On what has turned out to be a muggy and cloudy spring day, I’ve driven past the northern shore of Lake Rotorua to arrive at the Te Puea orchard. A basic shed greets me and it’s ghostly quiet. It turns out, the action is at the back – behind the nursery and veggie patches, about 60 hands and feet are busy planting.

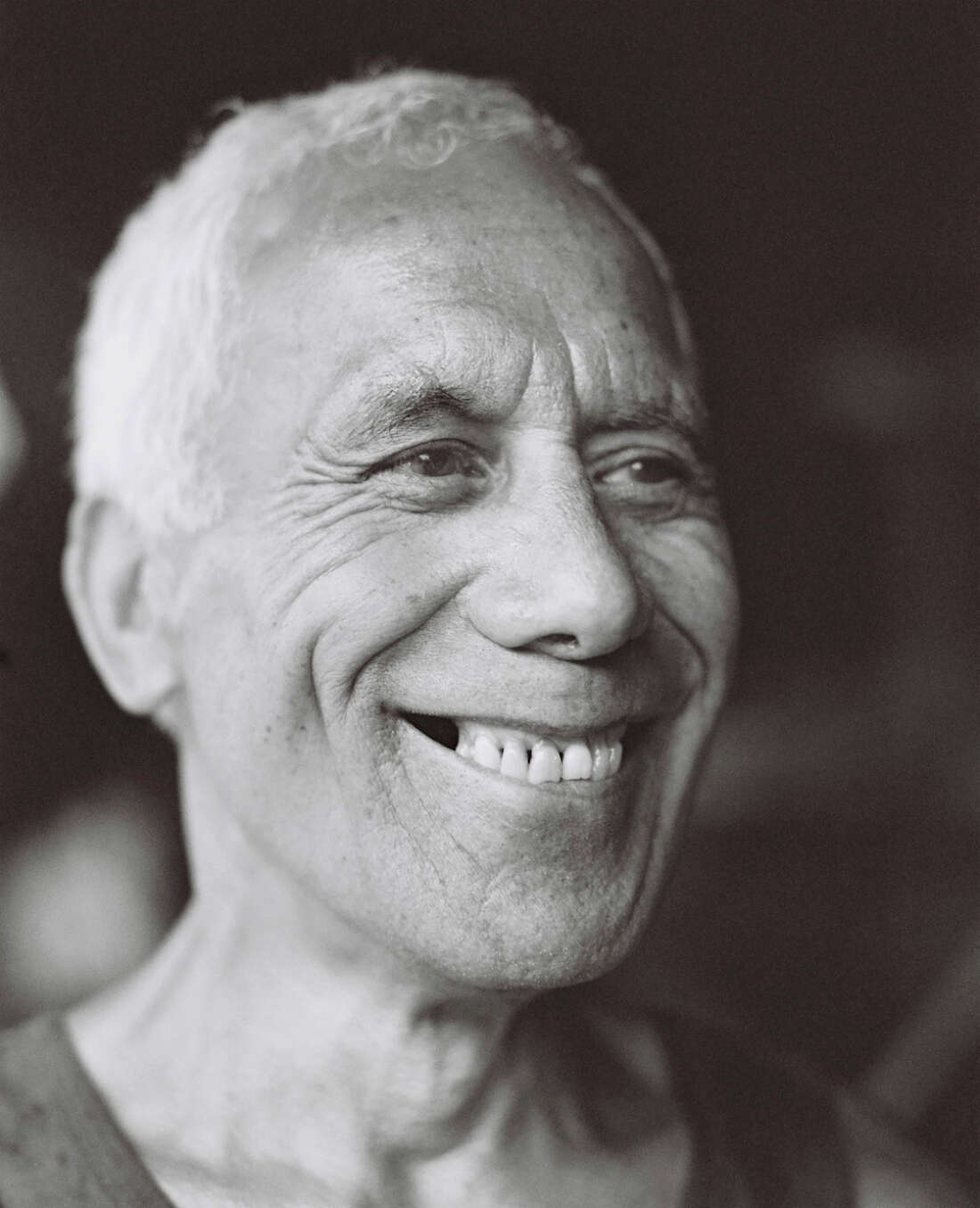

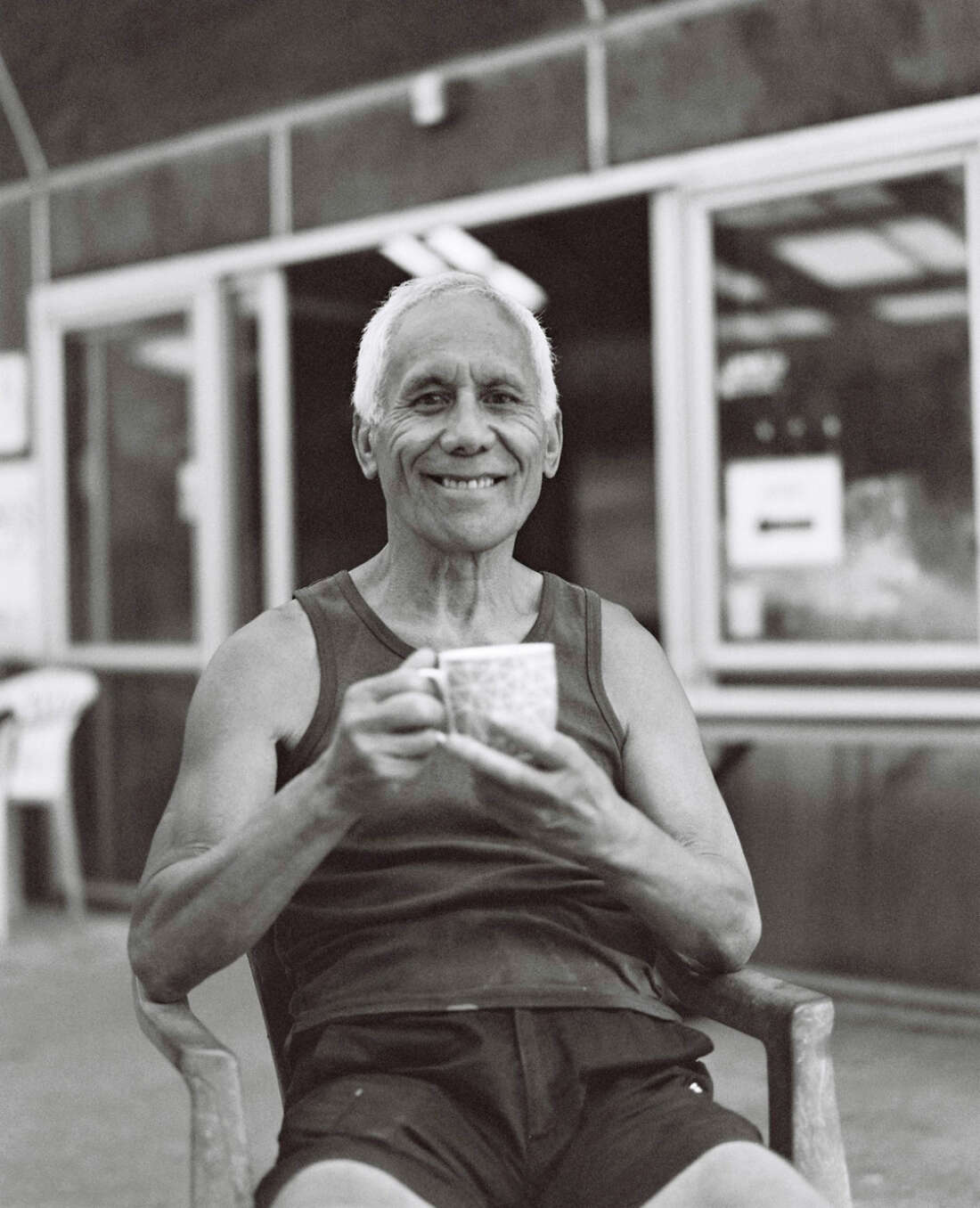

The field is full of school kids and korua, including 72-year-old Te Rangikaheke Kiripatea who’s giving out instructions. His dog Nala watches from his truck parked near the raised rows that await tipu- shoots.

