The depths of our oceans hide a unique living world that we barely understand – but these mysteries are already under threat from a controversial new industry: deep sea mining.

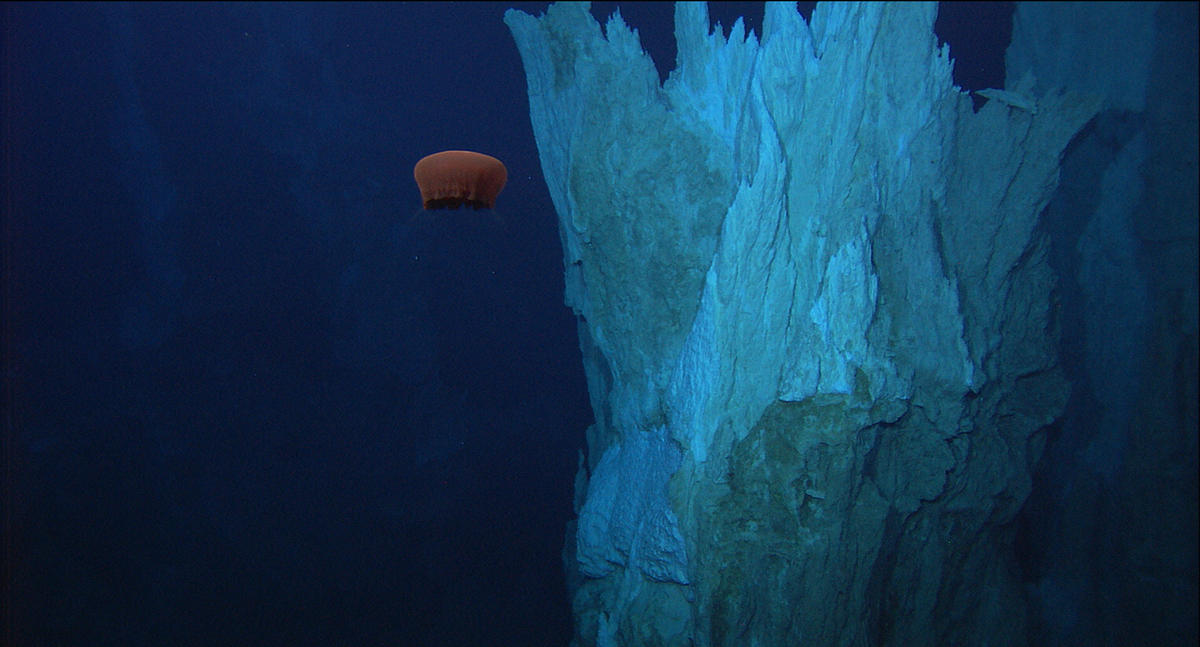

Hercules captured this image of a deep-sea jelly fish, possibly Poralia rufescens, undulating several meters above the seafloor just south of the IMAX vent at Lost City, Atlantic Ocean, Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Science Party; NOAA/OAR/OER; The Lost City 2005 Expedition. Creative commons CC BY 2.0

A handful of companies and governments are planning to send monster machines deep beneath the waves, disrupting sensitive and unique habitats to extract metals and minerals. While licences have been granted to explore for deep sea mining in over a million square kilometres of our global oceans, no deep sea mining is happening – yet.

Sending gigantic mining machines designed to bulldoze and churn up the seabed is clearly a very bad idea. Want to know how bad? Here’s five reasons why deep sea mining will only get our planet into deep trouble.

Reason 1: Very bad news for wildlife

Scientists are warning that plundering the seafloor with monster machines risks inevitable, severe and irreversible environmental damage to our oceans and marine life. You only have to look at some of the names of recent research papers: ‘Deep-Sea Mining with No Net Loss of Biodiversity – An Impossible Aim’.

In the deep sea, we find underwater mountains that are oases for sea creatures, ancient coral reefs and sharks that can live for hundreds of years. These are among the longest living creatures on Earth, which makes them particularly vulnerable to physical disturbance because of their slow growth rates. Researchers estimate that harm to wildlife from mining “is likely to last forever on human timescales”.

The spiral tube worm, or Sabella Spallanzanii, lives in membranous tubes, often reinforced by the inclusion of mud particles and has a feathery, filter-feeding crown that can be quickly withdrawn into the tube when danger threatens. Greenpeace is in the Azores with a team of scientists to survey and document deep sea life.

