Wendy Reid, a former Greenpeace Board member, remembers back to what it was like growing up on a mixed dairy, pig, sheep farm.

I grew up on a farm seven miles out of Waihi in the Bay of Plenty, up an unsealed road into the bush. At that time (in the 1950s/60s) there were seven farms up that road.

My father was just 18 years old when he first went onto this 400 acre (160 hectare) bush/hill country farm in 1932. His father had bought the block for a pound an acre. There was only one small clearing of bracken fern (where he built a shack to live in). The rest was all virgin native bush.

He cleared the native bush for pasture – but left bush on the roadside, along the gullies, around waterways and water sources. By the time the farm was sold in 1974 he was farming 200 acres of grassland with the remainder still in bush.

We were a family of six children and it was really subsistence living. We had our own dairy herd of 40 cows, as well as pigs, hens, and 400 sheep. We had a huge fruit and vege garden that sustained us.

The farm was connected to an electricity power supply around 1954 and we got our first farm tractor about the same time.

All of us kids helped out with the jobs, it was just part of our life, sweeping down the cow shed every day. Feeding bobby calves, mustering sheep, feeding chickens, docking lambs, being roustabouts in the woolshed. We washed the various components of the stainless steel milk separator (without slicing our fingers).

The milk separator machine separated the cream from the skim milk. The cream was sold and the skim milk fed the pigs. It was a more circular system where nothing could be wasted.

We left the cream can at the mailbox to be picked up. A horse-drawn cart took the milk off to the dairy factory in Waihi. At that time, there were lots of small dairy cooperatives around the country – true cooperatives, not like the one monopoly Fonterra ‘cooperative’ today.

Our cream was turned into cheese and butter. No one was making huge money, it was less hierarchical, and there was a sense of shared control. The stocking rate wasn’t very high in those days, just one cow per two acres.

It may be hard to imagine now but we had very limited cash. We got a monthly ‘cream cheque’ and an annual ‘wool cheque’ and that was it. We sold our wool just once a year and got the sum all at once. If things got really tough we sold a pig.

Farmers in those days didn’t permanently employ or pay workers in regular cash wages as they seldom had any cash to spare. It was more of a piece meal arrangement used when extra labour was required for specific farm tasks.

The exchange for a single man could be free board and lodgings in return for labour; or free mutton and other farm or garden produce for the families of married men who rode a horse ‘to work’ and lived elsewhere. Over time the concept of share-milking with a farm cottage provided for families on the larger dairy farms, became the norm.

Everyone on our road helped each other out for the big jobs. For example, we all did the haymaking together. It was an annual job at summertime when we would go from farm to farm collectively. There was no money paid out.

I clearly remember the spreading of superphosphate as a manual job. We used the chemical fertiliser to make the pasture and poor soils productive. But at that time, it was spread by hand, which by its nature limited the amount that was used. The person spreading it had a sacking tray around his neck. He filled it up and walked up and down, spraying it by the handful. The fertiliser was treated as a precious commodity as it was so expensive.

Things really changed as I grew up

From selling locally, our cooperatives were exporting more and more. Production scaled up as we started having to compete globally, and more farmers moved to dairy.

To be able to meet dairy company demands and to make a profit, farmers needed more cows and expensive new machinery such as herringbone sheds, which doubled the number of cows that could be milked at once. Instead of cream carts pulled by horses, the milk tankers came and took away whole milk.

Dairy companies now required milk farmers to put down driveways and bring roads up to the standards required for the milk tankers. Today it’s rotary sheds that are the shed of choice, able to milk herds of 2,000 cows and be operated by individual milkers.

