Following his piece on the late Pope Francis, Jefferson Chua continues his reflections on the relationship between the Papacy of the Roman Catholic Church and climate change, now in the hands of a new pontiff.

There is a photo of Robert Francis Prevost, back then when he was still archbishop in Chiclayo, Peru, wading through the floodwater that devastated his parish during the historic 2017 El Niño floods. He struck a calm figure who had little to no qualms about being in the middle of a disaster. The photo made me think: what does Prevost, now Pope Leo XIV, think of climate change, and–more importantly– the solutions needed to address it?

There are quite a number of clues as to what he would have thought about climate change. He largely aligns with the late Pope Francis’s pivot towards the environment and the Laudato Si agenda, in urging the church to transform words into action in addressing the climate crisis. He has likewise called for a “non-tyrannical relationship” with nature as a key ingredient in climate action, while warning of serious consequences brought about by technological innovation if it is not grounded in a reciprocal relationship with nature.

In the same breath he also mentions the Vatican’s recent adoption of solar power as well as the purchase of electric vehicles as positive steps in addressing climate change. In his younger years he has also pushed for petitions and shared opinions that seem to align with more urgent climate action and international cooperation.

I am drawn to the pope’s choice of name. His nominal predecessor, Leo XIII, stands among the giants of the petrine ministry because he took on arguably the greatest challenge of the church during his time: its relationship with the modern world. His encyclical, Rerum Novarum, not only articulated the church’s positionality in the modernizing and industrializing world, but also spoke about the dangers of unchecked capitalism and its impacts on rights, especially that of workers and laborers. In other words, Leo XIII signalled a critical gaze on unchecked profiteering and how this pursuit of more growth and wealth comes at the expense of the rights of those that were instrumental in achieving that wealth.

I wonder if Leo XIV will be able to transpose this critical gaze onto arguably the greatest challenge of our time, the climate crisis. Our era is characterized by the near-total domination of the corporate few who have reaped in record profits at the expense of everyone. Climate impacts have been increasing in intensity and regularity more than ever, resulting in staggering global losses. In 2024 alone, estimates vary from insurance payouts worth USD 137 billion, to upwards of USD 229 billion with just the ten costliest disasters of last year.

In contrast, just the five largest investor-owned oil and gas companies–Shell, Exxon Mobil, British Petroleum, Chevron, and Total Energies–earned USD 102 billion in 2024. The figure becomes even more mind-boggling if one looks at their profits in the last decade, which amounted to almost USD 800 billion. This greed is underlined by their business practices, with all of them announcing in different manners of speaking that they will not be phasing out oil and gas and will be cutting investments in green and renewable energy, while at the same time spending astronomical amounts of money to run advertising and marketing campaigns that paint a rosy picture of their supposed concern for the environment and climate action.

Taking a broader view lays bare this gross inequality: the world’s wealthiest 10% has caused two-thirds of global warming since 1990, which boils down to not just individual lifestyle choices, but more importantly to the concentration of wealth held by a very few but powerful group of people.

It is amid this sad and alarming backdrop that we find Leo XIV, who inherits a church in a world that is increasingly more difficult to live in, especially by those at the frontlines of the climate crisis. It is this world that also beckons on Leo XIV to transform the church “from words to action.” Climate action must go beyond platitudes and pursue accountability.

