Late last month on a bleak rainy day Jessica Desmond sat on a six metre long raft for over 10 hours, blocking a Talley’s bottom trawler from leaving Port Nelson. A former oceans campaigner at Greenpeace Aotearoa, Jess talks to us about why she put her body on the line to help stop bottom trawling on seamounts and why she wants the destructive fishing practice banned.

Can you tell me about the action in Nelson?

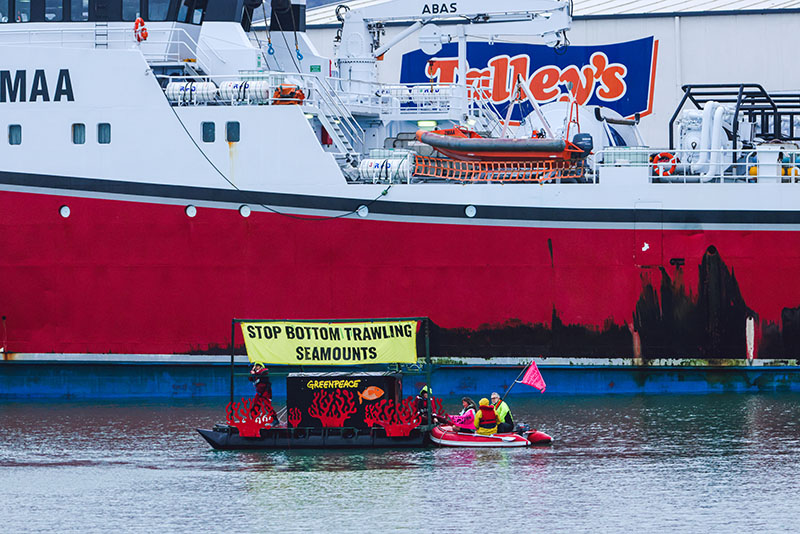

So my friend Christine Rose and I took a large raft out into the Nelson harbour and used it to essentially block one of Talley’s big factory trawlers from leaving the port. We wanted to disrupt their activities because they keep bottom trawling on seamounts – so we took direct, peaceful action.

What was the raft like?

It had big pontoons underneath that made it float and we had a deck with a small house structure that provided shelter – which was great because the weather was pretty bad all day. Above the shelter we had a large banner that said “Stop Bottom Trawling Seamounts” and the whole raft was covered in cutouts representing Gorgonian corals. They are really beautiful, slow growing corals that we know get wiped out by New Zealand bottom trawlers, so we wanted to use them as a representation of the destruction – of what’s at stake and what’s lost – when the bottom trawlers come and bulldoze these seamounts.

The Talley’s trawler looks huge compared to the raft. What was it like from your perspective?

It was sort of amazing in a really terrible way. I’ve been campaigning on bottom trawling for a long time but I’d never been so close to a trawler before and just seeing this scale of it. First of all the doors. They’re enormous: huge, hulking pieces of metal which they drop to open the nets. Imagining them being dragged along the seafloor is horrifying. I also couldn’t get over how big the ramp was. The bottom trawling nets get pulled up the ramp and I was trying to imagine the scale of it: the amount of fish and other marine life that gets hauled in. It really brought it home for me how destructive bottom trawling seamounts is – and the scale of what these trawlers can take from the ocean very quickly in this smash and grab sort of fashion.

What’s so special about seamounts?

Well if you imagine the seafloor as just like land, I mean it’s the same, just covered in water. It’s not flat, you have knolls and hills and rises, right up to mountains. Because seamounts rise off the seafloor they become hotspots for biodiversity. Corals and sponges and all sorts of weird and wacky creatures and colonies grow on these hills and mountains. Often, because they’ve been formed by geothermal activity, there’s all sorts of differences in the chemicals and the temperatures in the water so life that doesn’t exist anywhere else on the planet can flourish there.

“It really brought it home for me…the scale of what these trawlers can take from the ocean…in this smash and grab sort of fashion.”

Your whole face lights up talking about seamounts! So you’re saying many creatures calling seamounts home are unique?

Exactly. Seamounts have incredibly high rates of endemism, sometimes the species that live there are completely unique to that seamount – they don’t even occur on the seamount out next door. Together they form these smaller ecosystem networks that the littlest fish will come and hide in and feed from and then the bigger fish eat them and the bigger fish eat them and up the chain it goes. There’s really solid research now that shows that humpback whales use seamounts to navigate their migration patterns around the globe – a rest stop where they’ll pull in to feed.

I always think it’s amazing when people talk about how the ocean produces half the air that we breathe or how it stores carbon. It’s doing that because of the life in it. It’s the life that exists in the ocean that means it’s able to do those things. So yeah, seamounts are incredible hotspots of ocean life and crucial to the functioning of the whole ocean

What was it like being on the water for so long, did time do strange things?

