Part 1: In what ways does the EQ (Amendment) Act 2023 fall short?

It may not be obvious, but a significant aspect of striving to enhance Malaysia’s environmental quality is closely tied to the numerous minor regulatory barriers that impede our pursuit of a clean, healthy, and sustainable future.

Some may perceive having a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment as a privilege, when it should be plainly understood as a fundamental human right of every Anak Malaysia to well-being.

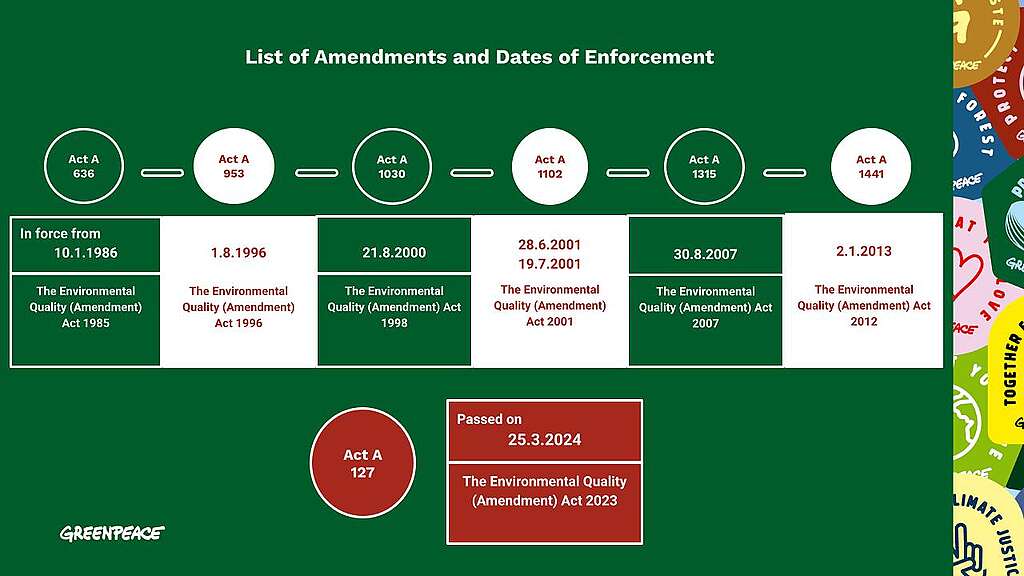

On March 25th, 2024, Parliament passed the Environmental Quality (Amendment) Act 2023, marking their seventh effort to rectify the inherent flaws within the venerable Environmental Quality Act (EQA) initially enacted in 1974. In other words, this milestone signifies that the EQA 1974 has now reached the momentous age of half a century of, safeguarding the quality of our environment.

The highlights of the EQ (Amendment) Act 2023 focus on three long-overdue issues. These include a more established open burning provision, empowerment of both the Director General and the Minister, as well as stricter penalties across 25 sections to ensure better enforcement and compliance.

In particular, the open burning provision establishes a definition and enhances penalties to tackle environmental issues and decrease air pollution. Empowering both the Director General and the Minister will streamline decision-making processes and improve effectiveness in environmental governance. Moreover, the stricter penalties aim to deter violations and foster a culture of accountability towards environmental protection. Table 1 is a summary of the amendments:

Table 1: A Summary of the EQ (Amendment) Act 2023

| Part | Amendment | Section |

| I – Preliminary | Add the definition of “open burning” to the existing list of 43 environmental-related terminologies. | 2 |

| II – Administration | Empower the Director General to determine uniforms for officers appointed under the respective subsection. | 3 |

| III – Licences | Increase the penalties for offences under the respective section and establish minimum and maximum fines. | 16 |

| IV – Prohibition and Control of Pollution | Increase the penalties for offences under the respective sections and establish minimum and maximum fines.Insert the offence and penalty provisions for contravening the respective subsection.Consolidate two respective sections to strengthen the provisions relating to open burning. The amendment also aims to increase the penalties and to provide for minimum and maximum fines. | 18, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 29, 30A, 31, 31A, 33, 34A, and 34AA. 19, 32 29A and 29AA |

| IVA – Control of Scheduled Wastes | Increase the penalties for offences under the respective section and establish minimum and maximum fines. | 34B |

| VI – Miscellaneous | Increase the penalties for offences under the respective sections and establish minimum and maximum fines.(1) All compounds must first obtain written consent from the Public Prosecutor before being issued.(2) Increase the total amount of the compound from a maximum of 2,000 ringgit to a sum not exceeding 50% of the maximum fine allocated for each offence.Empower the Minister to make regulations prescribing compoundable offences, increasing the term of imprisonment from two years to five years, and providing penalties for continuing offences. | 37, 41, 48, 48A and 48AD 45 51 |

This raises the question: “Is the EQ (Amendment) Act of 2023 sufficient to safeguard the quality of our environment?”

