The global ocean continues to warm at a concerning rate.

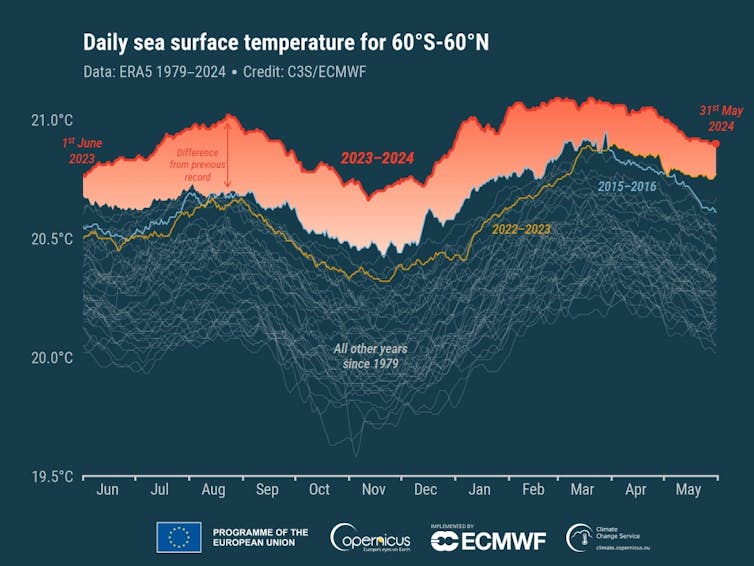

Satellite measurements of average sea surface temperatures show February this year was the highest for any month in the 45-year dataset, and the warming trend continued in May.

New Zealand’s sea temperatures are also hitting record highs. Between 2022 and 2023, oceanic and coastal waters reached their warmest annual temperatures since measurements began in 1982, according to Stats NZ data.

This warming is already threatening coral reefs – the Great Barrier Reef is the hottest it’s been in 400 years – and marine life. But it is also reshaping ecosystems at the very basis of ocean food webs.

Microscopic algae, or phytoplankton, are ubiquitous in the surface layers of the ocean. They represent the foundation of the marine food web and serve as a substantial carbon sink.

Each day, they take up more than a hundred million tonnes of carbon dioxide through photosynthesis. The carbon then either sinks to the bottom of the ocean as the microalgae dies off or is “fixed” in tiny animals that graze on the plants.

Already, scientists are observing a downward trend in this ocean production, leading to expanding “ocean deserts” and the depletion of beneficial microalgae in favour of harmful algal blooms.

Unless we act to cut emissions, these shifts in microalgal composition are projected to get worse as ocean temperatures continue to rise, globally and regionally in the waters off Aotearoa New Zealand.

Shifts in microalgal communities in New Zealand

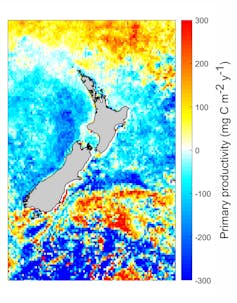

We are already seeing changes in New Zealand’s microalgal communities.

The abundance and activity of microalgae is usually measured by tracking Chlorophyll A, the pigment most plants use for photosynthesis. Recent reports by Stats NZ show shifts in microalgal biomass, with increases in some regions and declining levels in others.

Apart from these shifts in biomass, studies have also shown changes in the make-up of microalgae and reduced species diversity. This leads to stunted ecosystems which are less resilient to environmental changes, have lower productivity and capture less carbon.

Abrupt shifts in microalgal communities can drive ecosystems into altered states, affecting food webs and fisheries. Such a “regime shift” happened in the North Pacific in 1977 and 1989, with far-reaching consequences for the the entire ecosystem and salmon and halibut fisheries.

More recently in New Zealand waters, lower microalgal biomass and a collapsing food web have been implicated in the cause of “milky flesh syndrome” in snapper from the Hauraki Gulf.

Harmful algal blooms

Harmful algal blooms also appear to be on the rise in New Zealand. The toxins these microalgae produce accumulate in shellfish, and their consumption can be poisonous for people and animals and threaten the economic stability of fisheries.

Globally, the impacts of harmful algal blooms cost the blue economy more than US$8 billion per year. More than US$4 billion of this relates to human health impacts.

According to data gathered by the Ministry of Primary Industries, the rise in harmful algal blooms in New Zealand during 2023/24 resulted in the highest number of shellfish harvest closures from biotoxins this decade.

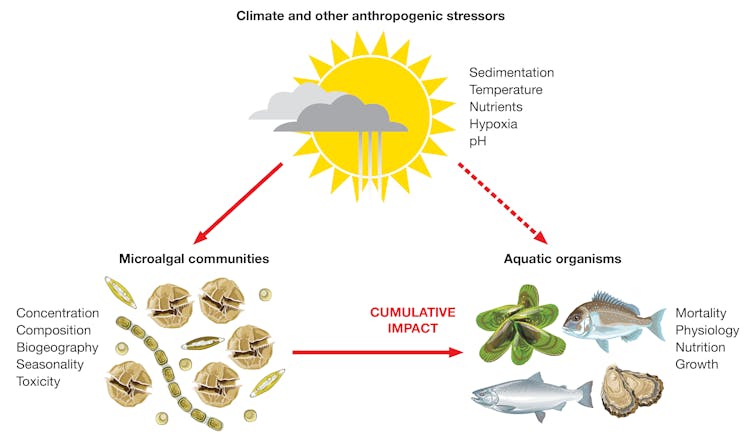

Rising ocean temperatures can accelerate the growth of microalgae that cause toxic blooms, while reducing the nutritional quality and size of microalgae species other marine organisms depend on for food.

As our research shows, microalgal toxins affect the reproduction and early life stages of shellfish species indigenous to New Zealand. New Zealand’s fisheries and aquaculture sectors, collectively worth nearly NZ$4 billion, already face harvest closures, stock losses and reduced recruitment of larvae.

There is still much we don’t fully understand about the links between climate change and toxic harmful algal blooms, but the potential for serious ecological damage was demonstrated by the 1998 bloom in Wellington Harbour, which caused a mass die-off of all marine life on the seafloor.

Toxic microalgal blooms can also kill marine mammals or make them less resilient to other stress factors, such as higher temperatures.

Addressing the challenge

Understanding how microalgal communities might change under different climate scenarios is a crucial first step.

This knowledge will help us forecast and investigate the downstream effects on the marine environment and develop effective management strategies to safeguard ocean ecosystems and public health.

Knowing when and where harmful algal blooms are likely to occur will lessen the risk for industry and enable effective restoration efforts. Improving our knowledge of the impacts of microalgal toxins on human health will enable safe recreational water use and give clarity on appropriate responses to algal blooms.

Filling these knowledge gaps is urgent. Changes in microalgal communities are already evident and will likely continue at an accelerating pace, with possibly irreversible knock-on effects on ecosystems and ocean-based industries.

From destructive fishing and mining, to climate change – the threats facing our oceans are growing greater by the day. We urgently need a network of ocean sanctuaries across the globe to protect them.

Take ActionAnne Rolton Vignier, Scientist in Shellfish and Algal Biology, Cawthron Institute and Kirsty Smith, Scientist in Algal Ecology, Cawthron Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This article is a guest post and doesn’t necessarily represent the views of Greenpeace.