Sometimes it felt like time was going very slowly and then it would sort of jump forward a couple of hours. Afterwards we couldn’t believe it all happened on the same day. But we had lots of things to pass the time: Christine and I had some lovely chats; we had food; Christine did crochet and I read my book and we had some nice visits as well.

You’ve been campaigning against bottom trawling for a long time – why put yourself in the way of a trawler?

There’s a few things. When I think about the environmental destruction that bottom trawlers cause, I feel physically sick. The scale is enormous. We’ve got all these metaphors for the nets – like you can fit two Boeing 747s inside them and they sometimes drag them 50 kilometres at a time. But when I really pause and connect with how much destruction that is – I just feel that we have to do something about it.

The other thing that really gets me is it’s so out of sight, out of mind. If these guys were felling kauri forests on land, everyone would be up in arms about it. But they’re felling underwater environments that are hundreds, sometimes 1000s of years old, and killing fish that live for 200 years. One of the target species, orange roughy, is an amazing fish. The oldest one on record would have been around when Napoleon Bonaparte was alive.

“One of the target species, orange roughy, is an amazing fish. The oldest one on record would have around when Napoleon Bonaparte was alive.”

These are really ancient creatures and they get away with it, because it’s so far offshore. so deep, you can’t see it, you can’t watch them do it. We don’t see all the destruction either because they throw all the non-target species overboard as “bycatch” – put that in quote marks – because really it’s just a sanitisation of the death and destruction of marine wildlife – dolphins, turtles, corals. It just feels so wrong that they are allowed to do this and that they get so much leeway from our current laws and regulatory bodies to do something that is so damaging for the ocean.

I’d say the third thing for me is when I really connected with how interrelated the ocean ecosystem is. If you take out seamounts, these building blocks, these really core pieces, the whole thing will fall over.

Was there anything in particular you were aiming to achieve through taking this kind of action?

I wanted to draw attention to the whole out of sight, out of mind thing. I want our politicians to take notice. I want them to understand that while I was there physically blocking this, there are tens of thousands of New Zealanders who support this as well – who want to see more protection for seamounts and marine biodiversity. And also it’s about standing up to these companies that are profiting from the destruction of the ocean. We could stop it physically for a number of hours but the bigger picture is that there needs to be regulation that stops bottom trawling because it can’t fall on people like me and a raft to do it. Bottom trawling seamounts is so wrong, so deeply wrong.

“There are tens of thousands of New Zealanders…who want to see more protection for seamounts and marine biodiversity.”

What keeps you interested in ocean protection work?

I think, like most New Zealanders, I have a deep, long standing love of the ocean: swimming when I was growing up, sailing, windsurfing and spending time on the water. I remember being overseas in my early 20s and feeling really suffocated when I couldn’t be near the ocean, which I think is such a common New Zealand kind of experience – because we’re an island nation.

As I started campaigning on ocean issues I got more immersed in understanding the way that New Zealand fisheries are run. I was shocked and really appalled at the amount of control and influence that the fishing industry had over the bodies that are supposedly there to regulate and protect the ocean. And I really felt the sense of outrage, and shock as a New Zealander. Because we often think of ourselves as the good guys and everyone I know loves the ocean and we would think that our government bodies were doing their best to look after that for all of New Zealand. What I saw again and again was the interest of an extractive, damaging, industry being protected over the health of the ocean.

If New Zealanders could really see that, they would be outraged as well – and they are outraged. That’s where so much of the support of this campaign comes from. It made me more passionate about fighting for ocean protection. We need voices that stand up for the ocean because the voice of the industries that damage and extract from it are so loud and have so much influence in the halls of power.

There’s a long history of peaceful, direct action contributing to social change. What’s your take on it?

To actually put your body on the line for something that you really care about is an incredibly empowering feeling. I don’t think any major social progress has been made without peaceful civil disobedience. No one single moment makes change happen. It takes everything together: people signing petitions, advocating to their MPs, protests, writing letters, engaging with policy processes. But there’s something about a willingness to say: “No. No more. Not this.”

“There’s something about a willingness to say: No. No more. Not this.”

Were there any standout or special moments you’d like to share?

It all feels special right? The moments that felt really special were the connection and support from other people – people were walking onto the end of the piers to wave and cheer and people online – we had we had access to social media – and the support that we were getting online…sorry it’s making me a bit emotional…people commenting just to cheer us on and send us love and support and thanks.

There were the three lovely Nelson locals who despite the driving rain and freezing cold got in a little, teeny tiny, boat and came out to visit us and flew flags.

So you felt connected?

Yes. There were two of us on the water but you don’t feel alone. Knowing there are so many people who do really care about this is really heartening. At one point, the rain had come through and everything was wet and cold, a low morale point, and just in that moment we looked out to the water and there was this lovely shag, ducking and diving and swimming: just a tiny little spectre of marine life, and I remember feeling like, ‘yeah, this is totally worth it’.

At home and far out to sea, our oceans are being plundered for profit by the fishing industry through bottom trawling. But what is bottom trawling and why is it so destructive to ocean habitats?

Take Action