Seabed mining in Aotearoa

Seabed mining and deep sea mining are the destructive practices of stripping the ocean’s seabed for metals and minerals.

Here’s what you need to know about seabed mining and how you can help stop this industry from getting started in Aotearoa and the Pacific.

Seabed mining in Aotearoa and deep sea mining in the Pacific

Seabed mining mainly refers to mining the relatively shallow waters around the coastline of Aotearoa. Australian-owned companies like Trans-Tasman Resources are proposing to mine the seabed off the Taranaki Coast at depths of up to 50 metres. Deep sea mining refers to the proposed practice of mining the seabed of the Pacific Ocean or the Arctic at depths of up to 5,500 metres.

Among many other risks to people and nature, mining the ocean floor in this way could damage the oceans beyond repair, threatening their ability to help fight climate change and sustain life on planet Earth.

Greenpeace is campaigning to stop all ocean floor mining, but in Aotearoa, the threat of seabed mining in Taranaki is imminent.

Any political party that takes environmental protection seriously must stand against Trans-Tasman Resources’ plan to seabed mine in the South Taranaki Bight.

Sign the petitionWhy do miners want to target the seabed?

Seabed mining and deep sea mining generally involves removing metals and minerals from the sea floor. Deep below the Pacific ocean’s surface, deposits of metals and minerals like manganese, nickel and cobalt have built up on the seafloor into potato-sized ‘polymetallic nodules’ over millions of years.

Mining companies want to extract these metals by using gigantic machines capable of operating at up to a depth of four thousand metres.

Why is seabed mining bad?

Seabed mining would be extremely destructive, destroying beautiful habitats and ecosystems that aren’t yet fully understood.

Seabed mining would cause massive damage to the ecosystems which sustain life all the way up the food chain, that all of us rely on.

Tangata Whenua and Pacific Island communities, particularly those living subsistence lifestyles in coastal areas, will pay the highest price. At the centre of their identities and ways of life, Tangata Whenua and Pacific Peoples have deep spiritual and cultural ties to the ocean.

Things you can do to stop seabed mining

Together, we can stop seabed mining before it starts. Use your voice, join us today.

-

PETITION: Stop deep sea mining

It’s time for New Zealand to take a stand. Join our call on the New Zealand government to back a global moratorium on seabed mining.

-

Send a protest email to the seabed mining companies

Trans-Tasman Resources (TTR) has a plan to rip up 50 million tonnes of the South Taranaki seabed every year for over 35 years. This would be the world’s first commercial seabed mine.

-

Call on Chris Hipkins to take a stand against seabed mining

Any political party that takes environmental protection seriously must stand against Trans-Tasman Resources’ plan to seabed mine in the South Taranaki Bight.

Seabed mining a fast track to deep sea mining in Aotearoa

Seabed mining in Aotearoa could be a fast track to deep sea mining in the Pacific.

One of the first projects that could go ahead under the Luxon Government’s controversial Fast Track Approvals Bill is seabed mining off the coast of Taranaki. The Australian-owned company Trans-Tasman Resources is planning to suck up 50 million tons of iron sand every year for 35 years to extract vanadium, iron and titanium. Experts say it will have a devastating impact on rare marine life.

Under the Fast Track legislation, Trans-Tasman Resources could win approval to mine, despite losing many legal hearings and more than 10 years of fierce opposition from the local iwi and hapū, environmentalists and the community. If they are given permission to mine the seabed, that could open the floodgates to deep sea mining across the Pacific and around the world.

Add your name to the open letter to companies considering using the Fast Track to dodge laws designed to protect people and nature.

-

Threatened whale species in the Pacific found in areas targeted by The Metals Company for deep sea mining, scientists warn

A scientific survey of two areas targeted by The Metals Company for deep sea mining in the Pacific Ocean has confirmed the presence of whales and dolphins, including sperm whales,…

-

This is how you’ve made a difference with Greenpeace so far in 2025

In this issue of our magazine Kākāriki, you can read how you are how you are protecting our oceans, climate, forests, and communities here in Aotearoa and around the globe.

