If you’ve been following global climate and finance politics lately, you’ll have noticed a strange contradiction.

On the one hand, governments keep telling us we need more climate finance, fairer taxation, and new public resources to deal with climate breakdown, inequality and crumbling public services. On the other hand, when it comes to the one global forum designed to actually fix international tax rules – the UN Tax Convention – that bold ambition doesn’t translate.

These negotiations, currently underway in New York, present a unique chance to hold corporate tax avoiders and polluters accountable, unlocking trillions in public funds for climate action, nature protection, and vital public services. Instead of rising to that moment, however, the process risks failing to deliver the transformative change many countries are calling for.

Same governments. Same problems. Very different energy. So what’s going on?

Principles everywhere, commitments nowhere

The latest draft of the UN Tax Convention includes articles on sustainable development and taxing high-net-worth individuals (HNWI). That’s good news. A few years ago, neither would even have made it into the room.

But here’s the catch: they’re still written mostly as ‘principles’, not commitments.

The sustainable development article remains declaratory. It acknowledges that tax cooperation should support social, economic and environmental goals, without spelling out how, or what kinds of mechanisms would be needed to deliver them. No change to this article since the Terms of Reference were set out.

The article on high-net-worth individuals has improved on paper (it uses ‘shall’ instead of ‘agree’ now), but still stops short of what’s actually needed to tax extreme wealth effectively and fairly.

In short: governments agree that something should happen, but appear reluctant when it comes to the details of how to actually make it happen. That’s like agreeing to catch smugglers, but banning customs from opening the luggage.

The paradox no one wants to name

This is where things get awkward.

In other international forums (COP30, G20, FfD4 to name a few examples), many of the same governments are already making much bolder statements. For example:

- Calling for progressive environmental taxation,

- Demanding new climate finance sources,

- Warning about the social and political risks of inequality,

- and even (occasionally) saying the words ‘tax extreme wealth’ out loud.

In 2025, at the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4) in Seville, Spain, governments committed to improving tax cooperation and transparency, explicitly referencing progressive taxation to fund social protection and integrate undeclared wealth, and in written submissions, countries such as Brazil, Colombia, Germany, France, Spain and Sierra Leone have explicitly supported stronger cooperation on HNWI taxation in the UN process. Many African countries, including Zambia and Nigeria, have repeatedly highlighted in their plenary interventions how our broken global tax system undermines development and climate action.

Since the UN Tax Convention negotiations began in 2025, at least 17 countries have made supportive statements for more detail to be added on the issue of sustainable development, several of whom have explicitly endorsed inclusion of environmental taxation and the polluter pays principle.

And yet, when negotiations move from statements to drafting, ambition narrows. Not all elements raised in countries’ submissions find their way into the Chair’s text, and several governments continue to defer to high-level, non-committal language. Political choices are reframed as technical questions by some countries, while the potential of the Convention to support climate action and sustainable development through tax policy remains underexplored. Issues with clear distributional complexities are quietly treated as beyond the Convention’s scope.

Sovereignty: the most misused word in the room

Whenever ambition stalls, one word inevitably appears: sovereignty.

We’re told that taxing the super-rich is a domestic issue. That coordinated standards on taxing polluters would infringe national autonomy. That global rules somehow threaten democratic choice.

But here’s the inconvenient truth: there is nothing sovereign about a tax system you can’t enforce.

Here’s the problem: in today’s world, money, profits, and assets move faster than national laws, often through loopholes and tax havens, and across borders, while information about these assets does not. Countries trying to take action alone end up competing with each other, lowering standards, and losing billions in the process. These are funds that could have supported climate finance and sustainable development.

Real sovereignty isn’t the right to say “no” alone. It’s the ability to withstand pressure together to enforce rules that protect public resources and the planet. This is why we need global tax reform.

Why the UN Tax Convention matters more than ever

We’re living through a rupture, not a transition.

The old era of club-based tax governance (dominated by a handful of rich OECD countries) is cracking under its own contradictions. At the same time, multilateralism itself is under attack, with institutional deadlock and unilateral action increasingly replacing cooperation, from the UN Security Council to climate negotiations.

That’s precisely why the UN Tax Convention matters. It’s the only forum in international tax governance where every country has a seat, decisions aren’t hostage to unanimity, and tax cooperation can be anchored in sustainable development, not just capital mobility.

In short: it’s the one place where we can move from fair taxation by permission to fair taxation by right.

Hey reader, if you’ve reached this point it means this is a topic you’re really interested in, and we would like to know who you are, so please leave a comment below and share your thoughts!

What needs to change

If the Convention is to live up to its mandate, four things need to happen:

- Moving beyond “exploring” coordination. On taxing extreme wealth, governments need to commit to developing coordinated approaches including minimum standards, progressive elements and redistributive options, not just endlessly discussing them.

- Naming the preconditions. You can’t tax what you can’t see. That means committing to transparency tools like beneficial ownership information, asset registries and effective exchange of information, especially for high-net-worth individuals. It means fair taxing rights based on economic activity. It means true sovereignty.

- Agreeing new rules to tax polluters. That starts with a new global agreement that countries will deliver – nationally and internationally – progressive environmental taxation in line with the polluter pays principle and the principle of equity (common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities). From there, new mechanisms can be established, like a global tax on the profits of fossil fuel companies to boost international climate finance.

- Embedding the articles in the bigger goal. Taxing the super-rich and corporate polluters aren’t side issues. They are central to funding climate action, protecting nature and rebuilding trust in public institutions. The Convention should say so, clearly.

