Deep sea mining is the practice of mining metals and minerals from the seabed. It’s an extremely destructive form of mining that would damage the oceans beyond repair, threatening their ability to help fight climate change.

Here’s everything you need to know:

What is deep sea mining?

Deep sea mining is the practice of removing metals and minerals from the ocean’s seabed. Thousands of metres below the surface, deposits of these metals and minerals like manganese, nickel and cobalt have built up on the seafloor into potato-sized nodules over millions of years.

To mine these metals, gigantic machines weighing more than a blue whale would scoop deposits from the deep ocean floor. They’d then pump the mined material up to a ship through up to several kilometres of tubing. Sand, seawater and other mineral waste would then be pumped back into the water.

PETITION: Stop deep sea mining

Deep sea mining is a very new industry. Apart from a few small tests, no actual mining has happened yet. However, the companies involved are preparing to start full-scale production. And governments are deciding whether to let them go ahead.

What are the problems with deep sea mining?

Like mining on land, deep sea mining is extremely destructive. But mining the ocean floor is hugely risky for so many reasons – because the impacts are far more difficult to predict.

The full environmental impacts of deep seabed mining are likely to be highly damaging, both within and well beyond the areas being mined.

Carbon stores

The oceans are facing more pressures now than at any time in human history, and are severely threatened by overfishing and the climate crisis. Our oceans absorb and store carbon, and give more than three billion people their livelihoods.

The metal and mineral deposits themselves are an important habitat for marine life. The nodules containing these metals are found 4,000 metres deep in the Pacific Ocean – where the ghost octopus lays its eggs.

The deep ocean is hugely important in the fight against climate change. It absorbs and stores over 90% of the excess heat and approximately 38% of the carbon dioxide generated by humanity. Risking this delicate system during a climate emergency could have irreversible impacts on the climate.

Sediment plumes & noise pollution

Deep sea mining companies haven’t proven that they can do it safely (or even at all). They’ve got a huge piece of machinery stuck on the deep sea floor. Their tests are already creating plumes of pollution in the Pacific. These plumes can spread for many, many miles – potentially harming all sorts of ocean life.

The noise from deep sea mining will travel far, and be extremely disruptive to marine mammals that use sound as a primary means of underwater communication and sensing.

Global opposition

Several countries – including Germany, France, Spain, Chile, New Zealand and several Pacific Island nations – think deep sea mining is risky for marine life. They are proposing a pause or a ban on issuing licences. The UK should join these governments and support a global moratorium. A moratorium is a temporary ban. They’re used to give regulators more time to gather evidence and understand the risks of a proposed activity..

World leaders have finally agreed a Global Ocean Treaty. Mining the ocean floor will create further stress on the ocean at this crucial time for ocean conservation.

Why do companies want to mine the seabed?

Companies went to extract metals from the seabed to sell them to industries that need increasing amounts of manganese, cobalt, nickel and copper for one simple reason: to make a profit. To them, the sea is just another frontier to exploit for money.

Mining companies are saying they need to mine the seabed for the metals needed to make batteries for the energy transition away from fossil fuels. But mining one of the last untouched ecosystems on Earth will never be “green”.

There are far better alternatives to deep sea mining. Improving recycling and reducing dependence on cars will help use metals more efficiently. And mining the seabed won’t stop mining on land (or for that matter, the continued extraction of fossil fuels).

Where is it happening?

