For fifty years Greenpeace has been making history by confronting and stopping environmental destruction. It has also investigated and documented environmental crimes and pollution, and organised scientific studies, legal cases, and mass mobilisations.

Over those five decades, Greenpeace has evolved from a single crew of eco-warriors in a creaky wooden boat into the world’s most successful campaigning environmental NGO (Non-Governmental Organisation) with dozens of offices around the planet and a small fleet of ocean-going boats. This includes a long history and deep cultural roots here in Aotearoa.

The NZ Government recently announced a new history curriculum, which for the first time will include teaching the late 20th century history of Aotearoa and its role in the wider Pacific region, and the evolution of a national identity with cultural plurality. This new curriculum is to be taught in all schools and kura from 2023.

The recent publication of a new history of Greenpeace in Aotearoa by the Greenpeace Educational Trust is a timely free-to-view online resource for teachers and educators which is relevant to the history of the peace and environment movements, and the bombing of Greenpeace’s flagship Rainbow Warrior on the 10th July 1985. It can help students study and understand different perspectives of history and interpret the recent past.

It also aims to help students better understand the role of environmental NGOs – in this case, Greenpeace Aotearoa – and its main achievements over the past 50 years from helping to end nuclear weapons testing and protecting Antarctica from oil and minerals exploitation, to helping to end new offshore oil and gas exploration in Aotearoa and cutting carbon emissions from the energy sector.

It can also help social studies students to understand, “how societies work and how people can participate in their communities as informed, critical, active, and responsible citizens”.

Origins in Aotearoa

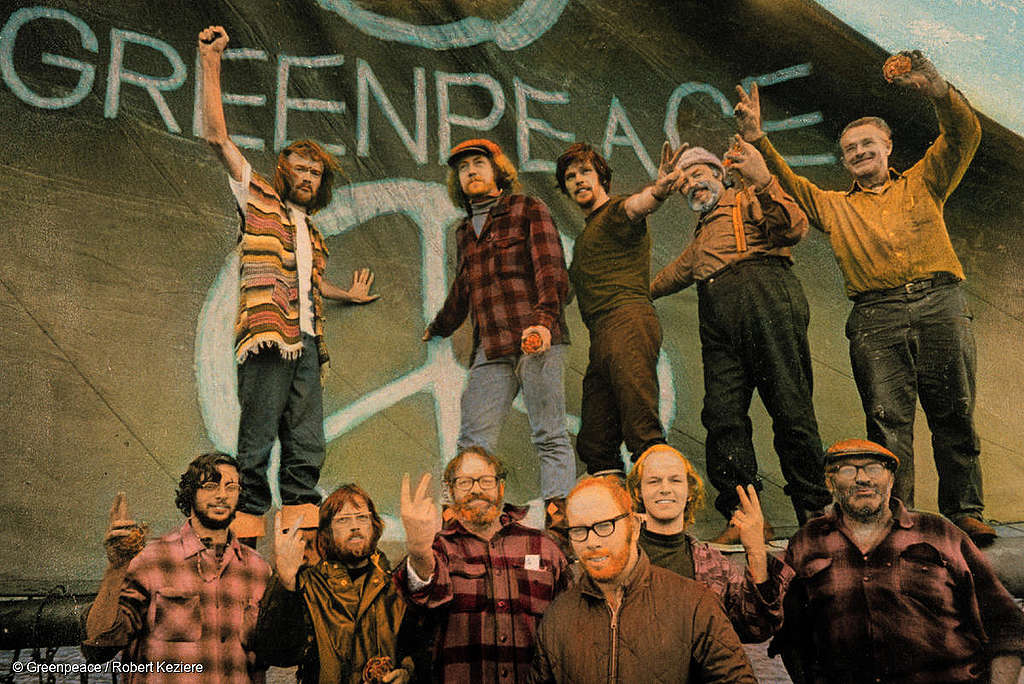

Greenpeace Aotearoa was one of the first Greenpeace organisations to be set up after the original Greenpeace Foundation in Canada in 1971. It brought together a network of young anti-war and anti-nuclear activists around Aotearoa who supported the first Greenpeace protest voyage from Aotearoa to the French Government’s nuclear weapons test site at Moruroa Atoll in 1972. David McTaggart, Anna Horne and others set sail from Auckland for Moruroa aboard SV Vega (renamed Greenpeace III) 50 years ago in April 1972. Then in July 1972, three more small boats set sail from Aotearoa – Boy Roel, Tamure, and Magic Isle – to join SV Vega.

The following year a new and larger flotilla sailed from Aotearoa to Moruroa comprising SV Vega, Fri, Spirit of Peace, Bluenose, Barbary, Arakiwa, and Tanea. Fri skipper David Moodie, navigator Martini Gotje, crew member Naomi Petersen and others helped to formalise the founding of an organisation through the establishment of Greenpeace Aotearoa as an incorporated society in 1974.