Te Rangikaheke smiles at the scene and tells me, “our old people had an intimate relationship with their atua (gods) and their environment. They walked and talked with their atua on a daily basis and connected to their environment through the maramataka, the lunar calendar.” It happens that the moon is in the maure phase today- a good time to be planting and fishing. A day like this bears with it the potential that kai will be plentiful and the kūmara will be large. Today is annual kūmara planting day.

Te Rangikaheke runs Kai Rotorua along with co-founder Jasmine Jackson. The volunteer-driven body comprises over 130 individuals and organisations. “Volunteers come and go, some with and some without an agenda” says Te Rangikaheke, “But our volunteers know their strengths and apply themselves accordingly. Whether it is easy or hard is not a scale of measure we use.”

The tone for today was set at the initial planting where Te Rangikaheke recited an oriori, a Māori lullaby. “It’s the oriori as our korua and kuia from Waikato Tainui planted the first of the tipu” says Te Rangikaheke.

The oriori was composed in the early 1800s by Enoka Te Pakaru from the Te Aitanga-a-Mahaki iwi, East Cape. The oriori is of pre-European origin and the kumara is referenced at line 7.

Pō! Pō!

E tangi ana Tama ki te kai māna!

Waiho me tiki ake ki te Pou-a-hao-kai,

Hei ā mai te pakake ki uta rā

Hei wai-ū mō Tama!

Kia mauria mai e tō tipuna, e Uenuku!

Whakarongo! Ko te kūmara ko Pari-nui-te-ra.

Ka hikimata te tapuae o Tangaroa,

Ka whaimata te tapuae o Tangaroa.

Tangaroa! Ka haruru!

My son is crying for food!

Wait until it is brought from the pillars-of-netted-seafood,

And the whale is driven to the shore

To give you milk, my son.

It will be given by your ancestor Uenuku.

Listen! The kumara is from the Great Cliffs of the Sun.

Tangaroa is striding there,

Tangaroa is striding there,

Tangaroa! Listen to the roar!

