Greenpeace.

Irving Stowe, co-founder of Greenpeace, described their plan to block the atomic bomb tests on the Aleutian island with a small ship as a “trip for life — and for peace”. None of the small group of 12 people knew that their trip would create a global organisation and change the world.

This year, on September 15, we will mark 50 years since that first voyage and remember the campaigns, the victories, the lessons we have learned, and the incredible people who have been the heart of Greenpeace.

We thank our campaigners who are delivering aid in the Amazon and the Pacific today, fighting fires in Russia, and storming parliaments and board rooms all over the world to speak truth to power. We thank the young girl who makes a small donation every month, the retiree marching alongside climate strikers, the campaigners and scientists shining a light on the seemingly all-powerful fossil fuel industries who hide behind lies to rob things that are priceless from generations yet to come.

The last 50 years have prepared us. Here and now we need to draw on all the lessons we have learned in the last 50 years and to be at our most creative, our most relentless, and our most united.

Here and now is the time that billions must push themselves to take action at the very edge of where they are comfortable, at the place where courage begins, and hope lights the way.

“It is amazing, what a few people sitting around their kitchen table can achieve”

Dorothy Stowe, Greenpeace founding member

Notable moments globally

1971: The founding voyage

The very first Greenpeace voyage took place on 15 September 1971 when Phyllis Cormack (also called “Greenpeace”) departed Vancouver, Canada for Amchitka Island.

The goal of the 12 people on board was to halt nuclear tests on the island by sailing into the restricted area. Irving Stowe, co-founder of Greenpeace, described the plan as a “trip for life —- and for peace”. None of the small group of 12 people knew that their trip would create a global organisation and change the world.

In fact, the ship and crew never reached the island – they were intercepted by the US coast guard and considered their journey a failure – until they returned home to discover hundreds of supporters waiting to greet them as they entered Vancouver harbour.

Despite not reaching their destination, the first ever Greenpeace action created so much pressure on the US government that the tests were cancelled, and Amchitka Island remains a nature reserve to this day.

1974: France ends nuclear tests

In 1974, France announced they would end their atmospheric nuclear testing program — a decision which effectively drove atmospheric testing out of the entire Pacific Ocean.

The tests had begun in the 1960s with a large amount of the effects on people and the environment completely ignored. In New Zealand, David McTaggart responded to an ad in the newspaper and volunteered the use of his boat, the Vega, to protest the testing.

After making preparations with Greenpeace in Canada, a five-man crew led by McTaggart set out from New Zealand in May on the yacht, renamed the “Greenpeace-III”.

The crew observed international law in establishing anchoring position, but ignored France’s unilateral declaration of the area as a forbidden zone.

The presence of the boat forced the French government to halt its test. A French Naval vessel eventually rammed the boat to end the embarrassing situation.

In August 1973, the Greenpeace-III again set sail for Moruroa Atoll to block the testing of nuclear weapons, this time accompanied by several other ships. The Greenpeace-III sails into the zone the French government has declared a prohibited area and is boarded by French navy commandos. Protesters David McTaggart and Neil Ingram are badly beaten and footage of the attack is smuggled off the ship by Ann-Marie Horne.

The incident caused worldwide outrage and, in 1974, France announced that it would end its atmospheric nuclear testing program.

1982: Whaling moratorium

After a 10-year campaign including countless confrontations at sea between Greenpeace activists and whalers, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) finally puts an end to commercial whaling.

When the campaign first began in the 1970s the total number of blue whales had decreased to an estimated less than 6000. Humpbacks showed a similar decline and populations of Pacific grey, sei, and sperm whales had been halved.

The images of Greenpeace activists confronting whaling fleets on the high seas and putting themselves in the way of the harpoons brought the issue to the attention of the wider public. Photographs of dead whales circulated the world and opinions began to turn against the whalers.

Campaigners around the world continued to rally public support against the practice and in 1979 the IWC established the Indian Ocean Whale Sanctuary as a practical conservation measure.

Greenpeace kept up the pressure until in 1982 the IWC finally delivered what the anti-whaling lobby had been fighting for: a moratorium on commercial whaling. After a decade of action, the world’s dwindling whale populations had a chance to recover.

1985: Greenpeace leads ‘Operation Exodus’ – the evacuation of Rongelap Islanders

The Rongelap island in the Pacific Ocean had suffered from the fallout from nearby US nuclear tests in 1954.

While the inhabitants of the Bikini and Enewetak islands were evacuated from their island homes prior to the nuclear tests, the inhabitants of Rongelap – some 150 kilometres away were not so fortunate.