As public pressure mounted to end the nuclear tests, the French Government announced it would halt its atmospheric nuclear tests in 1975, and move them into ‘underground’ shafts drilled down under Moruroa’s lagoon. Spurred on by this partial success, Greenpeace’s campaign continued and new campaigns were launched to halt commercial whaling, help ban nuclear ship visits, and to help stop the introduction of nuclear power stations into Aotearoa – each of which was successful.

More new campaigns followed in the 1980s and 1990s to protect Antarctica, end ‘wall-of-death’ driftnet fishing, ban ozone-depleting chemicals and stop toxic pollution. A global ban on ozone-depleting chemicals was agreed in 1987 that was passed into NZ law in 1996, an agreement to protect Antarctica was signed in 1991 and ratified in NZ law in 1998, and driftnet fishing was banned globally on the high seas in 1992 after a UN vote that Greenpeace Aotearoa helped make happen, and a global treaty on eliminating persistent toxic pollutants was agreed in Stockholm in 2001 and ratified in NZ law in 2004.

The bombing of the Rainbow Warrior

The bombing of Greenpeace’s flagship SV Rainbow Warrior by French Government agents in downtown Auckland on 10th July 1985 before it set sail on a new protest voyage to Moruroa shocked and outraged Kiwis. The bombing sank the Rainbow Warrior, damaging it beyond repair, and killed Greenpeace photographer Fernando Pereira.

© Greenpeace / John Miller

Greenpeace responded by helping organise a new protest flotilla to sail from Aotearoa to Moruroa in September 1985 led by MV Greenpeace, comprising SV Vega, Alliance, Varangian, and Breeze. After two of the French bombers (Alain Mafart and Dominique Prieur) were arrested by police in Auckland, they were tried, convicted and imprisoned. Following this, the French Government agreed to pay compensation to Greenpeace and to Fernando Pereira’s family.

Greenpeace used the compensation money to build a replacement Rainbow Warrior, which continued the campaign against the nuclear tests with new protest voyages to Moruroa in 1991 and 1992. The French Government finally joined a moratorium on nuclear testing in April 1992, two weeks after the new Rainbow Warrior had protested at Moruroa.

A new French Government briefly resumed nuclear testing at Moruroa in September 1995, prompting Greenpeace to send the new Rainbow Warrior to spearhead a flotilla of 32 boats that sailed to Moruroa and helped renew the global campaign against nuclear testing. In the face of massive global protest, the French Government scaled back and then halted its planned series of blasts early in January 1996, and within months agreed to sign the UN Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty and to cease the production of enriched uranium for its nuclear warheads.

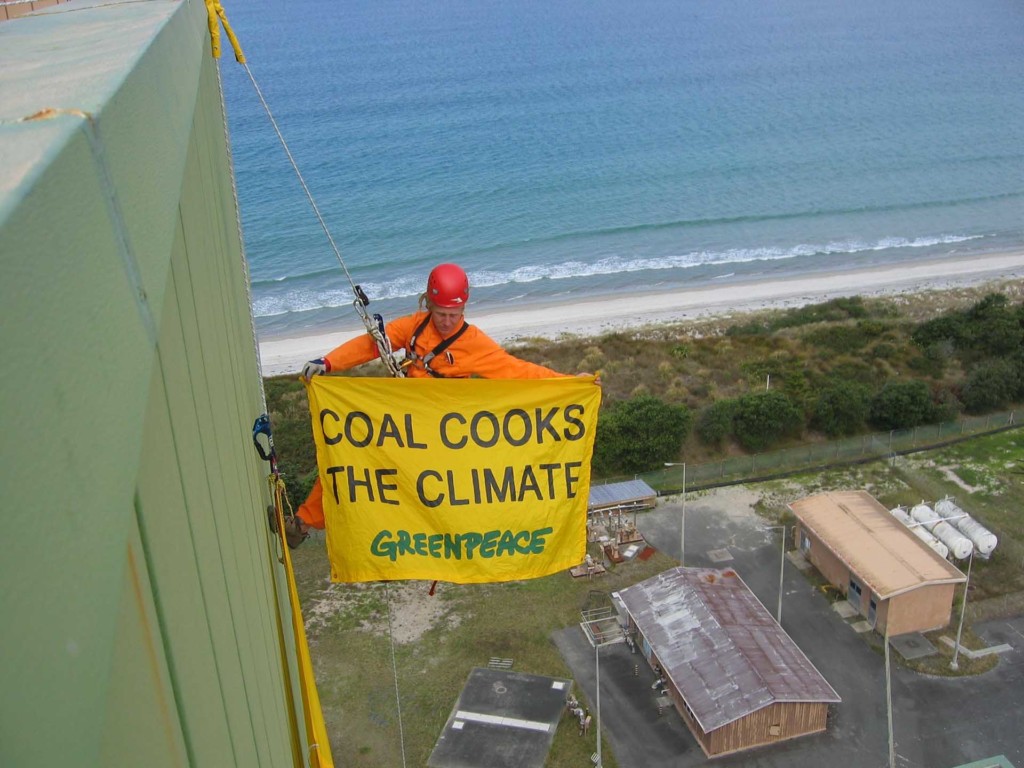

Climate change

As the threat of a nuclear war diminished after the end of the Cold War, the threat of climate change increased. Greenpeace Aotearoa launched its new climate campaign in 1990 with the aim of stopping new fossil-fuelled power stations being built at Stratford, then at Te Rapa, Otahuhu, Meremere, and Marsden Point (Marsden B).

