Two of the Greenpeace founders, Irving and Dorothy Stowe, grew up during world wars, the dawn of a global peace movement, and a non-violent direct action movement inspired by Mahatma Gandhi.

In 1915, Irving Strasmich was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in a Talmudic Jewish family that emphasized worldly education. In 1936, he graduated from Brown University in economics, and entered Yale law school. He believed in Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, hope for working class people within the structure of American capitalism. Out of law school, he helped draft antitrust legislation, earned his pilot’s license, and joined the US World War II effort, where he was sent to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), President Roosevelt’s precursor to the CIA. Irving believed the US could help establish democratic freedom around the world. However, he was so upset by the Hiroshima bomb that he broke down in tears in front of the White House, returned home, and served as a lawyer for the Rhode Island Tax Commission.

Dorothy Rabinowitz, was born in Providence in 1920. Her mother, a Hebrew teacher, and her father, a jeweler, had immigrated to the US from Galicia, a once-independent region of central Europe torn by fighting during World War I. As a young woman, Dorothy met distinguished Jewish political activists in her home, including the future first president of Israel, Chaim Weizmann. She graduated from Pembroke College in English literature, became a purchasing officer for the US Navy during World War II, joined the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, and became president of Rhode Island’s first state employees union. When she won a 33% wage increase for social workers, Democratic governor John Pastore called her “a communist.”

Irving and Dorothy met in 1951, on a blind date at Brown University. Irving played the violin, and frequented Providence’s Celebrity Club, where he made recordings of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington. The Black jazz musicians had invited the Jewish lawyer into the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the NAACP. The couple married in 1953, with a Rabbi presiding and with renowned British jazz pianist George Shearing as best man. They spent their wedding night at a benefit banquet for the NAACP.

Dorothy and Irving joined the Quaker Society of Friends, became committed pacifists, and protested nuclear weapons. They adopted the Quaker idea of “bearing witness,” to injustice and speaking out to others. Irving offered pro bono legal services to citizens called before Senator Joseph McCarthy’s US House Un-American Activities Committee. He argued convincingly that pacifism was not unpatriotic. An avid letter writer and early riser, he could send off letters to President Eisenhower, to Secretary of Defense Charles Wilson, and to the editors of The New York Times all before breakfast.

Strontium-90

In 1955, Irving and Dorothy Strasmich had a son, Robert, and the following year a daughter, Barbara. From the example of Gandhi, they believed that citizens acting with integrity and courage could defeat powerful forces. From the Quaker tradition, Irving adopted the idea of “Replacing the Death culture with a Life culture,” a rally cry he would champion for the rest of his life.

After the horrors of World War II, the global peace movement gained momentum. In London, Bertrand Russell formed the Union of International Scientists opposed to nuclear bomb tests. On his deathbed, Albert Einstein drafted a disarmament declaration signed by fifty-two Nobel laureates.

Meanwhile, Harvard biologist Dr. Barry Commoner collected deciduous teeth from children in St. Louis and discovered the presence of strontium-90, a radioactive by-product of nuclear explosions. Strontium-90 in children’s teeth was the sort of horrifying image that people could understand, and a threat to which they would respond. The world’s militaries had become the world’s worst polluters. The peace movement, the civil rights movement, and the ecology movement began to merge.

When US federal law made civil defense drills compulsory, Irving and Dorothy joined the War Resisters League by refusing to take shelter. Irving declared that hiding from nuclear attack was a fraud, the arms race was a waste of resources, and radiation from weapons testing was killing people. Irving and Dorothy emphasized that the disarmament movement integrated class, religions, and cultures, and that business leaders and union leaders stood side by side at peace marches.

In the spring of 1960, protesters from A.J. Muste’s Campaign for Nonviolent Action marched from Boston to Groton, Connecticut, to protest US submarines designed to carry nuclear missiles. When the marchers passed through Providence, Irving and Dorothy hosted them and continued with the march to the boat yard. A small group paddled boats in front of launching submarines, boarded them, were arrested, and received 19-month jail sentences.

In 1961, when President Kennedy began sending US Marines to Vietnam, Irving and Dorothy decided to leave the US in protest against paying taxes for war and weapons testing. They moved to New Zealand, where Irving joined the University of Auckland law faculty and Dorothy got a position as a social worker.

