From the Philippines to Thailand, Kalmaegi shows how the world left Global South countries exposed again

Each time a storm tears through Southeast Asia, familiar scripts quickly follow. We are told we weren’t prepared enough. We are lectured about poverty and resilience, as though these conditions appeared naturally and not through decades of global inequality. The story the world tells about developing countries is one of perpetual helplessness, an easy narrative that masks a far harder truth.

The truth is much harder to swallow. We are in this position because wealthy nations and fossil fuel companies built an economy that forces developing countries, including here in Southeast Asia, to carry the heaviest burdens of a crisis we contributed least to. Germanwatch’s Climate Risk Index tells the same story. Three Southeast Asian countries, namely the Philippines, Myanmar, and Vietnam, rank among the world’s most affected by extreme weather.

Typhoon Kalmaegi (known in the Philippines as Typhoon Tino) is the latest proof. It swept across the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, leaving destruction that communities will be grappling with for months. Days later, Super Typhoon Fung-wong (Uwan) arrived with even stronger winds and heavier rains. New rapid attribution studies generated using the Imperial College Storm Model (IRIS) model reveal that climate change—driven overwhelmingly by the burning of fossil fuels like coal, oil, and gas—intensified both storms and left more economic damages. Fung-wong’s wind speed increased by 5.5% in the Philippines and rainfall by 10.5%, while Kalmaegi’s wind speed rose by 3% and rainfall by 8.6% as it hit Vietnam.

In the Philippines, Kalmaegi claimed 269 lives and left more than $9 million in agricultural losses and over $8 million in damaged infrastructure. Vietnam recorded about $300 million in economic losses, with close to 60,000 homes damaged and over 39,000 hectares of crops destroyed. In Thailand, Kalmaegi compounded weeks of flooding in Ayutthaya, a province in the vulnerable Chao Phraya Basin, inundating over 63,000 households and damaging homes, cultural heritage, and infrastructure. The World Bank notes that Thailand is among the world’s most flood-exposed nations, with climate change projected to intensify river flooding and escalate future losses.

Yet the region is often portrayed as chronically vulnerable instead of chronically wronged. While contributing only a tiny fraction of global emissions, they repeatedly face cyclone seasons that are now wetter and more unpredictable. Meanwhile, the nations and corporations that built their wealth on fossil fuels continue to profit while denying responsibility for the damages their emissions have created, all while investing heavily in Southeast Asia to expand fossil fuel projects that lock communities into decades more dependence on coal, oil, and gas.

As COP30 moves deeper into negotiations, progress remains slow and the ambition gap continues to widen. Fossil fuel lobbyists now outnumber several country delegations, and new UN assessments warn that the world is far off-track from keeping 1.5°C within reach. World leaders must agree to a clear, time-bound roadmap for a full, just, and equitable fossil fuel phase-out. They must accelerate renewable energy transitions, enabling communities to access clean, affordable power. They must ensure that the shift away from fossil fuels like oil, coal, and gas protects workers and supports communities who have lived for decades in the shadow of fossil-fueled development.

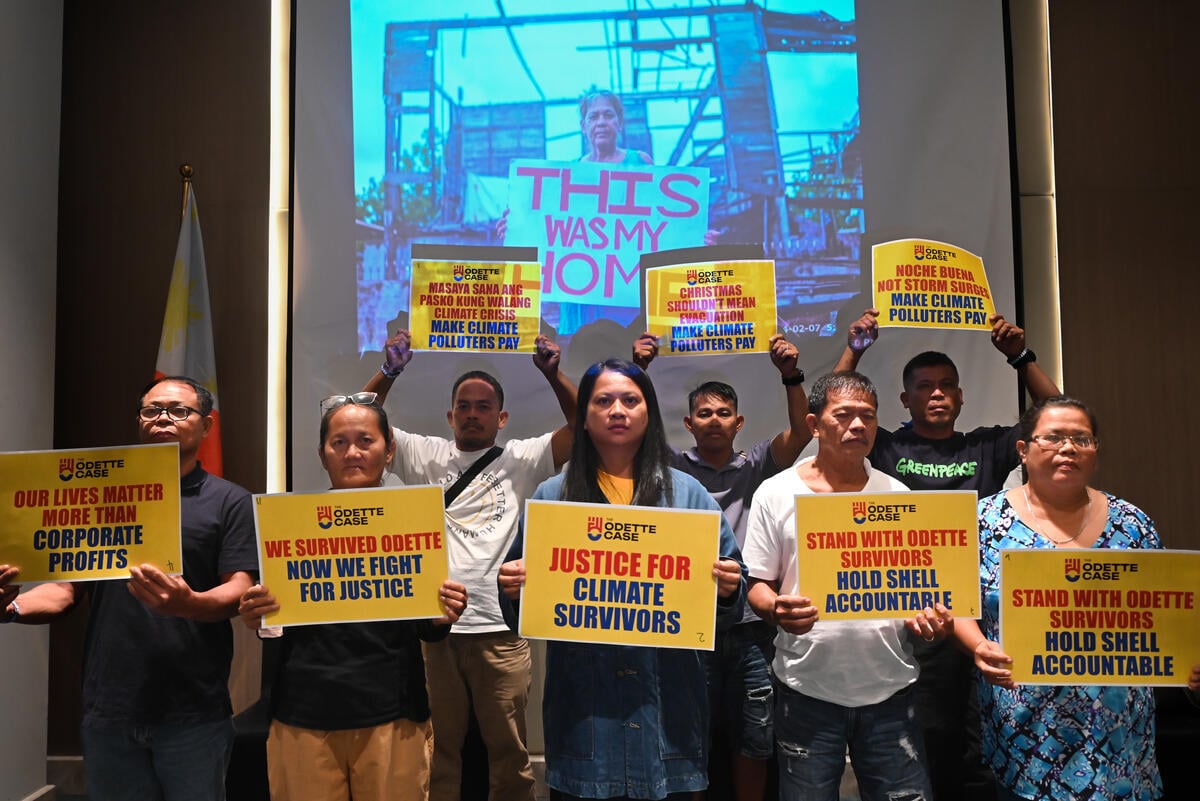

Above all, COP30 must deliver the finance that frontline communities need. Wealthy and historically high-emitting countries should provide new, public, and additional climate finance. The Loss and Damage Fund must finally function at scale. Recovery cannot be funded by loans that trap vulnerable nations in deeper debt. The Polluter Pays Principle must guide climate finance, and major fossil fuel companies must be held financially accountable for the harms they’re causing to the people and the planet.

Kalmaegi is a signal of a region being pushed beyond its limits. If COP30 fails to confront the root causes of these storms, Southeast Asia and other developing countries will continue to suffer the consequences of decisions made in boardrooms and capitals far from the damage.

The world owes developing countries more than sympathy. It owes justice and action that matches the scale of the crisis.

Jefferson Chua and Attapol Puangsakul are Greenpeace Southeast Asia’s campaigners in the Philippines and Thailand, respectively, working on key areas of climate litigation, policy, finance, and just transition.