It ran successful campaigns to stop the latter two from going ahead, negotiated a reduction in size at Te Rapa, and an agreement to phase-out an oil-fired power station in New Plymouth as a condition of a legal case opposing the proposed gas-fired power station at Otahuhu.

Greenpeace’s climate campaign also championed wind and solar power, launching its ‘Solar Pioneers’ programme in 1998 which recruited thousands of Kiwis who pledged to install solar water heating systems and solarising the electricity at the Greenpeace Aotearoa office in Auckland.

In Taranaki in 1998, a team of Greenpeace activists removed Fletcher Challenge Energy seismic testing cabling and equipment while the new Rainbow Warrior floated a giant inflatable oil barrel into the Taranaki oil fields with ‘No New Oil’ painted on it.

When a new NZ Government announced it would issue a flurry of new oil and gas exploration permits in 2010, a new Oil-Free Seas campaign was launched in 2011 following a call from Te Whānau-ā-Apanui to stop Brazilian oil giant Petrobras searching for oil and gas in the Raukumara Basin.

After a successful campaign with Te Whānau-ā-Apanui and a flotilla of small boats and their independent skippers, Petrobras pulled out of Aotearoa. Greenpeace continued to campaign in collaboration with various Iwi and grassroots organisations elsewhere, opposing new offshore oil and gas exploration within NZ’s Exclusive Economic Zone. A series of campaigns targeting Anadarko, Statoil, Shell, and OMV operations were successful, and a new NZ Government was persuaded to pass an historic ban on new offshore oil and gas exploration in 2018.

Eco-watchdog role

Over the past 50 years, Greenpeace has also carved itself a wider role as an eco-watchdog. For example, its campaigns have always had a strong focus on news media and communications to alert the public to environmental destruction, including publishing its own members’ magazine, a website, and a high-profile social media presence.

Traditionally, independent news media have reported on the actions of governments and the business sector – the classic ‘Fourth Estate’ acting as a counterweight to the power of the state and established vested interests. Greenpeace, like other NGOs such as Oxfam and Amnesty, also publishes independent reports on the issues and policies that it seeks to change here in Aotearoa, the South Pacific region, Antarctica and the Southern Ocean.

NGOs are also part of the ‘Fifth Estate’ and are able to mobilise public support to influence government decision-making and legislation, and corporate business practices. NGOs can also play an important role in strengthening civil society and holding governments and multinational corporate power to account – and in the case of Greenpeace, in protecting ‘global commons’ such as the oceans, the climate, the polar regions, and outer space, which all exist outside the jurisdiction of any single country.

Why has Greenpeace been successful?

Looking back at the history of Greenpeace in Aotearoa also raises the question, ‘What have been the main factors behind its campaign successes?’

Greenpeace is best known for using its own boats to champion environmental protection at sea, and collaborative sea-based campaigns with flotillas of small boats and their independent skippers targeting nuclear testing, nuclear ship visits, radioactive plutonium shipments, and new offshore oil and gas exploration.

Greenpeace has also been highly effective in communicating evidence-based science in the face of unsubstantiated claims made by destructive voices and denialism, especially in the areas of climate change, overfishing, and toxic pollution.

The way that Greenpeace mobilises represents a form of collective action which is more effective than disparate individuals reducing their personal carbon footprint or switching from cow’s milk to plant-based milk. This is because Greenpeace seeks to address major environmental problems such as climate change through transformative change across society and the economy.

Its track record of success has enabled it to run long-term campaigns that span decades, such as ending nuclear testing (1971-1996), commercial whaling (1975-1985), and new offshore oil exploration (1998-2021).

Greenpeace is also independent in its funding, so it has not been unduly influenced by corporate sponsors. All of its funds come from individual members and donors, plus a very small portion from grant-giving foundations and trusts.

And being part of the global network of Greenpeace offices in dozens of countries means it is part of a larger global environmental movement.

Perhaps most important of all, in a world increasingly plagued by fake news and billionaire oligarchs, Greenpeace has been able to campaign effectively with civil society allies and to help mobilise people power to protect the environment and promote nuclear disarmament and peace.

It’s an inspiring 50-year story – and the next chapter is being written right now.

Michael Szabo is the author of Making Waves (1991) and Making Waves II – a history of Greenpeace in Aotearoa (2021).