In New Zealand, they adopted the name “Stowe,” after nineteenth century American abolitionist, feminist, and author, Harriet Beecher Stowe, who praised Quaker pacifists in her books. They led peace marches to the US consulate and attended Quaker meetings. However, in 1965, under pressure from the US, New Zealand began sending troops to Vietnam, the Stowes felt outraged, and once again looked for a new home.

In April 1966, Irving stopped in Vancouver, Canada on his way back from Rhode Island. The city was bathed in sun, fruit trees were in bloom, and the blue water and snow-capped mountains soothed his heart. Canada was not sending troops to Vietnam and was quietly accepting American pacifists evading the military draft. Irving and Dorothy decided to move their family — Bobby now 11, and Barbara 10 — to Canada.

They purchased a two-story, wooden home in the quiet neighborhood of Point Grey, near the University of British Columbia. The Stowes were not naive; they knew that Canadian companies mined uranium for American weapons and that some 40 Canadian universities provided military research to the war effort. Irving discovered that Canadian contractors in Suffield, Alberta devised chemical and biological weapons for the US, including napalm and Agent Orange used in Vietnam. There was nowhere to run. They decided to remain in Canada and work for peace.

Irving, now 51 years old, told Dorothy that the time had come for him to be a full-time activist. Dorothy found a job in family services, and Irving registered as a private estate planner, but he would dedicate the rest of his life to stopping the bomb and bringing about peace. Their quiet home in Vancouver would soon become a hub of global significance.

Make it a green peace

Two journalists in Vancouver caught Irving’s attention. Bob Hunter wrote a column in the Vancouver Sun that addressed progressive issues including peace, civil rights, women’s rights, and ecology. Ben Metcalfe hosted a CBC naturalist show, “Klahanie,” featuring local ecology stories. Irving began writing to both journalists, promoting peace movement events. They met Quaker pacifists Jim and Marie Bohlen at an anti-war demonstration and became close friends.

The Stowes supported virtually every disarmament or ecological campaign in Vancouver. They belonged to the Quaker Friends Service Committee, the World Peace Council, and the BC Environmental Coalition (BCEC). With the Society to Advance Vancouver Environment (SAVE), they promoted a pedestrian mall for the city core, and with the Stop Pollution from Oil Spills (SPOILS) they protested oil tanker traffic in the Georgia Straight. Dorothy kept track of the correspondence and replied to every offer of support. She not only earned their family income, she also acted as secretary for several groups. Her file cabinet was a sea of acronyms.

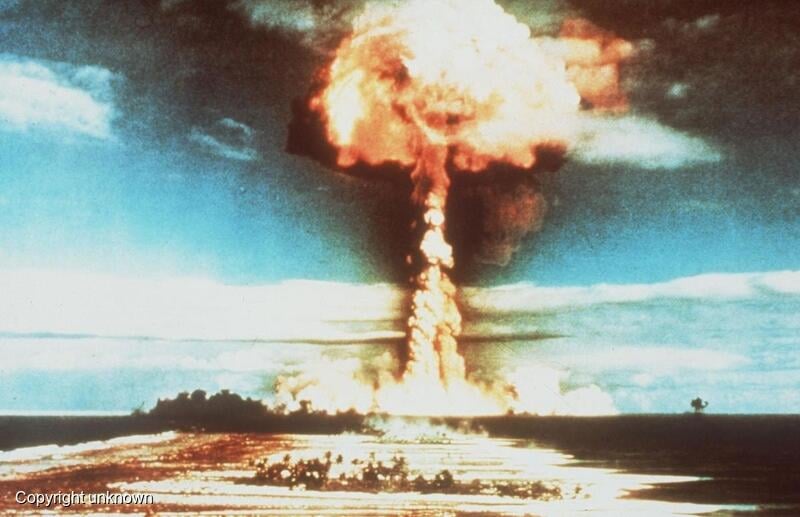

Then, in August 1969 the US announced a 1-megaton nuclear bomb test, “Milrow,” scheduled for October on Amchitka Island, 4,000 kilometers northwest of Vancouver in the Aleutian archipelago. Irving and Dorothy led peace marches to the US embassy, where they met Deeno Birmingham from the BC Voice of Women and Lille d’Easum, who wrote about nuclear radiation. Bob Hunter wrote a column about the threat of a tsunami caused by the detonation. For a demonstration at the US border, Hunter made a sign that read: “Don’t Make a Wave: Stop the Bomb.” The Stowes met Hunter at the demonstration, felt inspired to start an organization dedicated to stopping the US bomb tests.

