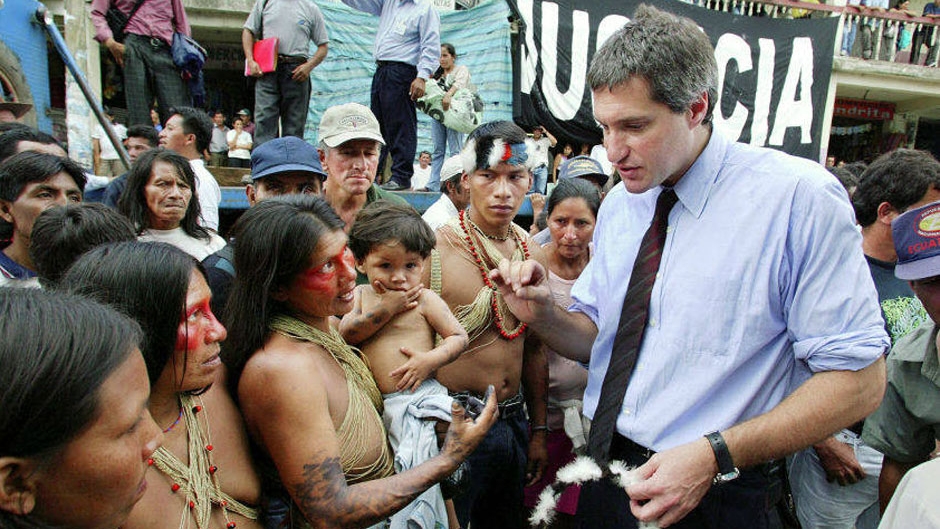

In the fall of 2016, I travelled to Ecuador’s Amazon Basin, where I met Indigenous communities and Campesino farmers whose land had been polluted by toxic oil waste. They had won a landmark court judgement against the Chevron Corporation, but the company refused to pay. I visited the one, tiny clinic serving thousands of cancer patients, and also met the victims’ American lawyer, who has spent the last 27 years defending their rights.

You’ve probably never heard of Steven Donziger, but I believe history will place Donziger – a man vilified by his corporate opponents – alongside Gandhi, Susan B. Anthony, Martin Luther King, Vandana Shiva, and other leaders of human rights and environmental resistance to corporate malfeasance and arrogance.

At the time of writing, Donziger has been trapped in home detention for six months. He has still not actually been convicted of any crime. By all accounts, he appears to be a political prisoner of a private corporation bolstered by a cooperative federal judge.

We live in an era of vast ecological decline and social disparity. Toxins poison all life on Earth, about half of Earth’s Pleistocene forests are gone, and thousands of species go extinct every year. Meanwhile, according to the UN, over nine million people starve to death annually, with over 800 million people suffering from chronic malnourishment. In December, an eye-witness to violence against Indigenous people in Brazil concluded, “There is no environmental justice without social justice.”

The link between ecological protection and human rights is evident in Ecuador’s Amazon basin, where massive oil pollution has destroyed forests and farms and left some of the world’s poorest people with birth defects and a cancer epidemic. In 1993, Ecuador’s Frente de Defensa de la Amazonía (FDA), representing 30,000 victims of Chevron’s toxic oil waste, asked Donziger to help them win compensation for what is likely the largest oil-related human disaster in history.

Eight years ago, Donziger and the FDA legal team won the largest court judgement in history for human rights and environmental violations, a $9.5 billion verdict against the Chevron Corporation. Following this verdict, Chevron sold their assets in Ecuador, fled the country, threatened the plaintiffs with a “lifetime of litigation” if they attempted to collect, and – according to internal Chevron memos – launched a retaliatory campaign to “demonize” Donziger. From Chevron’s subsequent actions, it appears that they also intended to impoverish him so that he could no longer work to collect the judgement in other jurisdictions.

