The ETS, emissions pricing, agribusiness, and the politicians who taught an industry that it is far cheaper to invest in lobbying than emissions reductions

A few months out from the election, the New Zealand Government still has not introduced any kind of emissions pricing of agricultural climate pollution. This is in spite of promising to do so when they entered government five and half years ago, in spite of agribusiness being by far the biggest climate polluter, and in spite of government ministers repeatedly claiming that pricing emissions is a key policy to cut emissions. It is also in spite of a climate movement that has pushed this government hard to do the right thing on climate.

So what went wrong? How did Labour Prime Ministers Jacinda Ardern and Chris Hipkins and Green Climate Minister James Shaw kick the climate can down the road for five and a half years and do nothing substantive on New Zealand’s biggest polluting industry?

The story of the failure of this government to price agricultural emissions is part of a bigger story – it is the latest chapter in the story of how New Zealand’s biggest polluting industry successfully stopped a price on their pollution for twenty years.

Industry climate strategy

Climate-polluting industries face two basic investment choices when it comes to responding to the climate crisis. One option is to invest in methods to actually cut their pollution, which may involve significant disruption to their business model. The other option is to invest in lobbying to prevent regulatory measures that will require them to cut pollution.

Which of these two kinds of investments dominates their strategy will be heavily influenced by the response of regulators and the political system. If polluting industries believe that regulators can be pressured not to introduce regulations to cut pollution, then they are very likely to continue to invest in lobbying ahead of actual emissions cuts. However, if a polluting industry becomes convinced that regulators are determined to press ahead with meaningful rules, then at a certain point, it makes sense to move to actually cut emissions.

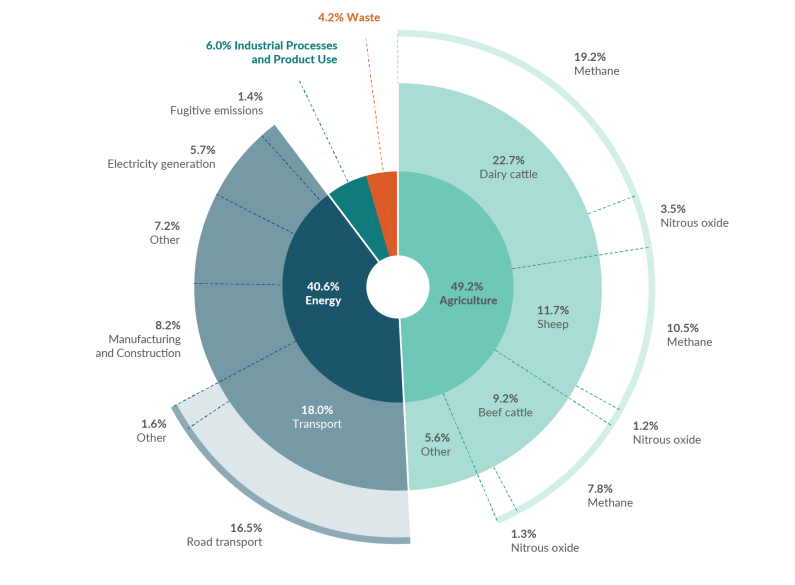

In Aotearoa New Zealand, over the last 20 years, this strategic choice has played out in the interplay between agribusiness and government over pricing emissions. About 50% of New Zealand’s emissions are from the agricultural sector – and it is the surge in dairy cows and synthetic nitrogen fertiliser that have been the number one cause of New Zealand’s 19% increase in emissions from 1990 to 2021.

Gross greenhouse gas emissions in 2021 by sector, sub-category and gas type

For decades, pricing of emissions has been identified as a critical tool to cut pollution, yet still, the sector does not face a price. There have been three separate attempts by two different governments to introduce agribusiness emissions pricing, and each time the leadership of Fonterra, Dairy NZ and Federated Farmers have fought off the proposals – putting their profits ahead of a stable climate.

This is a story about how the leadership of a highly polluting industry invested in lobbying to block policy that would have required them to face a price on their emissions. It is the story of how a series of governments rewarded that behaviour and locked in an agribusiness leadership that is not only determined to block action on climate but can show to their constituency that investing in political lobbying works. Anyone in the sector who has argued for meaningful attempts to cut emissions has been sidelined by those who can legitimately show that predatory delay and lobbying has been a successful strategy.

Climate denial and predatory delay: 2003 – 2017

The first attempt to place a price on agricultural emissions was back in 2003 when the Government tried to introduce a levy to fund research to cut emissions. The agribusiness sector and right-wing parties mobilised against what they called the ‘Fart Tax’, and ultimately the Labour Government backed down. The sector was led by climate deniers who were rewarded for their efforts to block climate pricing.

