A few months ago I had the privilege to watch an advance screening of the extraordinary documentary on Greenpeace’s early history, How to Change the World. Jerry Rothwell’s compelling film brings to life an important and formative chapter of how Greenpeace began and where its roots lie, as seen through the eyes of late cofounder Bob Hunter.

The film is rich with passionate people who founded this intrepid organization, and overall I felt a sense of connectedness through my work as a forest campaigner to the inspiring legacy left by such a small but powerful and dedicated group of women and men.

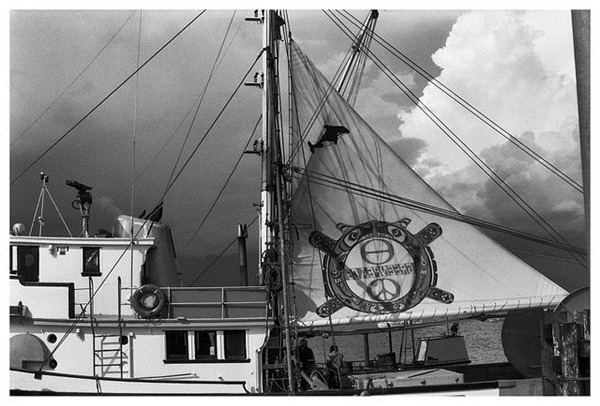

However there was one image seen throughout the film that brought both a knowing smile and a slight wince. This image was that of the old Greenpeace ecology and peace logo encircled by a double-headed serpent (at the time thought to be two whales).

Many times seen emblazoned on Greenpeace ships, office windows, etc, the image is in fact an altered, hybridized version of an ancient crest called the Sisiutl and it is sacred to (amongst others) the indigenous Kwakwaka’wakw, Heiltsuk, Nuxalk and Nuu-cha-nulth peoples of the Pacific Northwest.

How this symbol came to appear most prominently on the sail of the first Greenpeace ship, Phyllis Cormack, and continues to be part of the Greenpeace identity is an intimate and intrinsic part of Greenpeace’s origin story. It is also a story of cultural appropriation. And my job for the past year has been managing the Sisiutl Renewal Project, with the goal of both restoring the dignity of the crest at Greenpeace and the spirit with which it was shared with us.

The Sisiutl Renewal Project is one small but important step towards decolonizing our organization. Other steps include the recently developed policies Greenpeace USA and Greenpeace Canada each now have in reconciling and working with indigenous peoples.

But let’s go back to 1971, to Greenpeace’s very origins.

Greenpeace’s First Mission

The organization’s first campaign was protesting U.S. nuclear testing at Amchitka, Alaska. To do this, a small fishing vessel, the Phyllis Cormack, was chartered to take a crew of a dozen to the front lines of the nuclear test.

Along the way it stopped at the indigenous community of Alert Bay (or ‘Yalis, its actual Kwakwaka’wakw name) on Cormorant Island, located on Canada’s west coast. ‘Yalis is located in the traditional territory of the ‘Namgis First Nation, and here members of other several Kwakwaka’wakw nations gifted the crew (which included Greenpeace founder Bob Hunter) with wild coho salmon and a blessing for their journey. This also happened to be the young organization’s first interaction with an indigenous community.

As they continued on to Amchitka, the US Coastguard prevented the Greenpeace crew from going any further without a proper entry visa, and eventually with deflated spirits they headed back to Vancouver, British Columbia. En route, the Phyllis Cormack stopped once again in ‘Yalis (Alert Bay), where the crew was invited to a celebration in their honor at the ceremonial Big House.

They were acknowledged by members of the ‘Namgis and other Kwakwaka’wakw nations for their courage in standing up to the Unites States military industrial complex with a special ceremony that included song, dance and food. The crew had Kwakwaka’wakw traditional regalia placed on them, with eagle down on their heads, and they even participated in one of the ceremonial dances – the Peace Dance (or Tla’sala, in the Kwak’wala language).

This was all a great honor. Bob writes in Warriors of the Rainbow that the crew, “were made into brothers of the [Kwakwaka’wakw] people.”- or, in other words, they were ceremonially adopted by the community. All of this uplifted their spirits.

[I should clarify that ’Kwakwaka’wakw’ (mistakenly referred to in the recent past as ‘Kwakiutl’) is not one First Nation but rather are the people who speak Kwak’wala, and so there are many nations in the region – seventeen by today’s count. The people that Bob and the crew encountered to and from ‘Yalis, in addition to the ‘Namgis, would have belonged to any of these seventeen nations].

Greenpeace Meets the Sisiutl

Shortly after that important ceremony Bob was given a blue cloth with a Sisiutl crest by a leading member of one of the Kwakwaka’wakw communities (according to some of the original crew members, this person was James Sewid, who came from one of the surrounding villages and who was also the first elected Chief Councilor of the ‘Namgis First Nation at Alert Bay).