The public defender

” class=”wp-image-28742″/>After graduating from Harvard Law in 1991, Donziger became a Public Defender, representing young people in Washington DC. In Iraq, during the first Gulf War, Donziger helped document civilian casualties and co-authored a report adopted by the United Nations. Since 1993, the Ecuador pollution case has consumed his legal career.

The ecological and human rights tragedy began in 1964, when Texaco (now Chevron), discovered oil in Ecuador. The oil company ignored routine waste regulations, dumping some 16 billion gallons of toxic wastewater into rivers and pits, polluting groundwater and farm land. According to Amazon Watch, Chevron flouted environmental regulations to save an estimated $3 on every barrel of oil produced, earning an extra $5 billion over 20 years.

In 1993, in a New York federal court, Donziger and the legal team filed a class-action lawsuit against the company. In 2000, Chevron bought Texaco, insisted that the case be moved to Ecuador, and filed 14 affidavits swearing to honour Ecuador’s judicial system as competent and suitable to adjudge the case.

At the trial in Ecuador, 54 judicial site inspections confirmed that Chevron caused oil contamination in violation of legal standards. The reports showed that the average Chevron waste pit in Ecuador contained 200 times the contamination allowed by US and world standards.

Some 900 illegal waste pits leached into the water table, local drinking water became noxious, and citizens became ill. The contamination contained illegal levels of barium, cadmium, copper, mercury, lead, and other metals that can damage the immune and reproductive systems and cause cancer. Children were born with birth defects.

In 2011, after eight years of trial and deliberations, hampered by Chevron’s delaying tactics, Donziger and his team won the court case in Ecuador. Two appeals courts and the nation’s Supreme Court, the Court of Cessation, confirmed the decision. A total of 17 appellate judges ruled unanimously that Chevron was responsible for the contamination and owed Donziger’s clients $9.5 billion. Donziger expected his clients to receive medical attention and land reparations.

However, Chevron defied the Ecuadorian courts, where they insisted the trial be held. They refused to pay the debt, began defaming Ecuadors’ courts, and initiated a retaliatory attack on the victims and on Mr. Donziger.

“Demonize Donziger“

To attack Donziger, Chevron hired private detectives to shadow him, his family, and supporters. They hired one of the world’s most notorious law firms, the avowed “corporate rescue” specialists Gibson, Dunn and Crutcher. The High Court of England censured Gibson Dunn for fabricating evidence in a previous case. Judges in California, Montana, and New York have censured Gibson Dunn for witness tampering, obstruction, intimidation, and “legal thuggery.” In Ecuador, Gibson Dunn lawyers even threatened judges with jail if they ruled against Chevron.

To “demonize” Donziger, the Gibson Dunn lawyers filed a civil RICO racketeering case against him and two Ecuadorian plaintiffs, Secoya Indigenous leader Javier Piaguaje and farmer Hugo Camacho. Judge Lewis Kaplan – widely viewed as being friendly to large corporations – agreed to hear the unusual case, which would become one of the most notorious intimidation lawsuits (SLAPP suits) of all time. Prominent trial lawyer John Keker, who had represented Donziger, called the Kaplan trial a “Dickensian farce” driven by Kaplan’s “implacable hostility” toward Donziger.

Kaplan had spent 24 years at the firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, known for helping large banks such as Citigroup escape fraud charges. In a tax shelter fraud case against the giant corporate accounting firm KPMG, Kaplan threw out cases against 13 indicted executives, even though the company had admitted criminal wrongdoing and paid $456 million in penalties.

In the attack on Donziger, Kaplan authorized Gibson Dunn to subpoena and depose dozens of people who had helped fund the case, harassing innocent citizens as if contributing to pay court expenses was illegal. When Kaplan waived normal media confidentiality, demanding that filmmaker Joseph Berlinger turn over outtakes from his 2009 documentary, Crude: The Real Price of Oil, a media coalition — including The New York Times, NBC, and HBO — filed a First Amendment objection with the court.