As if the total destruction of their homes wasn’t bad enough, machines cutting the seafloor will create sediment plumes, which could smother deep sea habitats for kilometres. The ships on the surface for the mining operation could also release toxic vapours into the water, harming many ocean species for hundreds or even thousands of kilometres.

And it’s not just pollution wildlife have to worry about. Noise generated by churning machinery risks harming and disturbing marine mammals like whales, while floodlighting areas of the dark deep ocean could cause permanent disruption to sea creatures adapted to very low levels of natural light.

Reason 2: Extinction of creatures found nowhere else on the planet

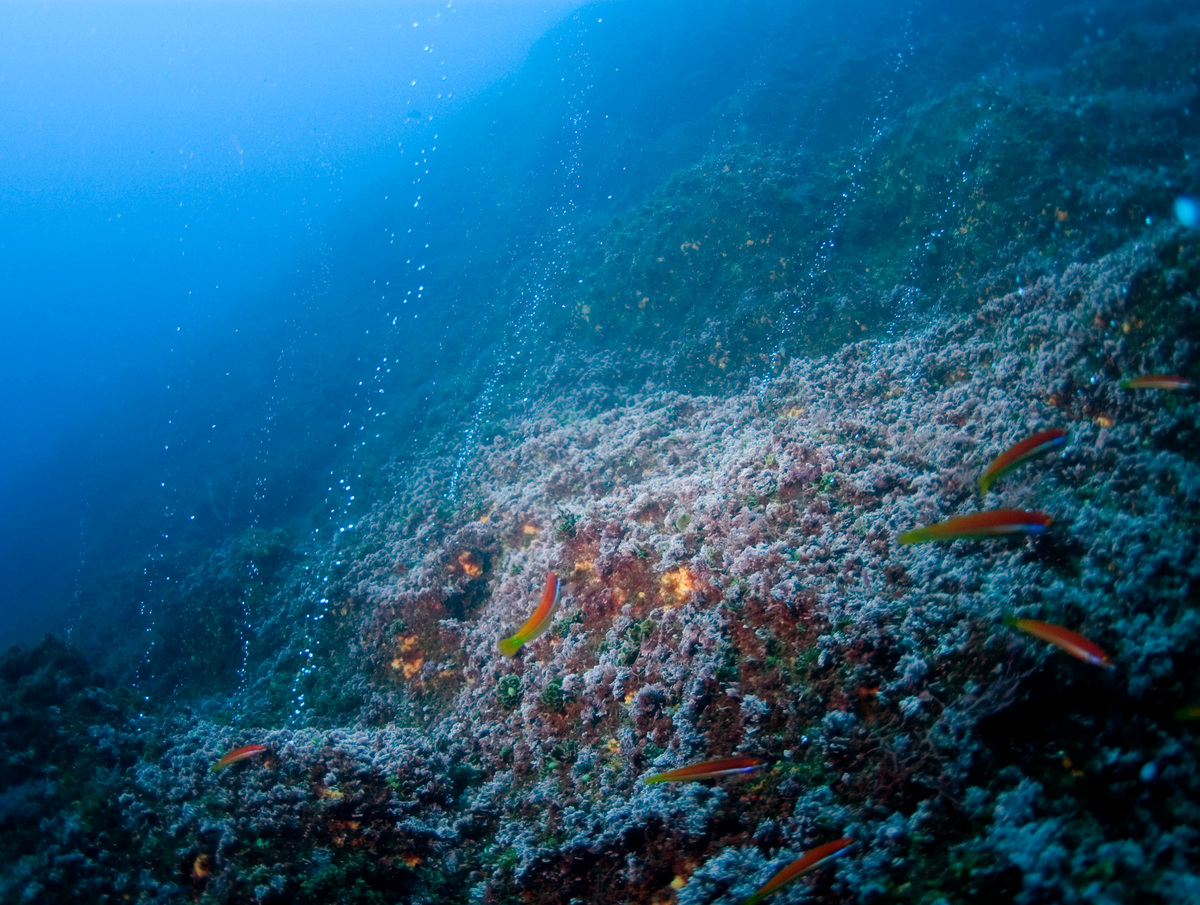

The creatures of the deep sea, specially adapted to live in the extreme alien environment of the ocean depths, almost look like something from another planet. From ‘zombie worms’ discovered in 2002, to a transparent anemone that can eat worms six times its own mass, the deep seas are full of weird and wonderful creatures. At one of the target sites for mining, 85% of the wildlife living around hydrothermal vents are found nowhere else in the oceans.