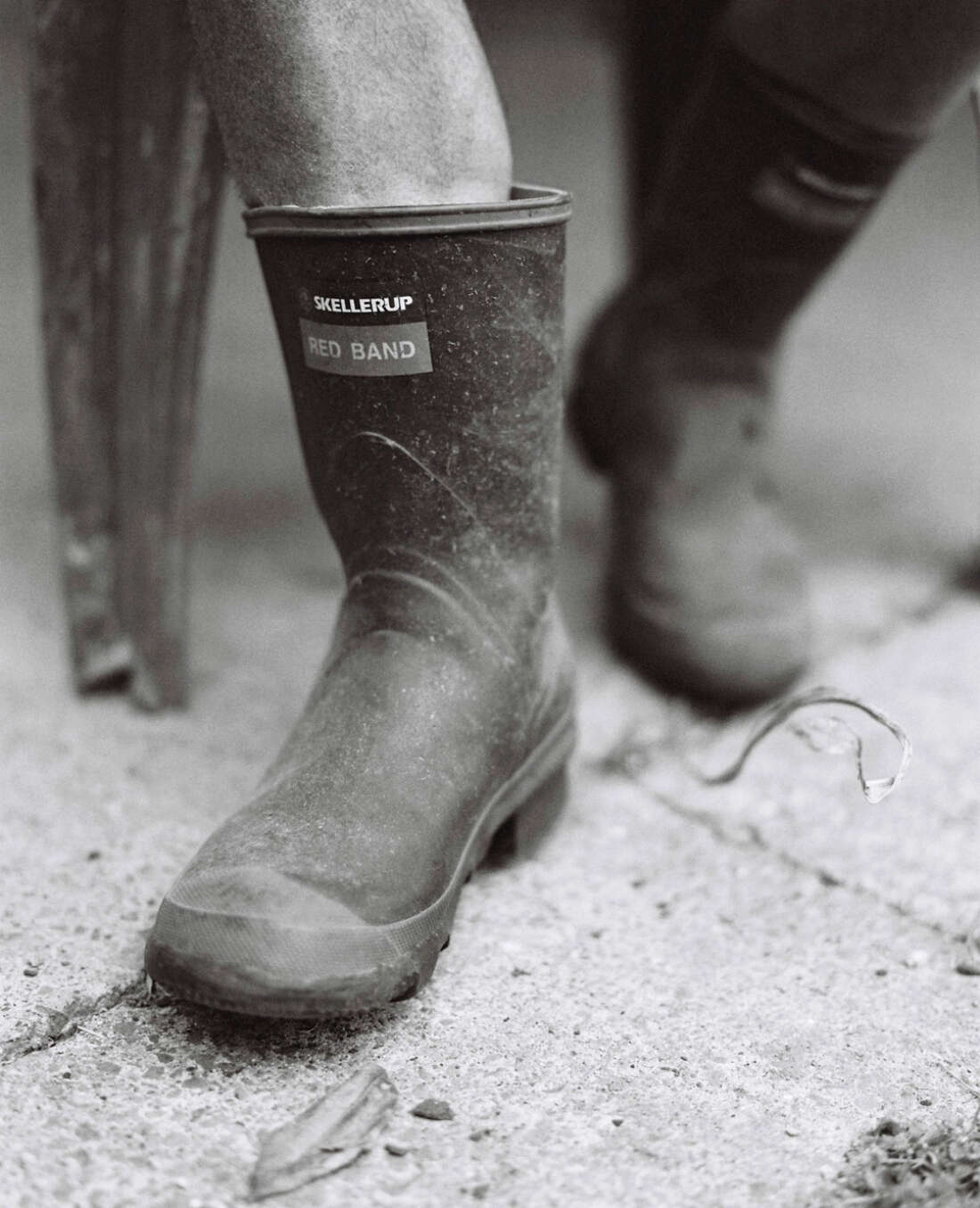

The soil here is dark, crumbly and light to the touch. Kūmara likes this sort of soil. Too dense and the kūmara tend to bury themselves too deeply. The tipu are usually planted in a ‘j’ shape, traditionally with the tip facing the direction of the rising sun.

This orchard is named after Princess Te Puea Herangi. Te Rangikaheke explains she was a formidable Māori leader, a wahine toa, mana wahine- a visionary from Waikato and Tainui iwi. Her mother, Tiahuia, was the elder sister of Kingi Mahuta, Māori royalty with Te Arawa whakapapa.

Princess Te Puea established a farming initiative in the area with help from Sir Apirana Ngata of Ngati Porou. Princess Te Puea was bent on raising the economic wellbeing of Tainui. Along with Sir Apirana, many whanau of Waikato Tainui and Ngati Porou were settled on the land blocks in the area.

“Our food chain is fucked and we need to do something about that. We do something about it by disrupting the status quo.”

Te Rangikaheke is really a community gardener at heart. His mission is to preserve the taonga of traditional kai and the vast variety of kūmara — “a kūmara bank” is what he likes to say is the vision. At 70, he is a man who minces no words. I ask him why he does what he does.“Our food chain is fucked and we need to do something about that.” he says. “We do something about it by disrupting the status quo.”

Reriata Makiha, a koroua from the Hokianga who is present and lending his maramataka advice to the group shows me how they had success planting tipu in a slightly different way. He demonstrates coiling the root of the sapling to form a coin-size loose circle, and talks to me about a huge harvest they had as a result in Northland last year.

There are a lot of knowledgeable korua here today, and they are all here for the same reason- to preserve and pass on traditional Maori food-growing wisdom. “By reconnecting whanau with Papatūānuku,” says Te Rangikaheke, “we want to ignite an interest in healthy kai as a means of connecting people to their heritage as well as the obvious health benefits. The quality of our food is seriously compromised with countless fast food outlets, processed food and food wrapped in plastic.”