Kaplan, and Chevron’s Gibson Dunn lawyer, Randy Mastro, repeatedly insulted the courts in Ecuador. Mastro called the Ecuador courts “a sham.” Kaplan claimed the Ecuador trial “was not a bona fide litigation,” and he insulted the 30,000 class-action victims, calling them “so-called plaintiffs.”

By imposing an impossible deadline, Kaplan invoked a technicality to claim that Donziger had “waived” all attorney-client privilege, and insisted he turn over 17 years worth of confidential communications with his clients. Defense attorneys called this “the most sweeping forced production of privileged documents in history.” The corporate-friendly judge barred the defense from even mentioning “pollution in Ecuador,” which, he said, was “not relevant.”

On the eve of the RICO trial, Chevron dropped its financial damages claim, allowing Kaplan to dismiss the jury of impartial fact-finders, so he could decide the outcome himself. “Chevron,” said Donziger, “apparently panicked at the notion of trying to sell its fraud claims to anyone other than Kaplan.” Kaplan allowed anonymous witnesses from Chevron, which defense attorneys said violated “basic legal principles” and would “be right at home in the Spanish Inquisition.”

Finally, Kaplan accepted Chevron’s star witness, Alberto Guerra, a disgraced former Ecuadorian judge, who had been removed from the bench for accepting bribes, and who received some $2 million in cash and benefits from Chevron, in violation of legal and ethical principles. In exchange, Guerra claimed that Donziger had approved a “bribe” to an Ecuadorian judge and had written the final court ruling for the judge, which he allegedly gave to him on a computer drive. No corroborating evidence was ever offered. Guerra later admitted lying to Chevron about these facts to extract a bigger reward for his testimony, and a forensic investigation of the Ecuadorian judge’s computer proved that he had lied. By all appearances, the entire story had been fabricated to frame Donziger.

Nevertheless, without a jury, Judge Kaplan accepted Guerra’s contrived evidence and “convicted” Donziger of fraud. Finally, Kaplan ordered Donziger to turn over his computer and cellphone for review by Chevron. Since this order violated basic attorney-client confidentiality, Donziger rightfully refused to obey Kaplan’s bizarre order until the court of appeals could decide the issue.

Outraged, Kaplan charged Donziger with criminal contempt. However, the order and the contempt charge were so outrageous that the New York prosecutor’s office refused to take the case. Kaplan defied the state legal authorities and appointed a private lawyer to act as prosecutor, who in turn ordered that Donziger be placed under “pre-trial home detention.”

Which is where he has been for the last six months, far longer than the longest sentence ever imposed on a lawyer charged with contempt. His lawyer believes he is the only person in the United States in pre-trial detention on a misdemeanor charge.

The great injustice

“Mr. Donziger came to our aid at a time when our communities had been poisoned, and we were up against one of the largest corporations in the world,” said Luis Yanza, cofounder and president of the FDA. “Thanks to Mr. Donziger’s generous work, three layers of Ecuador courts found Chevron guilty of deliberately dumping billions of gallons of toxic oil waste into the Amazon rainforest. Chevron has refused to pay the court-ordered compensation, and has instead set out to, in their own words, “demonize Mr. Donziger.”

Donziger’s lawyer, Andrew Frisch, has stated that “Chevron’s case … rested on the paid testimony of a witness who was paid over $1 million. He admitted to changing his story multiple times to sweeten his deal with Chevron.” Frisch stated that Judge Kaplan’s rulings, “have been contradicted in whole or in part by seventeen appellate judges in Ecuador and ten in Canada, including in unanimous decisions of the highest courts in both countries.

“Mr. Donziger is a person of integrity,” attorney Deepak Gupta testified at Mr. Donziger’s New York bar hearing. “Mr. Donziger is indisputably an advocate dedicated to helping Indigenous Peoples and local communities of the Amazon play equally on the same fields of civil litigation … dominated by the Chevrons of the world. I have never seen a judge whose disdain for one side of the case was this palpable. A great injustice was being done.”