The mauve stinger jellyfish, or Pelagia noctiluca, grows up to 10 centimeters in diameter. When a calm sea is disturbed by a passing boat or dolphin at night, this jellyfish is able to produce flashes of light. Greenpeace is in the Azores with a team of scientists to survey and document deep sea life.

Shockingly, licences have already been granted to explore for mining potential at vents, including the incredible Lost City in the middle of the Atlantic. Mining machines grinding up and destroying the habitats that these creatures are specifically designed to live in means they could never recover – risking the extinction of unique species. The physical recovery of the nodules that mining companies want to extract takes millions of years, and we do not know if creatures dependent on nodules can recover after their removal.

Reason 3: Disturbing one of our best allies against climate change

The deep sea is an incredibly important store of ‘blue carbon’, the carbon that is naturally absorbed by marine life, and which remains stored in deep sea sediment for thousands of years after these creatures die – helping to slow climate change.

Hydrothermal vents at Dom João De Castro. They are unusually shallow and support unique communities of organisms, often with special properties which interest both scientists and industry. UAC is conducting research here. The area has been designated a Natura 2000 site. Greenpeace is in the Azores with a team of scientists to survey and document deep sea life.

But by impacting on natural processes that store carbon, deep sea mining could even make climate change worse. The disruption caused by the machines may release carbon stored in deep sea sediments, and the wider impacts could disrupt the processes that store carbon in those sediments.

We know that we are facing a climate emergency. Why would we make it worse for ourselves?!

Reason 4: Impacting the ocean food chain

This widespread disruption to marine life would impact the whole ocean food chain. A Greenpeace investigation revealed that companies hoping to be involved in the supply chain are fully aware of this risk – a document circulated at a deep sea mining stakeholder meeting acknowledges “the potential extinction of unique species which form the first rung of the food chain.”

A shoal of Almoco Jacks on the Dom João de Castro seamount, Azores. These jacks travel far and wide across the open ocean, and this shallow volcanic caldera, just between Terceira and São Miguel islands, serves as a handy feeding point for them. Greenpeace is in the Azores with a team of scientists to survey and document deep sea life.

Reason 5: Do we want to destroy wonders that we are yet to discover and properly understand?

So far, we’ve only explored 0.0001% of the deep seafloor to see what lives there. We have so much more to learn about the deep ocean’s wildlife and ecosystems. How can companies properly risk manage something that we are yet to fully understand? There could be many more risks than they are aware of, from opening a new industrial frontier in the largest ecosystem on Earth. Without proper protection of the deep sea, we could destroy species and ecosystems yet to even be discovered.

Scyphozoan Jellyfish.

A selection of deep sea creatures that are found in the Arctic. The animals were documented by marine biologist, explorer and underwater photographer Alexander Semenov, head of the divers’ team at Moscow State University’s White Sea biological station.

No minerals or metals are worth destroying ecosystems we don’t even understand yet. Companies that use these materials for smartphones and renewable energy should be investing in recycling and new technology instead of threatening marine life for profit.

It’s clear that deep sea mining would be very bad news for our oceans. And the corporations that want to get going with this destructive practice know the risks. Just as the oil industry spent years downplaying the environmental risks of their product while convincing politicians it was essential for the economy, so now deep sea mining companies are trying to convince politicians they offer a “green solution”. This isn’t true.

Let’s not repeat our mistakes and let this risky industry get a grip on our deep seas. With the nature and climate crises that we are facing, the stakes are simply too high. We shouldn’t be asking ‘how much new harm will we allow?’ – we should be making ambitious plans to help our oceans recover to health.

To help make this happen we are building an unstoppable global movement for healthy oceans, to protect nature and tackle climate change. So far over 900,000 people globally have signed our petition, calling on governments to agree a Global Ocean Treaty next year, which can put vast areas off-limits to exploitation and raise environmental standards for any industrial activity in international waters, putting protection at the heart of how we collectively manage our global oceans. A strong Global Ocean Treaty can help protect the hidden treasures of the deep sea from reckless exploitation.

The deep sea is the largest ecosystem on Earth. We should protect it and learn from it, not mine it. Join the movement and sign the petition for a strong Global Ocean Treaty.

This blog was originally published on Greenpeace International’s website.

The seas provide half of our oxygen, food for a billion people, and a home for some of the most spectacular wildlife on Earth. But the impacts of climate change, pollution and destructive industries mean they’re in more danger than ever.

Take action

Discussion

Deep Sea Mining is an invasion to territories that do not belong to us BUT to its inhabitants. Their resources are part of their life.