Within four hours of the detonation of the 15 megaton “Bravo” bomb, fallout was settling on the island. Islanders reported a fine white ash landing on the heads and bare arms of people standing in the open. It dissolved into water supplies and drifted into houses.

In 1957, the US government deemed Rongelap safe for habitation. However, the rate of miscarriage among women who lived there would be more than twice that of women who had never been exposed to such high levels of radiation.

The islanders reached out to Greenpeace activists for help and on May 17 the Rainbow Warrior arrived in the area.

In the next 10 days Greenpeace crew evacuated more than 300 Islanders and over 100 tons of building materials to the safer island of Mejato 180 kilometres away.

1985: The bombing of the Rainbow Warrior by the French government

On 10 July 1985, the Greenpeace ship the Rainbow Warrior was moored in Auckland, New Zealand — ready to confront nuclear testing in the Moruroa Atoll — when French secret service agents planted two bombs on the hull.

The resulting explosion sank the ship and killed 35-year-old Portugal-born Greenpeace photographer Fernando Pereira.

Initially, the French government denied all knowledge of the operation, but it became soon obvious that they were involved. Eventually, French prime minister Laurent Fabius appeared on television and told a shocked public that the agents of the DGSE (Secret Service) sank the ship, and they acted on orders.

The world reacted with shock and anger to a foreign government choosing to respond to peaceful protest with deadly force.

Greenpeace replaced the original Rainbow Warrior with a new vessel, and for 22 years, the second Rainbow Warrior campaigned for a green and peaceful future. In 2011, the third Rainbow Warrior — the world’s first purpose-built environmental campaigning ship — was launched to carry on the original’s spirit.

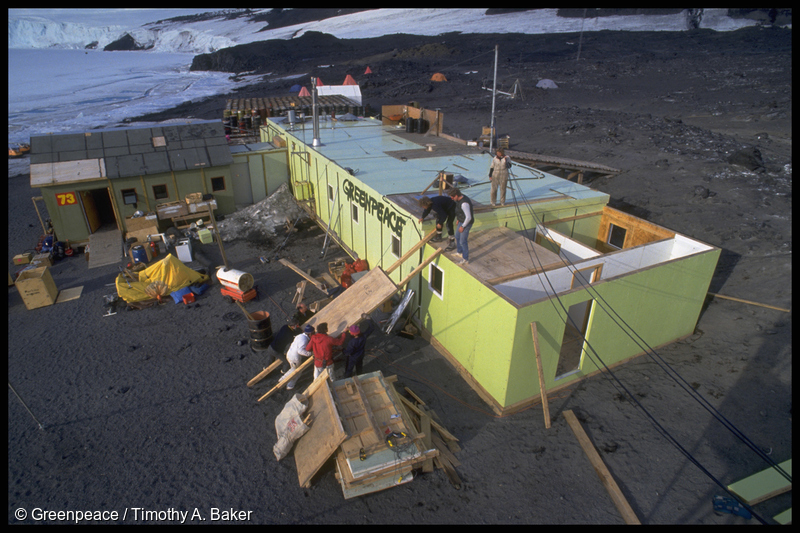

1991: World Park Base and the Antarctic

In 1987, Greenpeace established the World Park Base — a year-round Antarctic base located at Cape Evans on Ross Island in the Ross Dependency. The base was created in order to allow Greenpeace to have a seat at the bargaining table for the Antarctic Treaty Nations.

Greenpeace activists ran the base, in one of the world’s most isolated regions, from 1987 to 1991.

The team monitored pollution from neighbouring bases and held other nations accountable for their actions. In 1990, Greenpeace made headlines when 15 protesters blocked the French from building an airstrip at Dumont D’Urville. The construction work was controversial because it involved dynamiting habitats of nesting penguins. French scientists even admitted an airstrip violated terms of the Antarctic Treaty.

The base was finally closed in 1991 when the members of the Antarctic Treaty agreed to adopt a new Environmental Protocol, including a 50-year minimum prohibition on all mineral exploitation. By 1997, the protocol had been ratified by all TK nations with bases on Antarctica.

1993: London Dumping Convention cracks down on ocean waste

Following a 15-year campaign which involved numerous at-sea actions, submissions, and the rallying of public support by Greenpeace and allies, the London Dumping Convention bans ocean disposal of low-level radioactive wastes and the resolutions to end the dumping and incineration of industrial wastes.

The convention was an extremely powerful achievement in Greenpeace’s long-running — and continuing — campaign for healthy oceans.

1995: Brent Spar campaign leads to major victory in fight against dumping at sea

One of Greenpeace’s most widely-known actions, the occupation of the Brent Spar Oil Rig, took place in the North Sea in June 1995.

