Toru Anzai is a former resident of Iitate, a small village in Fukushima, Japan, and dearly missed the bamboo shoots that grew in his hometown. During autumn, the bamboo shoots would blanket the mountains that overlooked the residents’ homes in the village. The residents would climb the mountains, gather the plants, and prepare them for dinner. But ever since that tragic day, no one climbed the mountains, and the wild plants vanished from their dinner tables. For Anzai, the bamboo shoots became sad reminders of what used to be.

Anzai remembers the day as the “black snow” day. He heard the explosions on 12 March, 2011. Black smoke rose from the Fukushima nuclear power plant, and the smell of burning iron pervaded the village. It started to rain. The rain turned into snow. The snow was black.

The black snow filled Anzai with an ominous dread, and soon, his fears became reality.

After the black snow shrouded the village, Anzai described in an interview how he started to feel throbbing pain on his skin. It was almost like being sunburned after sunbathing for too long. Both of his legs darkened then peeled in white patches. The only remedy to the peeling was applying medicinal ointment.

Soon after, his entire body began to suffer. The headaches came, followed by shoulder pains. Then the hair loss occurred. Three months after the disaster, he left behind his home and evacuated to survive. Unfortunately, the tragedy did not end there.

Three years later, Anzai started having strokes and heart attacks. A stent was placed in his blood vessel; the tube held open his narrowed blood vessel and kept the blood flowing to his heart. With treatment, his pain somewhat subsided, but whenever Anzai visited Iitate, the pain throughout his entire body relapsed. While these symptoms have not been conclusively connected to the radiation exposure, Anzai believed that they were the realities of the black snow day.

Anzai’s temporary housing was very narrow and consisted of a living room and a bedroom. He had moved into this subsidised housing complex eight years ago. He was one of the first of the 126 families. Often, evacuees gathered around the common area and shared fond memories of their hometowns with each other. Whatever solace could be found, the evacuees found it in each other.

Since allegedly completing the decontamination operation in Iitate, the Japanese government have been urging people to return to their village. In fact, Fukushima prefectural government had ended housing subsidies this past March, and by the end of the month, most people had left the complex. Only around ten families were still looking for a new place to live.

Absently gazing into the dark, clouded sky, Anzai spoke bitterly. “I was kicked out of my hometown for doing nothing wrong. It was heartbreaking. Now, Iitate is polluted, and some of my neighbours have died. When the government asked me to evacuate last minute, I left. Now, they want me to go back. Back to all of the radioactive contamination. I’m so angry, but I don’t know what to do. We have repeatedly petitioned the government, but they’re not willing to listen. Our government has abandoned us.”

Prior to the nuclear incident, there were about 6,300 residents in Iitate. Eight years later, only a little over 300 evacuees have returned at the government’s persistent urging. Most of the returning residents were elderly, aged 60 or older. Even counting the non-natives who had recently relocated to the village, the total figure hovered around only 900 residents.

Iitate’s old and new residents are exposed to radioactive substances on a daily basis. The Japanese government claimed to have completed the decontamination work, but a full decontamination is impossible due to the village’s terrain. More than 70% of Iitate is forest, and unlike in the farmlands, the removal of contaminants that have fallen among the mountainous forest is nearly impossible.