Tremendous progress has indeed been made in the last 50 years since the introduction of EQA 1974. However, despite undergoing rigorous evaluation and numerous revisions, there still exists a prevalent inclination towards adopting a prevention and mitigation stance. This approach overlooks the necessity for a comprehensive act that encompasses not only prevention and mitigation but also adaptation, protection, and restoration measures to address pressing anthropogenic environmental crises and climate change challenges.

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is a preventive tool. Researchers Sani and Kamaruddin have emphasised the prominence of the EQ (Prescribed Activities) Order 1987, which facilitated the lawful execution of EIA procedures, representing a crucial progression in the EQA 1974. They stated that it heralded a transformative era and methodology, indicating a transition from a “curative” to a “preventive” stance (Sani & Kamaruddin 2016). This shift underscores the country’s proactive commitment towards environmental preservation.

The successful rally of the Malaysian coral reef community against the construction of a proposed new international airport in Tioman Island is a prime example. After carefully examining the EIA report, Reef Check Malaysia (RCM) was able to discern potential environmental hazards associated with the project. RCM then collaborated with other stakeholders to prevent an impending ecological catastrophe.

The details of the skewed EIA report by Asia Pacific Environmental Consultants Sdn Bhd were publicly disclosed, allowing for public scrutiny and challenging its bias towards its financiers, the developers Tioman Infra Sdn Bhd. This instance also revealed certain shortcomings in terms of enforceability, impartiality, transparency, and public participation within the EIA procedures.

Another preventive tool is penalty. Taking a closer look at the Kim Kim River Case, the Sessions Court’s last December ruling, which levied a fine of RM100,000 on the lorry driver guilty of illicit waste disposal into the Kim Kim River and a RM320,000 penalty on P Tech Resources Sdn Bhd, has been deemed insufficient by numerous parties. This has led to demand for more severe punishments. In response to this outcry, the state government has resolved to petition the Deputy Public Prosecutor (DPP) for an elevation in the maximum penalty to RM100,000 per offence.

To me, the maximum penalty is a gross mismatch to the deep-seated suffering that either the environment or victims endure. It also blatantly disregards the broader societal repercussions, which manifest as financial losses borne by individuals and government institutions alike.

The United States, for instance, has implemented extensive environmental laws such as the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). This legislation ensures that parties responsible for environmental damage are held accountable for remediation expenses and liabilities. This serves as an exemplary illustration of how we can safeguard our environment while simultaneously promoting fairness and justice within society.

The Basel Action Network (BAN) has recently discovered that Malaysia is increasingly becoming the preferred destination for unlawful e-waste traders from the United States and Canada, particularly concerning plastic waste. This instance of slow-violence resulting from waste colonialism is disconcerting.

Last month alone, two cases occurred. The Malaysian Immigration Department conducted an operation near Port Klang. They seized approximately RM 496, 020 (USD 105, 000) in cash and arrested 48 individuals from an e-waste dismantling facility, including board members and the director. On March 21st, another raid took place in Petaling Jaya where officials uncovered an e-waste dismantling facility hidden within an oil palm estate, spanning an area roughly equivalent to five football fields.

In 1993, Malaysia officially became a party to the Basel Convention. For many years, the European Union (along with other Global North countries) has been exporting plastic waste to developing nations. Initially, plastic waste was not covered by the Convention since it did not fit into the categories of hazardous or other controlled wastes. To rectify this omission, an amendment was proposed by Norway and subsequently adopted in 2019, commonly known as the “Norwegian Amendment“. As per January 2021, it has been put into effect to regulate international trade involving mixed and contaminated plastic wastes (Annex II, Y48).

The Norwegian Amendment specifically addresses plastic waste that contains fluorinated polymer, such as those found in electrical wiring, cable insulation, and pipe linings. Previously, these materials were classified as ‘clean’ plastic – a category not regulated by the Convention. This encompasses the casings for a significant majority of electronic devices. Consequently, importing countries would be required to provide consent prior to the shipment of any exports containing fluorinated polymer plastic waste. The ultimate aim of this amendment is to halt the influx of plastic waste into developing African and Asian nations in order to mitigate harmful pollution affecting local inhabitants and their environment.

It is indeed commendable that Section 34B, the clause governing the transboundary movement of scheduled wastes, has witnessed an increase in penalties under the EQ (Amendment) 2023.

I firmly believe that classifying ‘plastic’ as a waste category in accordance with Section 2 of the EQA 1974 and the First Schedule of the EQ (Scheduled Wastes) Regulations of 2005 holds substantial importance. Yet, it is currently lacking. There is a need to modernise the terminologies listed in Section 2 to ensure they are congruent with contemporary international standards.

One might question why approaches like adaptation, protection, and restoration are essential in addressing the environmental crisis triggered by human activities and in combating climate change.

Mitigation strategies are undeniably key to minimising damage, halting ongoing effects, and reducing future implications. However, some communities are already experiencing the devastating impacts of these environmental catastrophes. Hence, it’s equally vital that we implement measures to avert further disasters, bolster resilience, and diminish vulnerability – an approach commonly referred to as adaptation.