The Sisiutl symbol is a powerful spiritual crest with many origin stories amongst various coastal First Nations of British Columbia, including the Kwakwaka’wakw. The Sisiutl itself is a supernatural creature with two serpent heads, one at each end and a human head in the middle. For the Kwakwaka’wakw, the Sisiutl symbolizes the balance of life between good and evil. Wearing it and telling its stories helps warriors and healers with their work. It is also used to protect canoes and Big Houses.

Only certain Kwakwaka’wakw individuals and families (as well as other coastal First Nations) have the cultural and spiritual rights to display the Sisiutl in ceremonies, so to have the Sisiutl shared with Bob and Greenpeace was a huge honor.

We don’t actually know at this point what the original Sisiutl on that piece of blue cloth looked like or why it was shared with Bob. We can only surmise that given its meanings of protection and general association with the sea and warriors that it was a blessing or gift intended to help the Greenpeace team succeed in its important work after the Amchitka campaign.

What we do know is that its form was dramatically altered sometime between 1974 and 1975, when Bob and other Greenpeace members decided to use it as the basis for a new symbol for the anti-commercial whaling campaign that was to launch in 1975. Bob wrote in Warriors of the Rainbow that he believed Greenpeace had permission to adapt the crest because the original crew had been adopted into the Kwakwaka’wakw during the 1971 ceremony.

In How to Change the World you can see rare footage of the altered Sisiutl/Greenpeace symbol being painted on the Phyllis Cormack’s sail for the first time, and then subsequently worn as t-shirts by Greenpeace volunteers and staff, on office walls, etc.

And, interestingly, there are also photos of Bob showing a tattered flag with the hybrid Sisiutl/Greenpeace symbol to Kwakwaka’wakw elders when he and other crew members of the anti-whaling campaign returned to Alert Bay later in 1975 for another ceremony at the Big House. Bob recounts in Warriors of the Rainbow that they returned to Alert Bay as a way to honour the Kwakwaka’wakw, “to give them the flag we had flown since embarking on the voyage to save the whales”.

But in making that fateful decision to adopt and adapt the Sisiutl as Greenpeace’s own, the sacred crest was in fact inappropriately altered and hybridized, its meaning forever changed.

With the benefit of hindsight, and with greater understanding today of Kwakwaka’wakw customs and traditions, we believe that while the Sisiutl symbol itself was shared with Greenpeace, we didn’t have the right to alter it and make it our own – especially to the degree that the hybrid continues to be displayed in Greenpeace offices around the world.

In addition to the continued widespread use of the altered symbol there are also inaccurate stories of how we came by it, and misunderstandings of what the Sisiutl actually is. For example, over the years Greenpeace has believed, and has communicated out to the world, that the Sisiutl symbol is of two whales forming the ‘infinite cycle of nature’, and this is incorrect.

Restoring the Sisiutl Crest

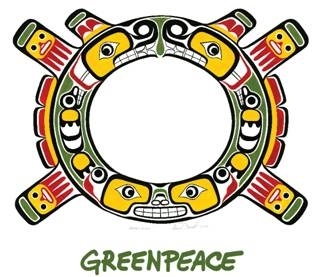

With all this in mind, Greenpeace Canada with support from Greenpeace International approached representatives of Kwakwaka’wakw communities to inquire about redesigning or restoring the Sisiutl to a more culturally appropriate form, and to explore the possibility of having it re-dedicated by representatives of these First Nations in the most meaningful and culturally appropriate way. One representative suggested we commission well-known Kwakwaka’wakw artist and cultural leader Beau Dick to help us with this important task. We approached Beau, and he agreed to redesign the Sisiutl Crest for our use in perpetuity, but with our written promise to never alter it again.

Following protocol, we committed to a re-dedication ceremony of the Sisiutl crest at a potlatch that would also renew ties with the Kwakwaka’wakw hereditary chiefs. We again returned to ‘Yalis (Alert Bay) in March 2015, and there we had the honor and privilege of having the renewal ceremony take place at the Big House, at a potlatch hosted by the Willie Family, an important hereditary family in region (see family representative Mike Willie’s blog).

Greenpeace International Executive Director Kumi Naidoo and Greenpeace Canada Executive Director Joanna Kerr along with staff, joined surviving members of the original 1971 crew and Mike Willie, on the potlatch floor for the special ceremony. Kumi and Joanna addressed the many hereditary chiefs and members of Alert Bay and surrounding communities, and apologized for the misuse and misappropriation of the original Sisiutl crest. Beau’s redesign of the Sisiutl was then revealed, with this historic occasion witnessed by all in attendance, including a few of the community members who were present at the 1971 ceremony as youngsters.