-

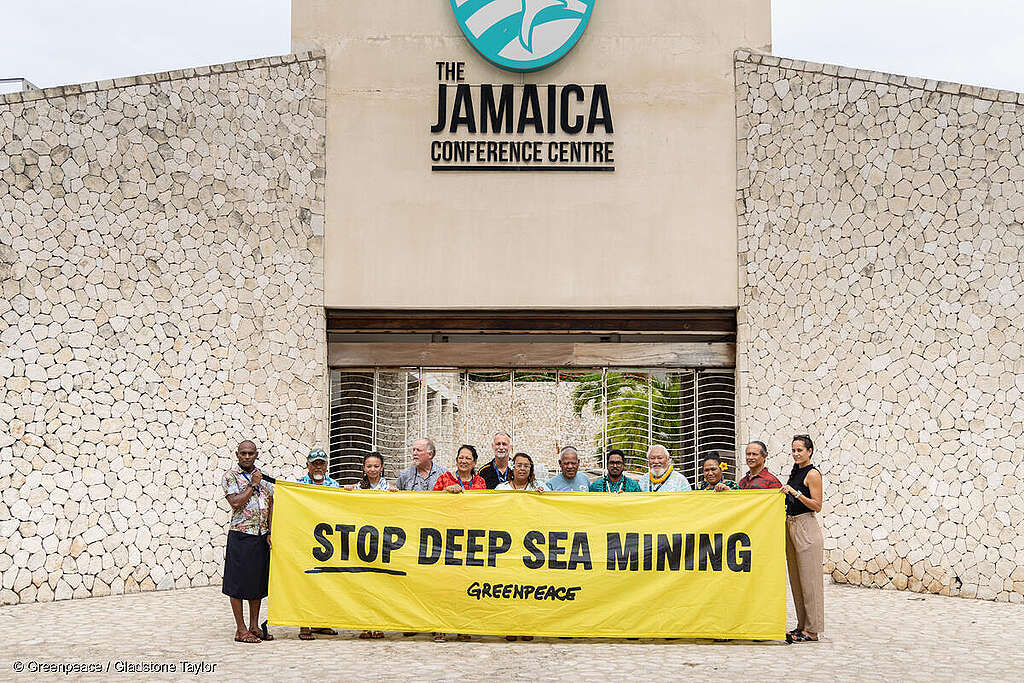

Greenpeace protest deep sea mining at UN Ocean Conference

Nice, France, 11 June 2025 – Greenpeace France activists today deployed a large banner reading “three million people stand against deep sea mining” outside the UN Ocean Conference (UNOC) in…

Seabed mining FAQs

We answer your questions about seabed mining:

Vulnerable coastal communities, especially in the Pacific, will pay the highest price. Peer-reviewed science shows that deep sea mining is almost certain to cause lasting damage to deep sea ecosystems. This means potentially severe impacts on countries and communities that depend on the Pacific Ocean.

Deep sea mining could harm the fish populations that provide food and livelihoods for many Indigenous Pacific communities. These communities have profound cultural and spiritual ties with the sea.

International opposition to the deep sea mining industry continues to grow.

A growing list of countries – including New Zealand and several Pacific Island nations, Germany, France, Spain and Chile – are proposing a pause or a ban on issuing licences. Five more countries joined the call at the last International Seabed Authority meeting in July-August 2024, bringing the total to 32 nations.

Seabed mining is a very new industry. Apart from a few small tests, no commercial mining has happened yet. But the companies involved are preparing to start full-scale production.

Seabed mining is the practice of removing metals and minerals from the ocean’s seabed. Thousands of metres below the surface, deposits of these metals and minerals like manganese, nickel and cobalt have built up on the seafloor into potato-sized nodules over millions of years.

To mine these metals, gigantic machines weighing more than a blue whale would scoop deposits from the deep ocean floor. They’d then pump the mined material up to a ship through up to several kilometres of tubing. Sand, seawater and other mineral waste would then be pumped back into the water.

Like mining on land, deep sea mining is extremely destructive. But mining the ocean floor is risky for so many reasons.

The full environmental impacts of deep seabed mining are hard to predict. But they’re likely to be highly damaging, both within and beyond the areas being mined.

The oceans are facing more pressures now than at any time in human history, and are threatened by overfishing and the climate crisis. Our oceans absorb and store carbon, and give more than three billion people their livelihoods.

Danger to habitats

The nodules containing the metal deposits have taken millions of years to form and are one of the keystones of deep sea life. When they are gone, they cannot be replaced; nor can the ecosystems that thrive around them. This would cause disruption all the way up the food chain that Pacific communities – and all of us – rely on.

Mining these deposits would destroy biodiversity and habitats which have far reaching benefits to all life on Earth that aren’t fully understood. The deep ocean is a vast reservoir of biodiversity, from glowing sharks to armoured snails, with new species being discovered every year.

Find out more about seabed mining in Aotearoa and around the world:

-

What is seabed mining, and how does it threaten the ocean?

Seabed mining is a destructive mining practice that involves dredging up the seabed for precious metals. It’s an immediate threat in Aotearoa.

-

Dark oxygen discovered in the deep sea spells trouble for seabed mining industry

Scientists have found a source of ‘dark oxygen’ 4,000 meters below the surface of the Pacific in the target zone for deep sea mining. The discovery could have far-reaching implications for science and the wannabe deep sea mining industry.