“I did not set out to be an environmental lawyer,” says Donziger. “I simply agreed to seek a remedy for 30,000 victims for the destruction of their lands and water; to seek care for the health impacts including birth defects, leukemia, and other cancers; and to help them restore their Amazon ecosystem and basic dignity. I expected Chevron to fight back, and they had the opportunity to do so during the eight year trial in Ecuador. I did not, however, expect the lengths they would go to to attack me personally, attack my family, attack their victims, and defy a legal judgement that they pay for their crimes, as proven in a court of law.”

Those affected by Chevron’s pollution are modest, honourable, self-reliant people. They had no money to hire lawyers. Donziger solved that problem by getting donors and investors to buy small portions of the judgment to pay case expenses. He recruited leading litigators in Ecuador, the United States, and Canada. “This is the first time that Indigenous Peoples and impoverished farmers had access to this level of capital and legal talent, which is why Chevron is so terrified of the model,” said Donziger. “Chevron not only wants to win the case, they want to kill the very idea of the case.”

“This case is not just about the fate of Mr. Donziger,” says Simon Taylor, director of Global Witness in London. “A lasting injustice to him would chill the important work of other environmental and corporate accountability advocates engaged in similar legal battles against powerful corporations. This is of particular concern, given our work on the escalating threats and escalating killings and judicial harassment of environmental defenders.”

Because of the Kaplan decision, and lobbying by Kaplan and Gibson-Dunn lawyers, the bar grievance committee in New York suspended Mr. Donziger’s law license without a hearing. However, bar referee and former federal prosecutor John Horan called for a hearing and recommended the return of Mr. Donziger’s law license. “The extent of his pursuit by Chevron is so extravagant, and at this point so unnecessary and punitive,” Horan wrote. “My recommendation is that his interim suspension should be ended, and that he should be allowed to resume the practice of law.” Donziger responded that, “Any neutral judicial officer who looks objectively at the record almost always finds against Chevron and Kaplan,” said Donziger. “The tide is turning and the hard evidence about the extreme injustice in Kaplan’s court will be exposed.”

In spite of getting his law license back, Steven Donziger remains in home detention, wearing an ankle bracelet. It now appears that the only fraud in this case is that committed by Chevron’s retaliatory attack against Mr. Donziger and his clients, and by Chevron’s paid witnesses, who gave fabricated evidence. His work for the Indigenous and farmer communities of Ecuador’s Amazon is work for all of us. His compassion and perseverance provide an enduring model of citizen commitment to ecology, justice, and common decency.

Sources and Links:

Declining species: (1) Biomass Study, Bar-on, Phillips, Milo: Proceedings of the US National Academy of Sciences, May 21, 2018; Article #17-11842; PNAS; and (2) The Extinction Crisis,” Center for Biological Diversity.

Global hunger: (1) “Global hunger continues to rise,” UN, World Health Organization; and (2) “Global Hunger Facts,” Mercy Corps.

Impacts of Chevron oil pollution in Ecuador: (1) Indigenous communities affected: ChevronToxico; (2) health impacts on Indigenous groups: independent health studies cited by the court. (3) Summary of evidence against Chevron found by Ecuador’s courts: evidence; (4) Environmental Impacts of Chevron in Ecuador: ; (5) Video, Chevron in Ecuador: video on the case. (6) A Rainforest Chernobyl: ChevronToxico;

Ecuador Supreme Court unanimous judgement vs. Chevron.

Frente de Defensa de la Amazonía (“Amazon Defense Coalition”), representing the 30,000 victims of Chevron’s oil pollution. FDA.