The second attempt came in September 2008 when the New Zealand Parliament passed the Climate Change Response (Emissions Trading) Amendment Act, which set up the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). The stated aim of the ETS was to put a price on carbon pollution to encourage businesses and consumers to cut their pollution. After considerable lobbying from agribusiness, agriculture’s entry into the ETS was delayed until 2013 under this legislation. This five year delay provided ample opportunity to potentially stop it, especially as there were two elections between the passing of the law and when agriculture would come into the ETS.

The ETS legislation was a compromise between Labour, New Zealand First and the Green Party. It required all three parties to vote for the legislation for it to pass.

I was the Co-Leader of the Green Party at the time, and we were very uncertain as to whether we should provide the necessary votes given that we supported a policy of a straightforward carbon tax, rather than a trading scheme. We also believed that while pricing was one part of the climate policy mix, it wasn’t the only part or even the most important part. The ETS was a very weak policy, but in the end, we voted for it so as to have something rather than nothing. The problem was that as the ETS was even further weakened over the years, it remained in place and gave the appearance that the government had some kind of climate policy when in reality, they didn’t.

As it came to pass, agribusiness didn’t need to wait for two elections before they could dispose of the attempt to make them pay. In December 2009, only a few months after the legislation was passed, there was a change of government, and the new John Key National Party-led Government quickly moved to weaken the ETS. In November 2009 with the support of the Māori Party, the National Government passed the Climate Change Response (Moderated Emissions Trading) Amendment Act which further delayed the entry of agriculture into the ETS until 2015.

A further amendment was made to the ETS in November 2012 when the National Government passed the Climate Change Response (Emissions Trading and Other Matters) Amendment Act which delayed the entry of agriculture into the ETS indefinitely.

A decade after the defeat of the ‘Fart Tax’, the industry strategy of investing in lobbying, combined with a strategy of predatory delay, produced the desired result – there was no pricing of agricultural emissions and no serious policy to cut emissions out of the sector. The leadership of the sector was vindicated.

A window opens for action: 2017-19

This situation of predatory delay remained the status quo until the 2017 election, which elected a Labour, NZ First, Green Party Government. The Labour leadership campaigned on a platform of taking action on climate change and had a policy of bringing agriculture into the ETS.

As part of the October 2017 Coalition Agreement between Labour and NZ First, agriculture was to enter the ETS, if the new Climate Change Commission recommended it, but it would only have to pay for 5% of its emissions. NZ First was always opposed to putting agribusiness into the ETS so it took serious negotiations and concessions in other areas to get this policy into the Agreement. In April 2019 the interim Climate Commission did recommend that agriculture enter the ETS, at least as an interim step.

It seemed that after 16 years of effective lobbying to stop a price on their emissions, 16 years of predatory delay by agribusiness, agriculture was about to finally enter the ETS and face a small price to encourage them to cut their climate pollution.

It seemed that the reward structure established by successive governments was about to change and those in the sector who had fought all efforts to seriously cut emissions would face a defeat. This could open the door to a new set of leaders who wanted to lead a low emissions food producing sector.

But… just when it seemed that agribusiness would finally have to invest in cutting emissions rather than invest in lobbying to stop policy that would make them cut emissions, they came up with a masterstroke of predatory delay – a new strategy called He Waka Eke Noa, which roughly translates as ‘we paddle the canoe together’.

In the He Waka Eke Noa proposal, agribusiness switched tactics away from climate denial. They said they now believed that we needed action on climate, and they were willing to accept some kind of climate pricing. However, they argued, it was just not the kind of pricing that the government proposed, not the ETS. They were no longer overtly adopting the narrative of climate denial, rather they switched to the need to seek consensus between government and agribusiness as a reason for not introducing prices – at least not right now and not via the ETS.

The new strategy was a kind of greenwashing predatory delay and it was to prove effective beyond their wildest dreams.

Greenwashing predatory delay

In October 2019 agribusiness and the government announced a joint proposal called He Waka Eke Noa. It was a five-year scheme to once again delay emissions pricing to 2025 while they developed an industry-led emissions pricing system.

The industry-led plan would have the point of obligation for emissions pricing at the farm rather than the processor. The ETS had a processor-level point of obligation that created a concentrated financial incentive for processing companies like Fonterra to drive carbon efficiency from their farm suppliers in order to cut the cost of carbon. The farm-level point of obligation would mean that tens of thousands of farm managers would need to manage their emission liabilities with the government rather than a dozen large-scale processing companies doing the work. It was a recipe for complexity in the system, with much higher compliance costs for individual farm managers who had fewer resources for the scheme’s required administration. In short, it was a proposal that would take years to develop, was likely to be highly complex, and guaranteed to generate loads of farm-level opposition. It was, in summary, a proposal made in heaven for those intent on predatory delay.