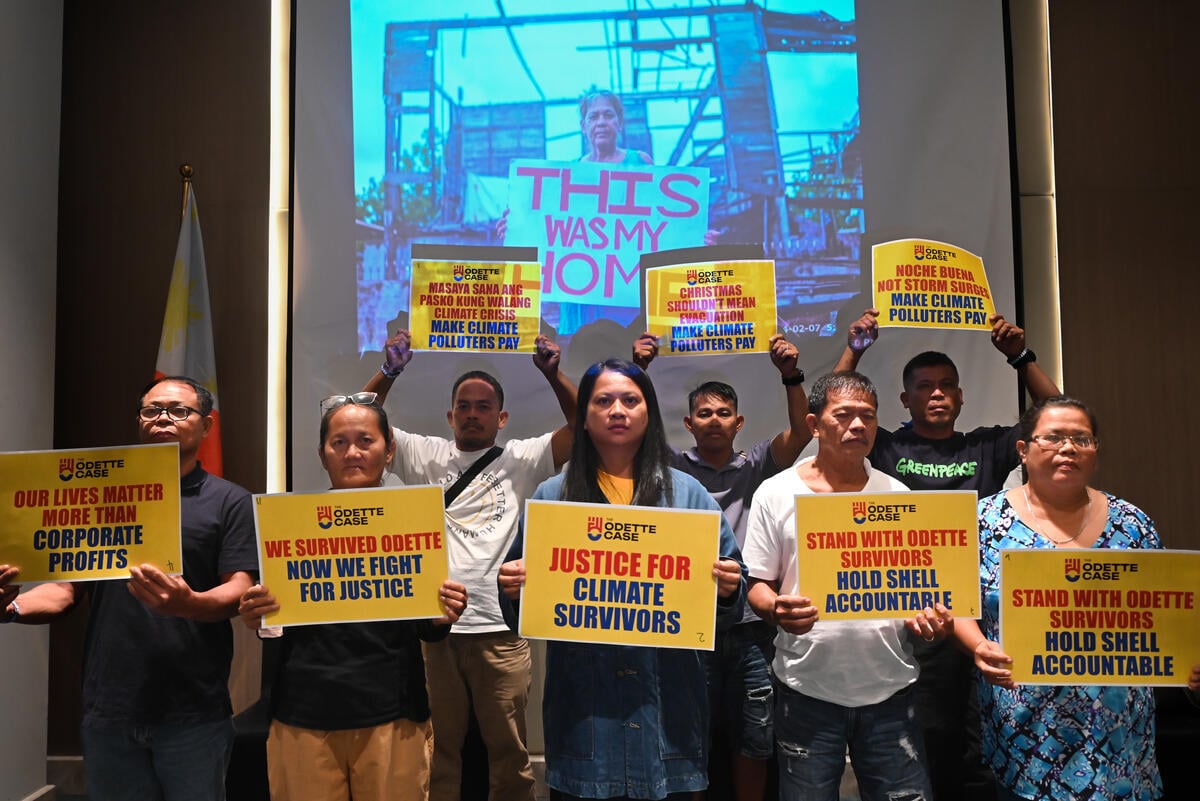

There are hopeful signals within the church. A good example would be the Philippines, which constantly ranks as among the most vulnerable countries to climate impacts. For instance, the Roman Catholic Church in the country has set 2025 as the target year when it will be fully divesting from coal and fossil gas investments. Religious-run academic institutions such as Mapua University has likewise pronounced that it too will be divesting from fossil fuels. Church-based grassroots communities and priests have likewise supported environmental defenders and indigenous groups against unchecked transition mineral mining, and have called for holistic climate accountability policies such as the CLIMA Bill. That there is a wealth of examples in the frontiers of the climate crisis should push Leo XIV to take on the fight for climate justice beyond discursive urging. He inherits a church that is suffering precisely because it is in the frontlines. In this manner, Leo XIV himself, through the office entrusted to him, also inherits this moral responsibility to act.

Perhaps none can encapsulate this moral imperative of his papacy better than an example from his adopted home, Peru. Saul Luciano Lliuya, a farmer from Huaraz, Peru, filed a case against German energy company RWE AG. Initially filed in 2015, Lliuya contested that RWE’s emissions–which is considered one of the biggest emitters in Europe–had a direct impact on the climate that is threatening the claimant’s home. After a successful appeal process in 2017 and initial hearings in March 2025, the court will issue an announcement this May. Lliuya’s case takes on and represents an increasingly-familiar experience by climate-impacted frontline communities of no accountability and increasing impacts.

One can imagine Leo XIV, in his white cassock, bearing witness to the increasing frequency of floods that Lliuya and countless others are experiencing and, perhaps, likewise add his influential voice to the growing chorus of those calling for accountability. If he is true to his name, and if his papacy signals an unbroken line from Francis’s concerns in Laudato Si, then there is no other alternative to calling out those who are most responsible for the climate crisis: not just individuals, not just countries, but corporations that have accumulated so much wealth while the least of us suffer the worst consequences of a common home in crisis.

Jefferson Chua is a Greenpeace Campaigner working on climate, based in the Philippines.

You might want to check out Greenpeace Philippines’ petition called Courage for Climate, a drive in support of real policy and legal solutions in the pursuit of climate justice.

The climate crisis may seem hopeless, but now is the time for courage, not despair. Join Filipino communities taking bold action for our planet.

Make an Act of Courage Today!