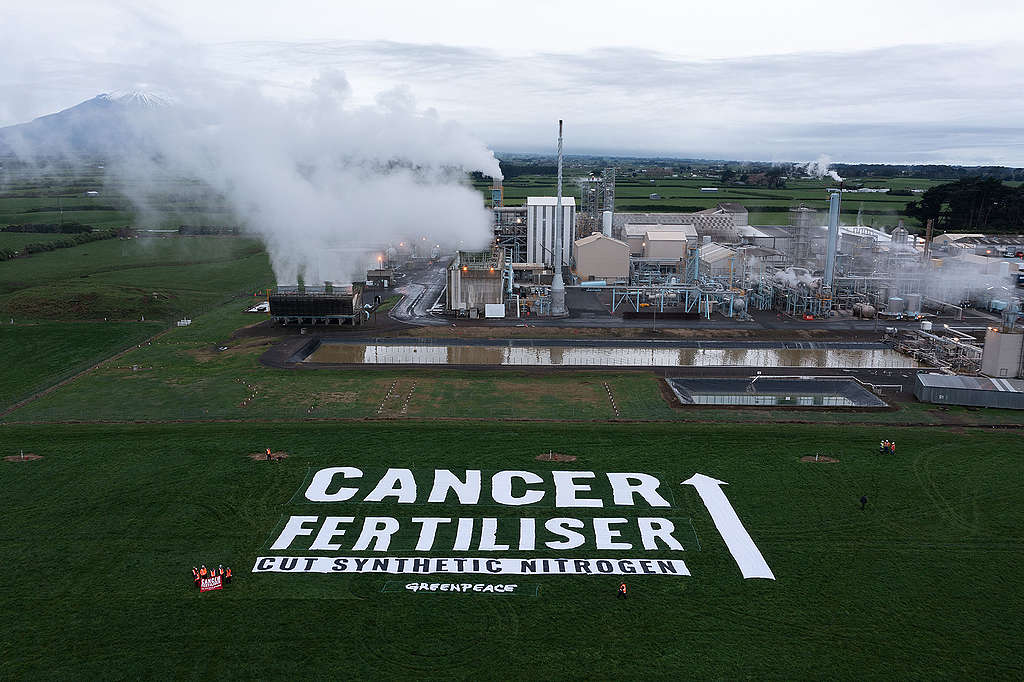

As farming intensified, farmers were pressured to use synthetic fertiliser in ever increasing amounts to grow the grass needed to feed the bigger herds. The fertiliser was applied by plane, which we call aerial top dressing. Aerial top dressing was pioneered in New Zealand, and has been the main factor in the development of hill-country farming. This is more indiscriminate and spread broadly, as a result affecting bush and waterways. The chemical nitrates filter into the environment through the soil and water.

From people who were used to living without cash, farming families also got used to big payouts from the dairy companies and started buying nice houses and cars and expensive farm machinery. I think they’ve become consumers themselves – an expensive house and having to have all the “toys” is a trap for all of us.

My dad used to say it was the beginning of ‘farming the farmers’

Dairy farming has expanded hugely over the decades. In 1945, New Zealand had a cow population of 1.7 million. In 1969, there were 2.3 million cows; in 2011 it went over 6 million cows. Nitrogen fertiliser use has skyrocketed, increasing 635 percent between 1991 and 2019.

As the number of cows increased, the number of farmers went down. In 1945 there were 40,000 farmers and 409 dairy factories; in 1969 25,000 farmers, and 229 dairy factories. There are now around 11,000 farms. The bigger farms, bigger herds, efficiencies of production, and less need for farmers has drained our rural communities. Now a single buyer, Fonterra, substantially controls the market as the major purchaser.

All the new investment put farmers in debt, and put them on this treadmill they can’t get off. Debt in the dairy sector tripled from 2000 to 2015, and then shot up between 2015-2020 – it’s now at $40 billion.

In 1984 the Government removed subsidies – ever since the Great Depression the Government had guaranteed farmer incomes. This meant farmers were under more pressure to chase the biggest profits. It accelerated the move into dairy farming, no matter what kind of land and soils farms were on.

And the whole system scaled up again with the creation of Fonterra in 2001, to create one major processing and marketing cooperative. Laws were passed to liberalise exports, with the aim of making New Zealand products more competitive on the world market.

Fonterra is now responsible for a third of international dairy trade. It is New Zealand’s biggest company. It is the world’s single largest exporter of dairy products.

The word ‘cooperative’ has been taken over by this corporate monolith that dominates the market.

Honestly, in my view Fonterra is a blight on Aotearoa. It is singularly profit driven and has become a tough regime for farmers to operate within. It’s devastating the natural environment with no qualms, and then saying they are the ‘most efficient’ in the world. Rivers are unswimmable because of the impact of agriculture, and methane emissions from the dairy sector are destabilising our global climate.

Who farms the farmers? Fonterra.

Farmers have limited choices. There is increased suicide and mental health difficulties among the farming community. The public distrusts the farming sector more and more because of the choices they’ve been forced to make, and the resulting poor environmental outcomes.

When our farm was sold all the remaining bush was clear-felled. As a result, the new owners lost their water supply and had problems with erosion as the soil washed away. Ironically, they had to replant, and did it with exotic trees.

We have to choose another way. We have to boost the transition to healthier ways of living and farming. We can produce food using techniques that build soil fertility and value water for its life giving properties, not a dollar value. We need to end the use of synthetic fertilisers. We need to relearn how we enhance the natural fertility of the land and work as part of the natural ecosystems. We need to change our expectations, and not chase after the big international bucks.

We need to create a better quality of living for everyone, including food producers. Maybe it’ll be smaller in scale, but we’ll live better, and farmers will have choices. Our ecosystems and biodiversity will benefit and as a country we will become more resilient.

Join our call on the Government to go further than the Climate Commission’s inadequate recommendations and cut climate pollution from NZ’s biggest polluter: industrial dairying.

Take ActionWhat is Fonterra?

In New Zealand, as in most Western countries, dairy co-operatives have long been the main organisational structure in the industry. The first dairy co-operative was established in Otago in 1871.

Fonterra was formed in 2001 from the merger of the two largest co-operatives, New Zealand Dairy Group and Kiwi Co-operative Dairies, together with the New Zealand Dairy Board, which had been the marketing and export agent for all the co-operatives.

- Privately owned shareholder

- 10,000 owners

- $1 billion profit

- 20,000 employees globally

- Fonterra is New Zealand’s biggest company. It’s the world’s largest exporter of milk products. It’s one of the largest dairy manufacturers in the world.

- New Zealand sells 95% of its dairy products abroad

- Europe is the most important market for butter, the US for casein (a protein supplement), Japan for cheese, and Asia for whole milk and skim milk powder.

- Fonterra’s global milk supply comes from farms in New Zealand, Australia, Chile and China.

- Fonterra is New Zealand’s biggest climate polluter. Fonterra alone produced almost a fifth of New Zealand’s total greenhouse gas emissions last year.