In announcing this decision to cave in to industry lobbying pressure and move away from the ETS, the Government said that if industry did not develop a satisfactory plan to price agricultural emissions, then they would be put into the ETS by 2025 or even as early as 2022. This was the stick that was supposedly hanging over He Waka Eke Noa to ensure that the industry took it seriously. But 2025 was a long way away, and once again, the industry was presented with a two-election delay before any potential pricing might come into play.

The first draft HWEN proposal for emission pricing outside the ETS didn’t come out for two years. In November 2021, the agribusiness representatives released two options for pricing, both of which cut emissions by less than one percent. This was plainly not a serious effort to cut emissions and there was quite a bit of criticism.

The final HWEN proposal for emission pricing came out in June 2022. The methane emissions reductions from the price proposal were once again less than 1%. But this time they took greater care to hide this miserly reduction by adding imagined emissions reductions of 3% to 4% that came from as yet unknown technological developments. To these ‘silver bullets’ they added the emissions reductions from the freshwater regulations (which Federated Farmers were actively challenging) and the methane emissions reductions from the waste sector, to claim a ten percent emissions reduction. The ten percent headline number was the PR handle the government needed.

The government responded to the HWEN proposal in October 2022 and released its draft proposed approach to pricing agriculture emissions. By this time, it was five years since the coalition agreement to put agriculture into the ETS, three years since the start of HWEN, and, vitally, only about a year out from the election. The delay tactic was delivering.

The Government’s October 2022 proposal was a version of the farm-level HWEN proposal. In addition, it provided $485m in government subsidies to help the industry reduce its emissions- paid for in part from ETS revenues paid by other businesses and consumers, an ETS that agribusiness insisted it must not be part of. This was on top of a further $517m in subsidies to the sector via the Sustainable Fibre and Food Fund. But still, the proposal was attacked by agribusiness because agribusiness didn’t have full control of the pricing mechanism, amongst other complaints.

The only leverage that the government had over the sector was the threat of putting them into the ETS as a backstop if HWEN did not deliver. However, Climate Minister James Shaw said he didn’t support putting agriculture into the ETS, leaving a version of the complicated HWEN scheme as the only option, and hence the government with no power over the sector.

Federated Farmers, realising their strong position, walked out of He Waka Eke Noa, and the government backed down further and made new concessions to the sector. Dairy NZ demanded changes, Fonterra was not happy, and the sector was united in opposition. This was in spite of the reality that the government’s draft scheme was almost identical to that proposed by HWEN.

On December 21 2022, four days before Christmas in the middle of the silly season, the government released its final proposal on pricing agricultural emissions outside the ETS. The government promised the lowest price possible, fixed for five years, with all revenue recycled back to industry. It was a weakened version of their earlier proposal though it still included the added sweeteners of millions of dollars in taxpayers subsidies to agribusiness, paid for through taxes and ETS revenues. The scheme was essentially a version of HWEN, which Treasury had concluded would cost taxpayers dearly and not cut emissions.

Yet still, Beef and Lamb was unhappy with the whole thing and sought further indefinite delay. Federated Farmers opposed the Government’s plan and Dairy NZ opposed key elements of it. After four years of delay, after the government adopted the industry’s own plan, industry now didn’t support it, in spite of all the promises made at the start of the process.

As if to make clear just how superficial was agribusiness commitment to climate action, the President of Federated Farmers went on radio to say that maybe climate change was real but we would only know in 50 years and he didn’t accept the methane reduction targets anyway. A few months later he announced that he was standing as a Parliamentary candidate for the climate-denying Act Party, following in the footsteps of other leading members of Federated Farmers.

Government said that they would make final decisions in early 2023. Indeed, you would think the climate-charged wreckage caused by Cyclone Gabrielle in February 2023 would seem to have added pressure to take action on cutting emissions.

But as of May 10 2023, the Labour Government has not announced any decision. We are now only five months away from the general election, and agribusiness representatives are calling for all decisions to be delayed until after the election in the hope that a bit more predatory delay will once again remove the need for them to face a price on their emissions.

It has been twenty years since the first attempt to price agricultural emissions, it is fifteen years since the introduction of the Emissions Trading Scheme, ten years after agribusiness was first scheduled to enter the ETS, nearly six years after the Labour-NZ First coalition agreement to bring agriculture into the ETS and four years after the launch of He Waka Eke Noa to supposedly develop a consensus between industry and government on pricing agricultural emissions. At every step of the way, agribusiness lobby groups opposed these attempts.