However, the next morning, the US detonated the Milrow bomb test some 1,300 meters underground. The island surface heaved five meters into the air. Fish were blown from lakes, house-size chunks of granite fell into the sea, and nesting birds and sea otter carcasses floated in the shoreline foam. The University of Victoria recorded a 6.9 Richter scale shockwave. When the US announced a follow-up test, five-times as powerful, for the fall of 1971, the Stowes, Bob and Zoe Hunter, Ben and Dorothy Metcalfe, Birmingham, d’Easum, the Bohlens, and other peace activists met at the Stowe home to plan strategy to stop the blast. Borrowing Hunter’s slogan, they called the new organization “The Don’t Make A Wave Committee.”

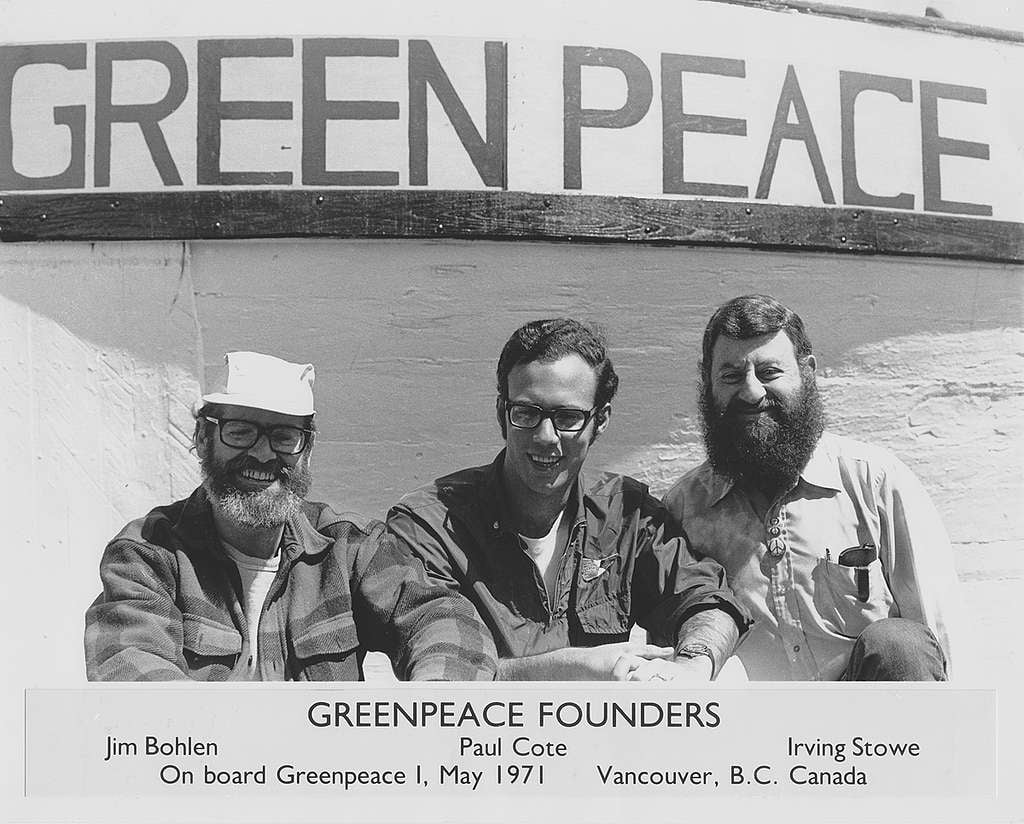

As attendance grew, they moved meetings to the Unitarian Church. Marie Bohlen, borrowing a Quaker tactic, suggested, “We should just sail a boat into the test zone.” The idea appealed to everyone, and they decided to find a boat. At the end of the meeting, Irving in his typical manner, flashed the “V” sign and said “peace.” Twenty-two year-old Bill Darnell who had organized an “Ecology Caravan” in the region, responded: “Make it a Green Peace!”

Darnell’s spontaneous slogan perfectly articulated the merging peace and ecology movements. Group members began to call the campaign “Green Peace,” and Marie Bohlen’s son, Paul, designed a button with green lettering on a yellow background, with the ecology symbol, the peace symbol, and in the middle, the single word: “Greenpeace.”