Over the years Kai Rotorua have taken head-on the food security problem by building free veggie gardens in people’s backyards, teaching children and adults how to grow traditional and staple food crops. In particular they favour kūmara and karoro, moemoe and taewa riwai – Maori potato. They also worked with local scientists at Scion Institute to connect students with kai using 3D printing technology as the mechanism. By making virtual models of harvested kumara, students would learn to print them in 3D using corn-based plastics. The idea behind this was to get students to engage with science through their own culture, the history of the kumara voyage from ancestral Hawaiiki and to mātauranga.

The success of Kai Rotorua is evident across so many spheres. In its first year of operation Kai Rotorua produced over 500kg of 14 kūmara varieties. Many of these have cultural significance for Te Arawa as well as other iwi. Over 2000 tipu to date have been gifted to kura, volunteers and community groups. Additionally, over 250 students from six local schools have engaged in education sessions around growing kūmara.

This is a journey that began in July 2016 with 68 backyard gardens for whanau and kindergartens across Rotorua in the space of one week. It was a demonstration of how a community can galvanize itself and engage a group of passionate volunteers.“We began as the Rotorua Local Food Network,” explains Te Rangikaheke, “using a multi-pronged approach to address food security and food systems, a key component of which is focusing on traditional Maori food crops.”

The aim was to make healthy, locally grown food affordable and accessible, and for local farming to thrive. Simple really.

“Almost all of us eat out of supermarkets and cafes and put our trust in these businesses to provide us with good food,” explains Jasmine Jackson. “Many common food production methods in use today are not sustainable long term, and the food choices we make every day can help deliver the change needed”

Historically Maori were prolific gardeners. Every iwi had a māra kai (food garden). Maori tended their gardens on a daily basis and worked in unison to achieve outcomes in the growing of kai. The Māori connection to the kūmara is referenced and demonstrated throughout history. “Our purpose of reconnecting us to Papatūānuku is through kūmara.” says Te Rangikaheke. “It is difficult to connect Māori to a carrot and the kūmara is a hook to achieve our purpose. The kūmara appears in our kōrero, is present in our whakapapa, our pakiwaitara and is referred to in so many of our waiata tawhito. Our tribal narratives relating to the arrival of the kūmara from Hawaiiki here to Aotearoa vary from iwi to iwi, including its mythical whakapapa .“There is a wonderful celestial connection to the kūmara that is revealed through stories in our culture.It is said that Rongo-maui’s brothers scolded him for failing to feed his whanau so he ascended to the Heavens to ask his brother Whanui (celestial guardian of the kūmara) for kūmara to take back to his whanau,” continues Te Rangikaheke. “Whanui would not consent so Rongo-maui hid and secured some kūmara by stealth. Rongo-maui returned and gave the seed to his wife Pani-tinaku who gave birth to the kūmara at the sacred waters of Monariki.”

Covid-19 and its challenges continue to feature heavily in the kōrero I share with Te Rangikaheke long after I have left the orchards. “On the upside Covid-19 brought our whanau and our community to the realisation of questioning where our kai comes from, the importance of a resilient future and food security in particular.” says Te Rangikaheke. “During the lockdown there was a considerable increase in people beginning to grow their own vegetables. Here in Rotorua, 80 trucks a day deliver kai to supermarkets. That is a lot of diesel, so the question [is raised] of what happens when the diesel runs out? Supermarket shelves will be without food after 3 days and we experienced this on a smaller scale during lockdown,” he says.

The shores of Lake Rotorua, somewhere near historic Hamurana, seem a good spot for me to reflect on an inspirational time spent with a group of busy hands and big hearts planting kai today. In its essence, a post-Covid era provides us an opportunity to rethink and make paradigm shifts in our attitude to food,especially where it comes from. In Te Rangikaheke’s words, “food provenance will be the key to food security and we need, at a local and regional level, to teach more people to grow their own kai.”

First published on Stone Soup. Photography: Aaron McLean