He Waka Eke Noa was simply the latest in a long string of delay tactics drawn from the long list of industry delay strategies. Agribusiness never had any intention of agreeing to the pricing of their emissions.

A failure of industry and political leadership

The leadership of New Zealand’s agribusiness sector has been consistently appalling on environmental issues and has fought every attempt to protect the environment, whether in freshwater or climate. They have denied the basic science, focussed on short-term profits, simply not told the truth about their true intentions, and lacked the imagination to see that the world is changing.

We have agribusiness leaders whose strategy of climate denial, greenwashing and predatory delay has been successful in blocking pricing efforts to change their industry for decades. The success of the leadership in Fonterra, Dairy NZ and Federated Farmers in blocking these measures has left the New Zealand food production sector woefully inadequately placed to deal with climate change, one of the biggest threats to the planet and their industry. For those at Fonterra who do understand climate science, they are taking an approach of being a free rider – yes they understand the need to cut emissions, they just don’t want to have to do it at Fonterra, they want other companies to cut emissions. And if everyone is a free-rider then nothing will change.

I am very familiar with all this as I have engaged with their leadership and membership on many occasions over many years. Their position is not amenable to change through consensus for Upton Sinclair’s simple reason: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” I remember giving an address to the Federated Farmers annual conference in 2011 where I presented the wealth of evidence on the science showing that agricultural intensification was causing water pollution, scientific study after study. The questions from the floor that followed were simply a litany of denial. I have given similar speeches to Fonterra and met with the leadership of Fonterra, the Feds and Dairy NZ on countless occasions. They are not all bad people, they simply have a profound financial incentive to protect their position and will not change unless the government (or potentially their markets) forces them to change.

But while the sector as a whole bears the responsibility for that, it is also true that the Government has helped make them what they are by not standing up to them. By caving in to industry pressure time and time again, the Labour, National and Green parties have taught the agribusiness sector that it makes more sense to invest in lobbying and pressuring the Government to block regulation and pricing than it does to actually embrace low emissions food production.

Change or Consensus

In that sense, it is also a story about a Labour and Green Party leadership that exercised a deliberate blindness in order to avoid a confrontation with the most powerful sector in the country. The idea that the government should back down on bringing agribusiness into the ETS in order to find consensus with the current agribusiness leadership on pricing agriculture emissions was plainly not credible. The sector obviously never intended to sign up to a real pricing plan. One can only assume that Labour and the Greens signed up to this charade because it meant they didn’t have to confront the political power of agribusiness in Aotearoa New Zealand.

In parallel with this political lack of courage, the leaders in Labour and the Greens espoused a theory of change through consensus. We were told that consensus with the polluting industries was essential to making progress on climate. James Shaw, at the announcement of He Waka Eke Noa, said ‘nothing about us without us’ in reference to the need to get the consent of the polluting industries before introducing agricultural emissions pricing. But this just isn’t true. No serious change happens without opposition. Whether it is votes for women, nuclear-free NZ, eliminating CFCs and saving the ozone layer – these campaigns were won by overcoming the opposition of existing power-holders and polluters, who benefitted from the status quo. Making climate policy hostage to the agreement of climate polluters is simply saying you don’t intend to do anything serious about climate.

At the time of the announcement of He Waka Eke Noa in 2019, I called it a ‘sellout’ by Labour and Greens on climate change. I knew that once the leaders of Fonterra, Federated Farmers and Dairy NZ got Ardern and Shaw to back down on this core issue, they would know they had the upper hand. And then they would simply drag the whole show out until it was too late. And so it has come to pass. The reality is that serious change never happens through consensus – the old order always resists change.

The climate movement is the only way to fix this thing now. Real change always comes out of civil society – government and business follow kicking and screaming. We fought hard to win the fight over new oil and gas exploration in Aotearoa New Zealand and eventually, the political process caught up. Now we need to win the fight over the transformation of the global food system for both climate and biodiversity reasons.

-

Ecology and habitability

Russel Norman’s address to the Environmental Defence Society Conference on 24 March 2023

-

The ten billion dollar lie at the heart of the New Zealand Government’s climate policy

The New Zealand Government has made a big promise on the international stage to cut New Zealand’s emissions by a 147 million tonnes over the decade of the 2020s. But the truth is that

-

From climate denial to greenwashing

Why is greenwashing the biggest challenge that the climate movement faces at the moment. How did we get here?

Join our call on the Government to go further than the Climate Commission’s inadequate recommendations and cut climate pollution from NZ’s biggest polluter: industrial dairying.

Take Action