Amchitka

Stowe reckoned they would need about $45,000 for a boat charter, fuel, and provisions for the voyage. Twenty-five-cent buttons weren’t going to do it, so Stowe decided to organize a benefit music concert. He wrote to Joan Baez, whom he had met eight years earlier through the Committee for Nonviolent Action. Baez could not perform, but she donated $1,000, recommended Joni Mitchell and Phil Ochs and gave Stowe their phone numbers. When both agreed to perform, Irving set a date for October 16, 1970.

Joni Mitchell invited rising star James Taylor, Canadian band Chilliwack joined the show, and the concert was a sellout. Phil Ochs, the senior pacifist artist at 31, opened the show and spoke directly to the raison d’etre of the evening with his “I Ain’t Marchin’ Anymore.” Chilliwack got the crowd in a good rock and roll frenzy. James Taylor stunned the crowd with the cryptic “Carolina In My Mind,” and “Fire And Rain.” Joni Mitchell’s “Chelsea Morning” and “Big Yellow Taxi,” brought shrieks of joy from the crowd. Irving Stowe, grinning and raising the peace sign, delivered flowers to Mitchell.

After all expenses were paid, the event netted over $17,000. By the end of October, the Don’t Make A Wave Committee had $23,467.02 in the bank, all accounts kept impeccably by Irving and Dorothy Stowe.

Crossing the Gulf of Alaska during the autumn storm season was dangerous. Some mariners told them they were crazy. Nevertheless, on the waterfront south of Vancouver, Jim Bohlen met fisherman John Cormack, who agreed to take them to Amchitka Island on his 63-foot fishing boat.

Irving Stowe was vulnerable to severe sea sickness, so he could not go. Marie Bohlen had planned to join the crew, but a few days before departure, she decided it was too risky for both her and her husband Jim to leave their children, so she stepped down. At dusk on September 15, 1971, the Phyllis Cormack, rechristened “Greenpeace” for the voyage departed Vancouver. Irving, Dorothy, Marie worked with other volunteers from Vancouver. Dorothy Metcalfe, a seasoned journalist, operated a marine radio link to the boat, released stories to the media, and pressured Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to put pressure on the US government.

The voyage created massive public attention. Robert and Barbara Stowe helped organize Vancouver students to walk out of schools in protest. Irving and Dorothy achieved their vision of walking with business leaders and union leaders in a protest march. Time magazine reported: “Seldom, if ever, had so many Canadians felt so deep a sense of resentment over a single US action.” Thirty U.S. senators urged the Nixon government to halt the test.

On the way up the coast, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Indigenous community at Alert Bay, BC, invited the crew to a ceremony and blessed the voyage. When they reached the Aleutian Islands, the US Coast Guard seized the vessel and sent it back to Sand Spit, Alaska to go through customs, delaying the trip. On November 6, 1971, before the boat could reach Amchitka, the US detonated the 5.2-megaton bomb. The blast created a molten cavern inside the rock, fissured the volcanic substrate, and blew a mile-wide crater in the island surface.

At first, the crew felt that they had failed, but when they returned to Vancouver, they were treated as heroes. The voyage s쳮ded in capturing the imagination of activists around the world. Opposition to the Amchitka tests became so intense that President Nixon cancelled the program on the island a year later. Eventually, Amchitka became a bird sanctuary, and one of the most influential environmental groups of the twentieth century had established its original and highly visible protest tactic.

In May 1972, the group officially changed its name to The Greenpeace Foundation. Hunter, Darnell, and others envisioned future ecology actions, which led to the 1975 whale campaign and eventually to a global Greenpeace organization.

On October 28, 1974, Irving Stowe passed away from pancreatic cancer at the age of fifty-nine. His passing gave the group pause and reminded people: this mission is serious. “No one could say that Irving wasted his time here,” Bob Hunter wrote in his Vancouver Sun column. “When others were waiting to see what nightmare would materialize next, Irving was moving like a human whirlwind toward the goal of heading the nightmare off.”

Dorothy Stowe continued to support peace and social justice for decades and got to witness the evolution of Greenpeace around the world. In 2005, when Irish rock band U2 played Vancouver, singer Bono invited Dorothy to the show and dedicated the song “Original of the Species” to her. On July 23, 2010, Dorothy, at the age of 89, passed away peacefully at UBC Hospital in Vancouver.

Irving and Dorothy Stowe were natural leaders, who, by their own example, inspired commitment in others and thus launched one of the world’s most effective environmental and peace organizations.