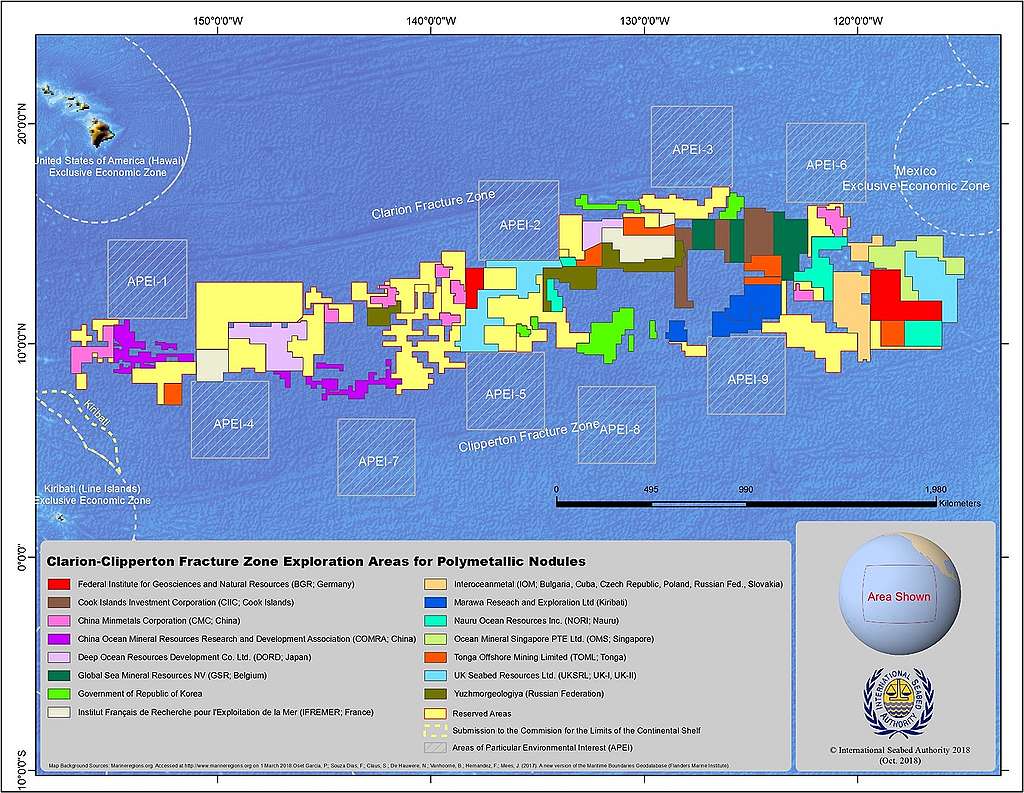

Although test mining is underway, commercial deep sea mining is not yet allowed by international law. The International Seabed Authority has granted 31 contracts for exploration of opportunities. These cover over 1.5 million km² – an area four times the size of Germany.

Most of these contracts cover exploration for deposits in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), an area in the Pacific Ocean across the equator, between Hawaii and México. The area is rich in potato-sized mineral deposits loaded with copper, nickel, manganese and other metals. They lie on the deep sea bed in huge fields.

In July 2021, the government of Nauru announced intentions to begin deep sea mining, partnering with a Canadian company. The announcement triggered an obscure “two year rule” in international law meaning that by July 2023 mining can begin, with whatever rules are in place – or lack of them.

Who is involved?

The secretive deep sea mining industry is run by mining companies headquartered in the Global North‘Global North’ is a broad term for wealthier countries. It’s used in contrast with economically poorer countries that make up the ‘Global South’., in partnership with governments. Mining companies, like The Metals Company, appear to be pushing countries to help them open up a new frontier for mining the ocean.

Countries can sponsor companies’ applications for exploration and mining contracts to the International Seabed Authority, or ISA.

The ISA was founded in 1994 through the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and is headquartered in Kingston, Jamaica. It makes the rules for deep sea mining, because the seabed is outside of countries’ national borders.

The ISA’s officials also seem to be pushing for companies to be allowed to start deep sea mining. This is despite the ISA’s mandate to protect the global oceans, and only allow mining to start if it can benefit humanity.

The UK government sponsors two exploration licences, both granted to UK Seabed Resources. These cover over 133,000 square kilometres (an area bigger than England) in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. The UK’s licences cover a larger area than any other country, except China.

Who would be affected by deep sea mining?

Vulnerable coastal communities, especially in developing countries, will pay the highest price.

Peer-reviewed science is already showing that deep sea mining carries a virtual certainty of causing lasting damage to deep sea ecosystems. This means potentially severe impacts on countries and communities that depend on the Pacific Ocean.

The impacts of mining the deep sea could seriously affect the fish populations that provide food and livelihoods for many Pacific communities, who are Indigenous Peoples. They have profound cultural and spiritual ties that many remote island nations have with the sea.

The nodules containing the metal deposits have taken millions of years to form and are one of the keystones of deep sea life. When they are gone, they cannot be replaced; nor can the ecosystems that thrive around them. This would cause disruption all the way up the food chain that Pacific communities – and all of us – rely on.

Mining these deposits would destroy biodiversity and habitats which have far reaching benefits to all life on Earth that aren’t fully understood. The deep ocean is a vast reservoir of biodiversity, from glowing sharks to armoured snails, with new species being discovered every year.

Opposition to deep sea mining

International opposition to the deep sea mining industry continues to grow.

- Businesses including BMW, Volvo, Google and Samsung have committed to avoid ocean-mined minerals.

- Many governments are now calling for either a ban or moratorium, including France, Spain, Germany and New Zealand. The UK is becoming increasingly isolated in not calling for a ban or moratorium.

- Scientists around the world have also opposed the industry. More than 700 from 44 countries signatories on an open call to pause deep sea mining.

We need to stop deep sea mining

This is a once in a generation opportunity to stop profit-seeking companies from destroying the oceans and a crucial defence against climate change.

Imagine if we could go back in time and stop dangerous oil drilling. Stopping an industry before it has a chance to start will undoubtedly prevent further environmental and climate catastrophes.

Greenpeace wants to prevent the destructive deep sea mining industry from ever getting started in the oceans.

It’s time for New Zealand to take a stand. Join our call on the New Zealand government to back a global moratorium on seabed mining.

Take Action