Dancing the Tla’sala – Transcending Time and Space

Later that night, Mark Worthing (who originally brought the altered Sisiutl/Greenpeace symbol to our attention and has been crucial to the renewal project) and myself were taken to the back area of the Big House.

I felt deeply moved and nerve-wracked by that moment, disbelieving of what was happening to me as they placed traditional regalia on me, with the headdress sitting firmly on my glasses and eagle down atop it beginning to fall gently all around me.

We were given a quick lesson on how to dance the Peace Dance before being ushered, with several community members, onto the ceremonial floor. And on the floor, I just lost track of time and place and, well, self.

We were given a quick lesson on how to dance the Peace Dance before being ushered, with several community members, onto the ceremonial floor. And on the floor, I just lost track of time and place and, well, self.

Barbara Stowe, daughter of Greenpeace co-founders Irving and Dorothy Stowe, later said to me: “That was one of the most resonant and moving experiences of my life. The honor accorded to you and Mark was obvious, and through you this community had just accorded enormous respect and honor to Greenpeace.”

That moment, in echoing that historic day in the fall of 1971 when the crew of the Phyllis Cormack were also asked to dance the Peace Dance in full regalia, I believe also helped reinvigorate the direct ties between our Greenpeace community and the Kwakwaka’wakw. We once again have become interconnected deeply and ceremonially with the Kwakwaka’wakw as a whole.

The Sisiutl Made Whole, Comes to the Greenpeace Fleet

As meaningful and moving as that ceremony and potlatch was, equally as important was re-introducing the new Sisiutl crest to our fleet of Greenpeace ships (especially since that is how our relationship with the Sisiutl began- with our first ship, the Phyllis Cormack).

It was very serendipitous then that one of our vessels, the Esperanza, happened to be in my region a few months after the Willie Family Potlatch. We took advantage of this and organized a ceremonial event in the Squamish First Nation traditional territory of North Vancouver, British Columbia.

Squamish representatives officially welcomed the Esperanza. Beau Dick and his delegation from Kwakwaka’wakw communities dressed in full regalia formally blessed the ship and presented the renewed Sisiutl Crest, in the form of a flag, to ship’s Captain Pep Barpal and others from the Greenpeace community. The flag with the new Sisiutl Crest and the Greenpeace logo placed beside it was then hoisted to fly proudly alongside the international Greenpeace flag. As a result, the renewed Sisiutl has now been brought back in a culturally appropriate form to the Greenpeace fleet.

Rewriting Our Story

How to Change the World is an important film that materially demonstrates how a small group of impassioned individuals can make a difference in the world, but in a way that also authentically reveals all-too human frailties. These frailties in some way also helps underscore what happened to the Sisiutl – in the desire to do good in the world, ego-driven decisions sometimes lead to mistakes that leave lasting legacies that need fixing.

We acknowledge the heroics of those incredible people involved in the heady days of the organization’s origins, and in the case of the Sisiutl we must now also take responsibility for the legacy of its cultural appropriation. This is one small but important step at reconciliation with this particular group of indigenous people.

Aside from following proper protocols and undertaking ceremonies that now authorize us to carry the new Sisiutl, we are rewriting the story of how we came to the symbol and what it actually means (this blog post is a means towards that end). We plan to circulate not only prints of Beau Dick’s Sisiutl crest as we retire the old hybrid one, but also the newly corrected narrative of the Sisiutl-Greenpeace story, to Greenpeace offices around the word. As I mentioned previously, there is significant misunderstanding of what the Sisiutl means and how we came by this amongst the Greenpeace community so we will continue in our efforts to reconcile the legacy of these past beliefs and mistakes.

Managing the Sisutl Renewal Project has a been deeply meaningful journey not only towards helping the organization decolonize a symbol sacred to Pacific Northwest peoples that is intertwined with Greenpeace’s identity, but also towards decolonizing my own mind and thinking processes. It’s an ongoing process. It has also been a great metaphor for a mind bomb. Bob would be proud.

——–

Eduardo Sousa is senior forest campaigner for Greenpeace Canada. He has been working these past seven years to finalize the Great Bear Rainforest Agreements, and helping protect the remaining large intact forests of Clayoquot Sound – both in unceded traditional territories of over thirty First Nations on the west coast of Canada.

Discussion

Thank you so much for this article! In the 1970’s I was a member of the Netherlands’ support-group for Native American Rights - in that time there were support-groups like ours in all western European countries, from Sweden, to Switzerland and Austria, to Spain. So we knew that Greenpeace got its logo from the Peoples on the Westcoast. I bought the Greenpeace totebag, used it a lot, but also cared for it, as the print is so beautiful. This week I retrieved it from a storage box and washed it, bc the cotton fabric makes it excellent for keeping homemade bread. And then I thought, "what was the meaning again of this Kwakiutl (sorry!!!) art". Neither Google nor Greenpeace offered useful information - but your story is the best I could hope for!