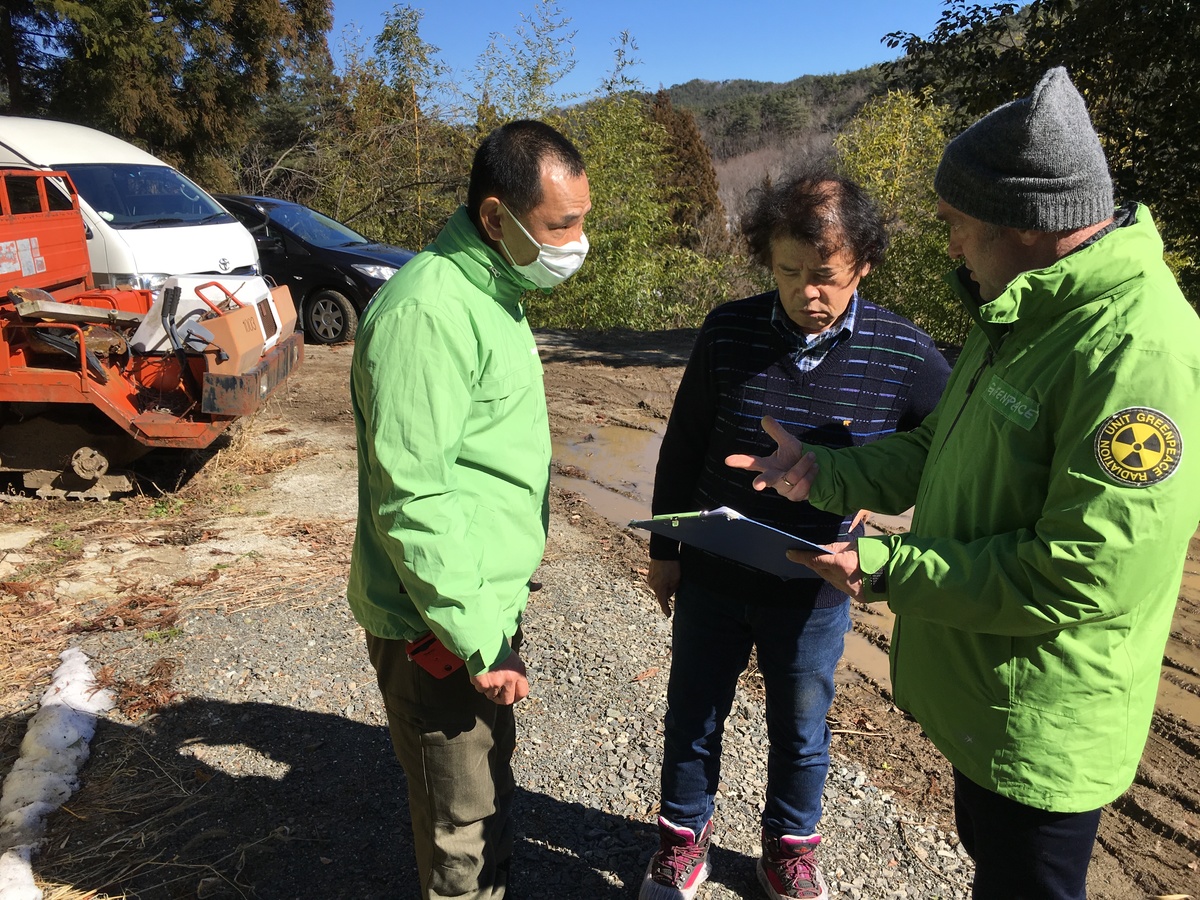

Each year, Greenpeace Germany conducts extensive research on Fukushima villages including Iitate. The findings confirm that the radiation exposure in these villages exceeds the established international safety standards. Anzai believes that the Japanese government is behind the forced homecoming of the Iitate residents.

“The government hopes to publicise good news: the nuclear accident has been dealt with, and the residents have returned home. People who had no choice but to leave are now being pressured to return and put their lives on the line,” lamented Anzai.

The Japanese government hopes to release more than one million tonnes of highly radioactive water into the Fukushima coast. If the contaminated water becomes flushed into the ocean, the contamination will only add to the harm already inflicted by the Fukushima accident. Furthermore, the ocean currents will shift the radioactive materials through the surrounding waters including the Pacific Ocean.

The industrial pollution and toxins have already caused much distress to our oceans. Discharging the Fukushima’s radioactive water will only worsen the situation, and we cannot, and should never, let this happen.

Sean Lee is Communication Lead at Greenpeace Korea.

Edit & Translation: Jiyun Choi is Communication Coordinator at Greenpeace International.