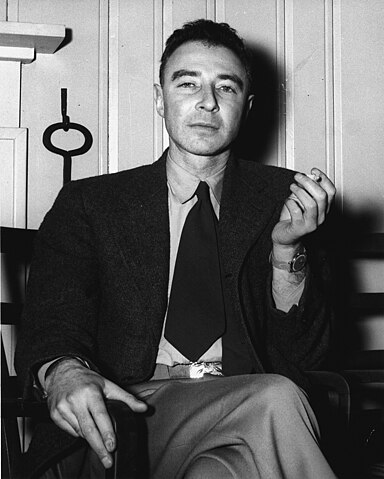

J. Robert Oppenheimer – the great nuclear physicist, “father of the atomic bomb”, and now subject of a blockbuster biopic – always despaired about the nuclear arms race triggered by his creation.

So the approaching 78th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing invites us to ask how far we’ve come – or haven’t come – since his death in 1967.

The Cold War represented all that Oppenheimer had feared. But at its end, then-US president George H.W. Bush spoke of a “peace dividend” that would see money saved from reduced defence budgets transferred into more socially productive enterprises.

Long-term benefits and rises in gross domestic product could have been substantial, according to modelling by the International Monetary Fund, especially for developing nations. Given the cost of global sustainable development – currently estimated at US$5 trillion to $7 trillion annually – this made perfect sense.

Unfortunately, that peace dividend is disappearing. The world is now spending at least $2.2 trillion annually on weapons and defence. Estimates are far from perfectly accurate, but it appears overall defence spending increased by 3.7% in real terms in 2022.

The US alone spent $877 billion on defence in 2022 – 39% of the world total. With Russia ($86.4 billion) and China ($292 billion), the top three spenders account for 56% of global defence spending.

Military expenditure in Europe saw its steepest annual increase in at least 30 years. NATO countries and partners are all accelerating towards, or are already past, the 2% of GDP military spending target. The global arms bazaar is busier than ever.

Aside from the opportunity cost represented by these alarming figures, weak international law in crucial areas means current military spending is largely immune to effective regulation.

The new nuclear arms race

Although the world’s nuclear powers agree “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought”, there are still about 12,500 nuclear warheads on the planet. This number is growing, and the power of those bombs is infinitely greater than the ones dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

According to the United Nations’ disarmament chief, the risk of nuclear war is greater than at any time since the end of the Cold War. The nine nuclear-armed states (Britain, France, India, Pakistan, North Korea and Israel, as well as the big three) all appear to be modernising their arsenals. Several deployed new nuclear-armed or nuclear-capable weapons systems in 2022.

The US is upgrading its “triad” of ground, air and submarine launched nukes, while Russia is reportedly working on submarine delivery of “doomsday” nuclear torpedoes capable of causing destructive tidal waves.

While Russia and the US possess about 90% of the world’s nuclear weapons, other countries are expanding quickly. China’s arsenal is projected to grow from 410 warheads in 2023 to maybe 1,000 by the end of this decade.

Only Russia and the US were subject to bilateral controls over the buildup of such weapons, but Russian president Vladimir Putin suspended the arrangement. Beyond the promise of non-proliferation, the other nuclear-armed countries are not subject to any other international controls, including relatively simple measures to prevent accidental nuclear war.

Other nations – those with hostile, belligerent and nuclear-armed neighbours showing no signs of disarming – must increasingly wonder why they should continue to show restraint and not develop their own nuclear deterrent capacities.

The threat of autonomous weaponry

Meanwhile, other potential military threats are also emerging – arguably with even less scrutiny or regulation than the world’s nuclear arsenals. In particular, artificial intelligence (AI) is sounding alarm bells.

AI is not without its benefits, but it also presents many risks when applied to weapons systems. There have been numerous warnings from developers about the unforeseeable consequences and potential existential threat posed by true digital intelligence. As the Centre for AI Safety put it:

“Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.“

More than 90 countries have called for a legally binding instrument to regulate AI technology, a position supported by the UN Secretary General, the International Committee of the Red Cross and many non-governmental organisations.

But despite at least a decade of negotiation and expert input, a treaty governing the development of “lethal autonomous weapons systems” remains elusive.

Plagues and pathogens

Similarly, there is a fundamental lack of regulation governing the growing number of laboratories capable of holding or making (accidentally or intentionally) harmful or fatal biological materials.

There are 51 known biosafety level-4 (BSL-4) labs in 27 countries – double the number that existed a decade ago. Another 18 BSL-4 labs are due to open in the next few years.

While these labs, and those at the next level down, generally maintain high safety standards, there is no mandatory obligation that they meet international standards or allow routine compliance inspections.

Finally, there are fears the World Health Organization’s new pandemic preparedness treaty, based on lessons from the COVID-19 disaster, is being watered down.

As with every potential future threat, it seems, international law and regulation are left scrambling to catch up with the march of technology – to govern what Oppenheimer called “the relations between science and common sense”.

Take action for environmental protection. Please make a donation today. Greenpeace exists because this fragile earth deserves a voice. It needs solutions. It needs change. It needs action.

DonateAlexander Gillespie, Professor of Law, University of Waikato.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This article is a guest post and doesn’t necessarily represent the views of Greenpeace.