-

Deep sea mining and neocolonialism in the Pacific

The recent milestone of the Global Oceans Treaty, which aims to protect marine biodiversity and regulate human activities in the high seas, was a hard-won victory for the international community.…

-

5 reasons to be hopeful in the fight against deep sea mining

In just a few days, another crucial International Seabed Authority (ISA) meeting will start. From July 15th to August 2nd, world leaders will discuss the future of the deep ocean.

-

Deep sea mining scars remain fifty years on

What do you see in this photo? Can you discern the deliberate pattern formed by the grey-blue dots? Can you feel the stillness in this place?

-

Deep Sea Mining: a threat to the Pacific Ocean despite recent Global Oceans Treaty win

The vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean is home to an incredible array of marine life and resources that are vital for our planet. However, a dangerous threat looms beneath…

-

World Oceans Day – Why protecting the oceans means protecting people

The phrase ‘ocean protection’ will usually conjure up images of how human activities and our rapidly changing climate are impacting marine life. From fishing vessels with nets the size of…

-

What global deep sea mining negotiations are missing

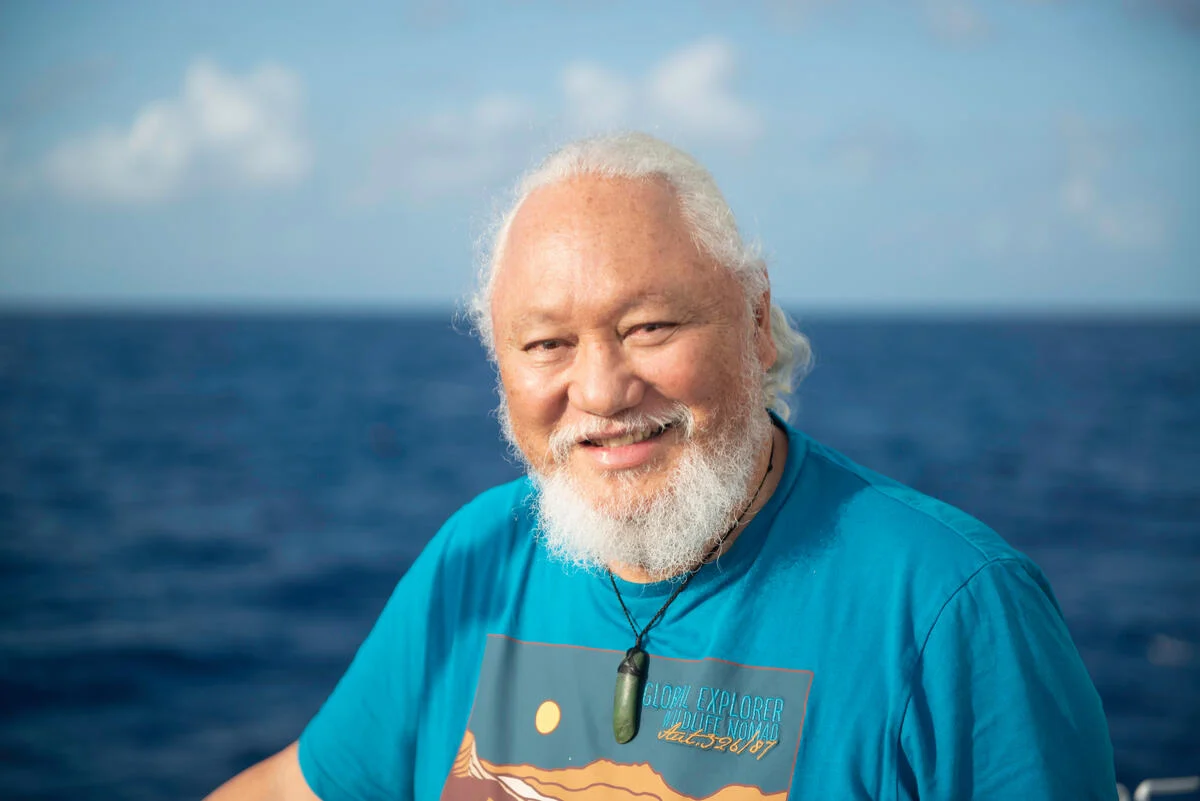

Solomon Pili Kahoʻohalahala, known as Uncle Sol, is a member of the Greenpeace International delegation at the International Seabed Authority (ISA) meeting in Jamaica, where governments are gathering to decide…

-

New research reveals huge carbon store in the seabed

Protecting and effectively managing oceans and seabeds are crucial in the fight against climate change. Oceans store vast amounts of carbon, locking it away from the atmosphere for hundreds to even thousands of years.

-

What if whales took us to court? A move to grant them legal personhood would include the right to sue

In a groundbreaking declaration earlier this month, Indigenous leaders of New Zealand and the Cook Islands signed a treaty, He Whakaputanga Moana, to recognise whales as legal persons.

Support our work

Companies and governments want to start deep sea mining. But we will be out there resisting them, every step of the way. Support our work through a regular donation or a one-off gift.