Gibson-Dunn law firm censures: (1) “Chevron Law Firm Gibson Dunn Blasted by High Court of England For Falsifying Evidence: Chevron Pit, March 25, 2015.” (2) Gibson Dunn firm frequently criticized and sanctioned by courts for crossing the ethical line. (3) Montana Supreme Court $9.9 million fine against Gibson-Dunn: Montana Supreme Court document, 05-378, 2007, MT 62. (4) “Gibson Dunn’s Ecuador narrative crumbling; the firm’s unethical tactics”: The Chevron Pit.

Chevron’s Gibson Dunn lawyers threatened Ecuador’s judges with jail.

“Amnesty International Demands Criminal Investigation of Chevron Over Witness Bribery and Fraud in Ecuador Pollution Litigation;” referral of Chevron and Gibson Dunn lawyers to US Department of Justice by Amnesty International et al., allegations that Chevron and U.S. Judge Kaplan used false testimony to attack the Ecuador judgment and human rights defender Donziger; makechevroncleanup.com, July 2019.

“Chevron’s Threat to Open Society,” a 2014 letter signed by over 40 US environmental and civil rights organizations (including Greenpeace, Amazon Watch, Rainforest Action Network, Sierra Club, and Friends of the Earth) stating that Chevron’s tactics “targeted nonprofit environmental and Indigenous rights groups … designed to cripple their effectiveness and chill their speech.”

Shareholders rebuke Chevron, June 2017, Amazon Defense Coalition

How the US courts got it wrong: rebuttal, Chevron RICO case. Steven Donziger

Deepak Gupta brief appealing the Kaplan RICO judgment, with an excellent fact section that covers the case history: Gupta Wessler, pdf, July 2014.

Chevron’s bribery and fabrication of evidence in U.S. courts to evade Ecuador judgment

Alberto Guerra’s false testimony: (1) Chevron falsification of Guerra’s testimony: background and legal motion; (2) Chevron’s Star Witness Admits to Lying in the Amazon Pollution Case,” Eva Hershaw, Vice News, Oct 26 2015. (3) Forensic results on Ecuador judge’s computer: “Expert rebuttal Report of Christopher Racich, Issuu Documents, December, 16, 2013. (4) Adam Klasfeld, “Ecuadorean Judge Backflips on Explosive Testimony for Chevron,” Courthouse News Service, 2015. (5) Guerra admitted lying to Chevron about alleged bribes: US/Ecuador arbitration transcripts, pages: 630-31, and 744

Judge Lewis Kaplan bias and legal errors: (1) Mandamus Petition to recuse Judge Kaplan, Patton Boggs law firm, ChevroninEcuador.org, June 2011; (2) Mandamus Petition to recuse Kaplan, 2013: ChevroninEcuador.org.

“Collateral Estoppel,” by Harvard Law Professor Charles Nesson, The Harvard Law Record, December 6, 2019: How the New York courts and bar have attempted to silence Steven Donziger and hide the facts of Chevron’s Ecuador pollution.

Letters from lawyers Andrew J. Frisch, Rita M. Glavin, Brian P. Maloney, and Sareen K. Armani, in support of Steven Donziger, to Judge Preska (appointed by Kaplan) in criminal contempt case seeking relief from Donziger home detention, Andrew J. Frisch PLLC.

“Roger Waters Tells Chevron’s New CEO to Finally Clean up Ecuador,” video, Amazon Watch.

“Chevron’s SLAPP suit against Ecuadorians: corporate intimidation,” Rex Weyler, Greenpeace, 11 May 2018. The civil RICO case, rulings of Judge Kaplan, and tactics of Chevron, Randy Mastro, and the Gibson-Dunn law firm.

Violence against environmental and human rights activists, Brazilian Cerrado region of industrial soya farms, Greenpeace Report, December 13, 2019.

“Chevron’s Corrupt Legal Practices Called Out by Leading Human Rights and Environmental NGOs,” Paul Paz y Mino, Amazon Watch, June 25, 2019

© Steven Donziger

© Steven Donziger