This guest blog was written by Matt Peryman (Ngāti Awa). Matt is a Kaupapa Māori Social Scientist who published their Master’s research on plastic pollution last year. Matt currently wears many pōtae to fight plastic pollution and works with several organisations including Reuse Aotearoa, the Aotearoa Plastic Pollution Alliance, and the wider Break Free From Plastic movement.

As Coordinator of the Tāngata Whenua Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty, established to enable the participation of Tāngata Whenua in the development of a legally binding instrument to end plastic pollution, Matt will be attending the next round of discussions in Paris, from 29 May to 2 June.

As the world turns their gaze towards the second meeting of the UN’s Global Plastics Treaty negotiations (INC-2), there has been a lot of kōrero around the idea of a ‘circular economy’. That’s an economic system in which waste is avoided through processes like reuse and refill systems that keep resources and tradable goods in circulation. But is what the petrochemical industry is describing as a ‘circular economy for plastics’, which ultimately means increased recycling, a truly circular solution or just more nonsensical greenwashing?

Due to colonisation and the attempted eradication of Indigenous knowledge, extractive and polluting systems such as colonialism and capitalism have become entrenched and idealised throughout much of the world.

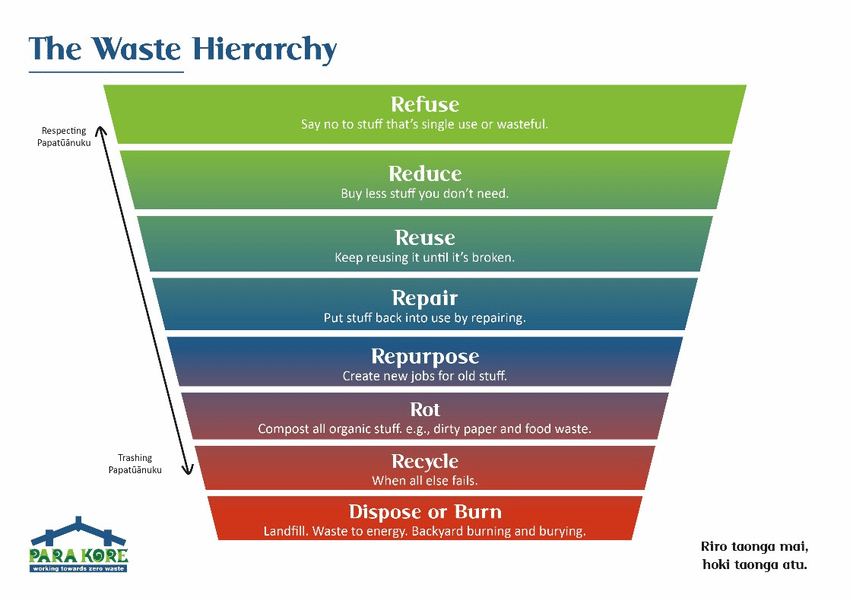

Consequently, the concept of circular economic systems, in which waste is mitigated through established principles and protocols like the waste hierarchy (in modern theory), may seem novel to those accustomed to linear systems that produce waste by design.

For Indigenous Peoples, it’s just the kind of whakapapa-based economics that we’ve been practising for millennia.

Para Kore’s interpretation of the ‘waste hierarchy’ model based on Te Ao Māori. See how low recycling is on the list?

Circular economic models are certainly an attractive alternative to the currently dominant linear systems that pollute our environment and poison our bodies.

However, the idea of a circular economy for plastics is not as green as it might seem, because for the vast majority of the time:

Plastics = polymers + chemical additives

Both of these components present serious ecological and health risks, with polymers (the base material of plastics) never biodegrading but instead breaking apart into hazardous microplastics, which contain and release their chemical additives (used to make plastics translucent, rigid, pliable, coloured, etc) into natural systems, with a wide range of harmful impacts.

99% of plastics are made from fossil fuels which have to be extracted from Papatūānuku, meaning that the production of plastics involves socio-ecological harm at all stages of its lifespan.

This means that as a material, plastics are inherently toxic and waste-producing and are therefore not circular.

Currently, there are at least 13,000 chemical additives used in plastics.

The majority of these are toxic and yet due to a lack of proactive regulation, many of these toxic chemical additives are released when transported, traded, used, and disposed of, eventually making their way into our homes, oceans, soils, bodies, and even placenta.

What are these contaminants doing to our bodies?

As endocrine disruptors, plastics and their chemical additives have the ability to affect our hormones and reproduction cycles. It is for these reasons that my mentor and rangatira of the plastic pollution world, Tina Ngata, frequently describes plastic as a disruptor of whakapapa (genealogical relationships).