Activists occupied the rig for more than three weeks as part of a coordinated worldwide campaign putting pressure on Shell’s proposed “deep sea disposal” of the rig that included 11,000 kilos of oil into the ocean.

The campaign was eventually successful with Shell abandoning its plans to dispose of the oil rig in the ocean.

1995: The scream that was heard around the world

In June 1995, the French government announced it would persist with eight underground nuclear tests at Moruroa atoll before finally ratifying the UN’s comprehensive nuclear test ban treaty and ending their incredibly unpopular program.

Greenpeace replied by sending the Rainbow Warrior II to Moruroa to repeat its namesake’s 1973 mission – to protest and publicise the tests, and if possible to disrupt them.

The Rainbow Warrior and another Greenpeace vessel approached the edge of the French exclusion zone on September 1. French warship the Prairial ordered the vessels to turn back but were only greeted by “Message received, no comment”.

French commandos then stormed the ships with grappling hooks and tear gas, arresting everyone on board. Campaign spokeswoman Stephanie Mills had shut herself in the radio room and was being interviewed by media when the windows were smashed and tear-gas grenades thrown inside. The screaming and coughing from those inside the room could be heard.

Video of the raid, and the audio of screaming peaceful protesters, travelled around the world and provoked a wave of opposition to the testing and in January 1996 the French President announced a “definitive end” to the program.

1997: Greenpeace creates Greenfreeze

Greenpeace revolutionises the refrigerator market with the creation of “Greenfreeze” a domestic refrigerator free of ozone depleting and significant global warming chemicals.

Greenpeace went on to collect the UNEP Ozone Award for the development of Greenfreeze. In the award ceremony the United Nations said: “Greenpeace International played an important role in sensitising governments to the need to phase out ozone-depleting substances. Not content with this, it developed a refrigerator system that is completely free of ozone-depleting substances”.

The Greenfreeze system was made freely available for commercialisation and is now marketed by several large European manufacturers, and several major companies in China are also considering a shift to the use of hydrocarbon coolants. In this way Greenpeace has made a significant and constructive contribution to the protection of the ozone layer.

2010: Greenpeace pressures Nestlé to stop rainforest destruction

Multinational food and drink processing conglomerate Nestlé first agrees to stop purchasing palm-oil from sources which destroy Indonesian rainforests. The decision caps eight weeks of massive pressure from consumers via social media and non-violent direct action by Greenpeace activists as the company concedes to the demands of a global campaign against its Kit Kat brand.

2015: Exposing over 30 years of illegal fishing in West Africa

In May 2015, Greenpeace East Asia and Greenpeace Africa released a report exposing over 30 years of illegal fishing by Chinese companies in West Africa.

Campaigners aboard the Esperanza discovered incidents of illegal, unreported, unlicensed (IUU) fishing by Chinese fishing trawlers, operated by state-owned companies, on average every two days. Moreover, the China National Fisheries Corporation was falsifying the tonnage of most of their boats. Greenpeace called on the authorities in China and the report received widespread international attention and in June, our campaigners were invited to the Ministry of Agriculture to discuss the issue.

In July, the National Fishing Inspection Agency released new regulations requiring newly built distant fishing vessels to provide proof of adhering to international tonnage standards.

2019: Big polluters found responsible for human rights harm

In December 2019, the Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines (CHR) presented their initial report on the resolution for the National Inquiry on Climate Change (NICC) in Madrid during COP25.

The results of the nearly three-year investigation found that, for the first time ever, that the world’s carbon majors were responsible for human rights harms resulting from the climate crisis.

It was the world’s first national human rights investigation into big polluters and was a landmark climate justice victory for impacted communities and reflected many years of work. Greenpeace Southeast Asia, together with 14 organisations and 20 individuals, filed the petition on 22 September 2015 calling for this investigation to take place. Over 100,000 signatures were gathered in support of the initiative online from Change.org, SumOfUs and Greenpeace Southeast Asia, while eight international NGOs also provided advice and support.

2021: Groundbreaking court decision in climate case against Shell

In a historic verdict, a Dutch court rules that Shell must reduce its CO2 emission by net 45% in 2030 relative to 2019. This is the first time a major fossil fuel company was held accountable for its contribution to climate change and ordered to reduce its carbon emissions throughout its whole supply chain.

The climate case was brought by Friends of the Earth Netherlands (Milieudefensie), along with Greenpeace Netherlands, other NGOs, and 17,379 individual co-plaintiffs.

The ruling is a clear message to the fossil fuel industry. Legal experts expect that the ruling will spark more climate litigation around the world. Different jurisdictions mean different legal avenues, but plaintiffs around the world can and will use the underlying principle that fossil fuel producers have obligations to reduce emissions in line with the science.