The moment we stop pretending

The tools exist. The political arguments are already being made elsewhere. And the costs of inaction are painfully visible.

What’s missing isn’t expertise – it’s alignment.

If governments are serious about climate justice, social cohesion and sustainable development, the UN Tax Convention is not the place to be cautious. It’s the place to be honest.

Because in a world where crises are global and wealth is mobile, collective action isn’t a loss of sovereignty – it’s the only way to reclaim it.

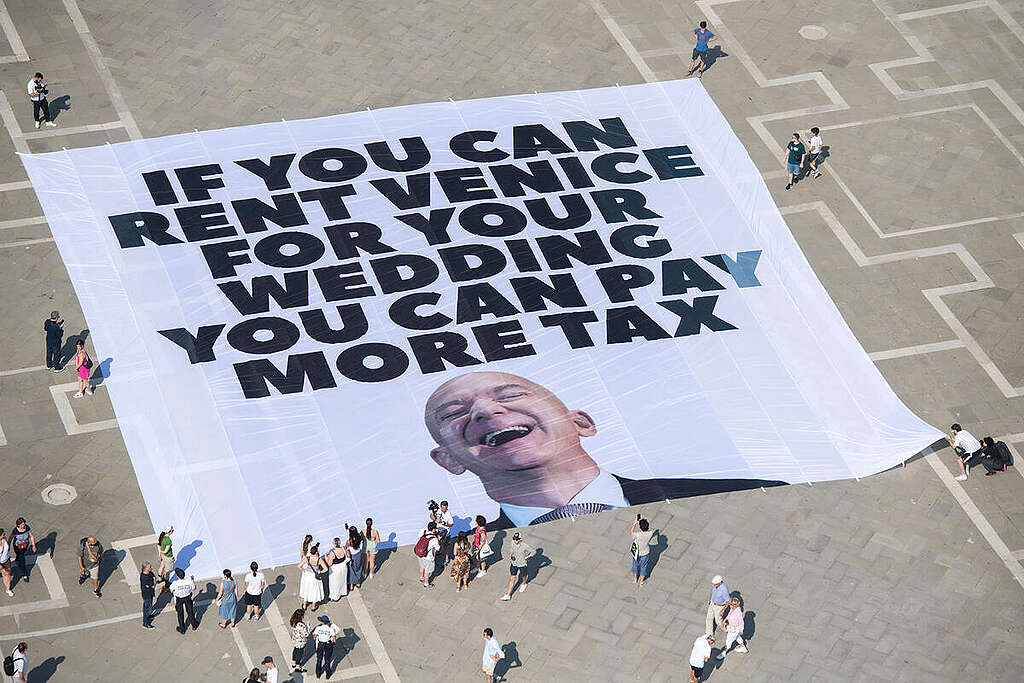

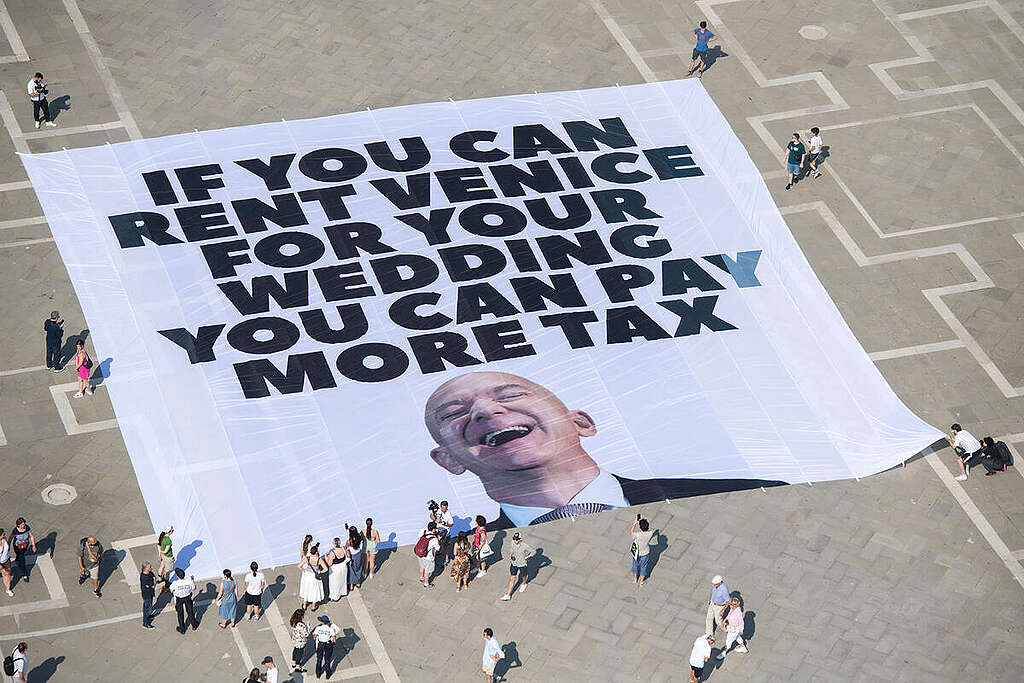

And yes, taxing the super-rich and corporate polluters is part of that story.

Together, let’s urge governments to tax the super-rich and fund a green and fair future.

Add your nameClara Thompson is the Global Tax Justice Lead at Greenpeace International. She is currently in New York City for the 4th round of negotiations of the United Nations Treaty on International Tax Cooperation (also known as the UN Tax Convention).