Tina also talks about how plastics disrupt mahinga kai (natural food systems) by contaminating food sources, affecting their mauri (life force), their ability to thrive, and reducing biodiversity. As these issues are carried along the food chain, organisms like ourselves ingest them, causing trophic cascades that lead to widespread changes in how our ecosystems function.

This puts undue pressure on local communities who depend on reliable access to food in contaminated places. If plastics are being found in fresh Antarctic snow, it’s evident that no ecosystem or food web has been left unaffected by plastics, which is deeply concerning for future generations.

What happens when industry tries to ‘circularise’ plastics

Over the last few decades we’ve all been sold the myth that by recycling plastics, we are ‘fixing’ the problem of plastic waste. At the same time we’ve all watched as masses of plastics have come to choke our rivers, swamp our oceans, and degrade the air and soil upon which we all depend, though these impacts have disproportionate impacts on Indigenous and other frontline communities.

Furthermore, much of the time countries are unequipped to deal with the various forms of plastics in the market, so ship them off to other (often poorer) countries to deal with in a process called waste colonialism. Even when plastics enter ‘recycling’ systems, they can rarely be recycled back into the same product as the original, so the demand for virgin plastics continues. Often they are downcycled into products of lesser value, perpetuating the linear economy.

The process of recycling plastics has itself been shown to produce microplastics as well as toxic compounds as chemical additives and polymers mix together and pose a myriad of health risks to workers and anyone downstream of recycling centres/disposal sites. This means that even diligently washing your plastics and putting them in the correct wheelie bin won’t prevent the release of dangerous chemicals.

This is not true circularity, but these are the kind of practices that the plastics and petrochemical industries promote as circular solutions to the plastic pollution crisis in Global Plastics Treaty negotiations. For industry, a ‘circular economy for plastics’ translates to increased recycling without any reduction in plastics production, which only perpetuates the extractive linear economy and the pollution of Papatūānuku.

Clearly recycling alone cannot prevent plastic pollution. This is a truth that industries and governments alike need to reckon with if we are to ever get plastic pollution under control via the minimisation of plastic production and the uptake of truly circular systems (like reuse and refill).

Compostable / bioplastics are another false solution

As people become more aware of this, some companies are taking the opportunity to develop ‘compostable’ alternatives to single-use plastics known as bioplastics. These are widely marketed as being home compostable or at least, industrially compostable (an issue for another day), despite often containing chemical additives that make them operate similarly to fossil fuel-based plastics.

Bioplastics also preserve single-use models that we really should dispose of in favour of reuse, refill, and other solutions high on the waste hierarchy. However, it is also important to remember the inherent risks associated with plastics when considering materials for systems of reuse, refill, and repair.

It is essential that we debunk these industry falsehoods as well as the idea that a circular economy for plastics can ever be safe, non-toxic, or waste-free.

We must reclaim the concept of ‘circularity’ and ground it in reality by incorporating Indigenous knowledge and values – mātauranga and tikanga Māori here in Aotearoa – in relation to the impacts of linear systems on local contexts and environs. From there, we can understand that if a system, practice, or product entails a risk of releasing harmful contaminants, it is not tika, and it is definitely not circular.

We must also base our approach to the Global Plastics Treaty in humility by acknowledging the limitations of human knowledge, which calls for a precautionary approach to the manufacturing of both polymers and chemical additives that proactively prevents the production of toxic materials.

This applies not only to manufacturing but to the entire life-span of plastics, as waste management practices commonly purported by industry as greener alternatives to landfills, such as incineration and waste-to-energy.

We also need to explore what circularity means in local contexts, responding to local issues with local knowledge, rather than making grand universal claims of best practice in spaces that are not our own.

At this point, one thing needs to be made clear:

Our focus should not be on how to make plastics circular, it should be on taking (most of) them out of circulation.

Nations must be ambitious and support a Global Plastics Treaty focused on significantly minimising plastic production and support truly circular solutions (like reuse and refill), rather than focusing on how to sustain an industry (and indeed, an economic system) that places profits above our planet’s collective health and well-being.

Our collective transition away from plastics must be just and ensure that those who currently need plastics for medical reasons are supported, unless or until safe and non-toxic alternatives are available. Nations and industries should be looking at how they can support and provide reparations for those most disproportionately affected by plastic pollution, including waste pickers, Indigenous Peoples, and other frontline communities.

May everyone working toward a Global Plastics Treaty be courageous and unwavering in their actions to stop the compounding intergenerational impacts of runaway plastic pollution on our already-vulnerable tamariki and the world we want to leave for them.

Kia kaha, kia māia, kia manawānui.

Call on the NZ Government to stand firm and support a strong global plastics treaty.

Take Action