The passing of the Hauraki Gulf Protection Bill into law this month is a significant milestone for ocean protection. It is an important step on the path to restoring the mauri (life force), habitats, and living species of Tīkapa Moana (the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park). But the Act contains some big failings too.

What is the Hauraki Gulf Marine Protection Act?

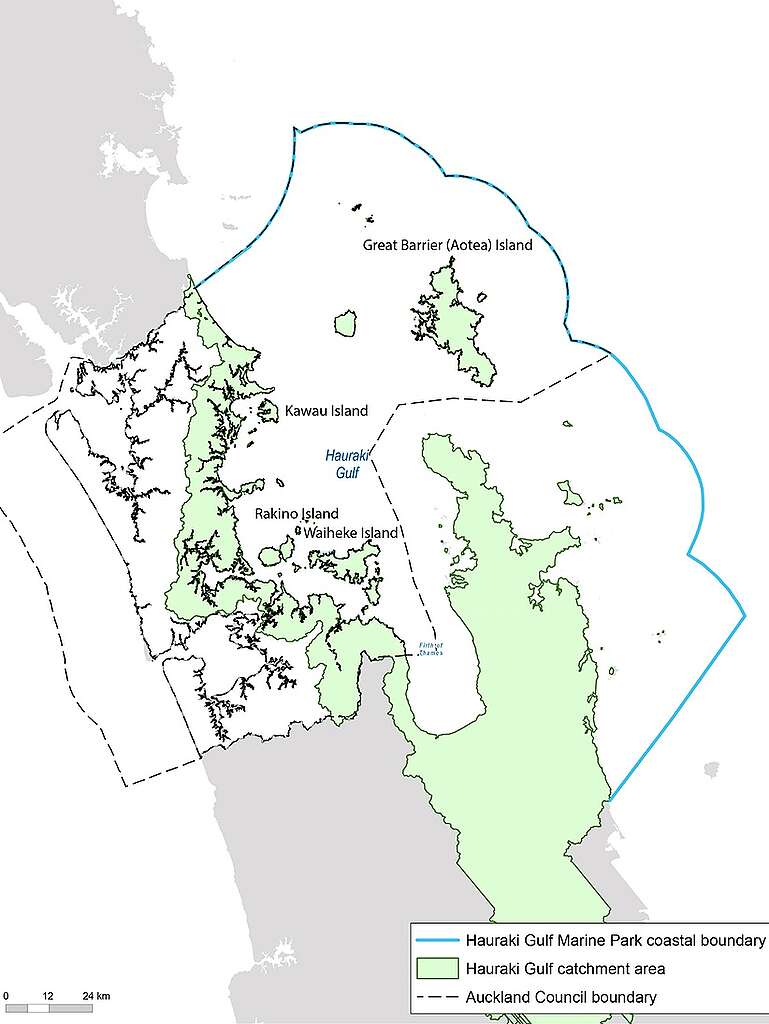

The Hauraki Gulf is New Zealand’s first Marine Park and a national taonga (treasure). It also has historic, cultural and spiritual significance for tangata whenua. It includes more than 50 islands and is home to a diversity of wildlife from seabirds to dolphins, orca, and most of the endangered Bryde’s Whales / Tohorā population.

This Marine Park was created over 20 years ago. Despite that, species are still in decline due to over-exploitation, sediment runoff, pollution and climate change.

The Hauraki Gulf/Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Act is Aotearoa’s most significant increase in marine protection in over a decade. The Act increases the total area that will be given some protection and establishes 19 new marine protected areas. These include high protection areas where most commercial and recreational fishing is prohibited to allow habitats to recover. It also includes Seafloor Protection Areas, which ban fishing methods that affect the seafloor – like bottom trawling and dredging – to protect sensitive ecosystems.

Two existing marine reserves will also be extended.

The Hauraki Gulf Protection Act is the result of decades-long advocacy by local iwi, community, environmental groups and recreational fishers. These groups came together to contribute towards the marine spatial plan SeaChange – Tai Timu Tai Pari.

This plan is a roadmap for the future, aiming to address the decline of the marine environment and restore its vitality.

The Win – the good parts about the Hauraki Gulf Marine Protection Act

The new law increases highly-protected areas. These highly protected areas used to be just 0.3% of the Park but will now make up nearly 6%, offering an opportunity for revitalisation and recovery.

Recovery is desperately needed. Reports say whales and dolphins have almost been wiped out (a catastrophic 97% decline), more than half of all key fish stocks (57%) have disappeared and more two-thirds of seabirds have gone. Crayfish and scallops are functionally extinct in some areas.

By increasing the protection of delicate habitats from over exploitation, we can allow wildlife to recover.

It provides a lifeline for species whose numbers have greatly suffered in recent years. These include sea mammals such as dolphins, Bryde’s Whales, seals, and also rays and sharks.

Through this collaborative, inclusive work, the Gulf is a step closer to healing from a century of exploitation and degradation.

The Caveats – the bad parts of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Protection Act

The new Hauraki Gulf Protection Act is a step forward, but has some significant shortcomings.

Bottom trawling still allowed

Bottom trawling, the most destructive kind of fishing, will still be allowed to continue in the marine park. The new law excludes bottom trawling only from selected areas of the Gulf. This is despite bottom trawling being one of the main drivers of degradation in the marine park.

When bottom trawling nets are dragged along the seafloor they bulldoze precious habitats, warm the climate and destroy marine life and the habitats that they depend on.

People overwhelmingly want more protection of the Gulf. A survey showed 84% of residents around the Gulf want a ban on bottom trawling, and 97% of submitters also supported ending this destructive practice within the entire area of Tīkapa Moana.

Commercial fishing inside High Protection Areas

The most controversial part of the new law is that commercial fishing will be allowed in some High Protection Areas.

This was introduced at the last minute via a widely criticised amendment allowing commercial ring-net fishing to continue in two of the High Protection Areas (Kawau Bay HPA and Rangitoto and Motutapu HPA).

The blatant carve-out is just another example of the government’s disregard for proper democratic process. Yet again, this government overrules advocates, mana whenua, and local government to prioritise the profits of industry.

It is a worrying sign of regulatory capture, a form of corruption of authority that occurs when a political entity is co-opted to serve the interests of an industry, profession, or ideological group.

Permitting commercial fishing in HPAs undermines the meaning of a “high protection area”, setting a dangerous precedent and turning them into fisheries management zones instead.

Redefining protection to suit industry profits

What has happened with this commercial carve out in the Hauraki Gulf is representative of what happens at a global scale.

Marine ecosystems can recover faster and more effectively when ALL destructive activities are stopped. We must be wary of “Paper Parks”, or areas of protection in name only, where harmful activities are still allowed.

The fishing industry actively undermines conservation efforts by lobbying for exemptions. They push for rules that allow them to keep business as usual, or change as little as possible, as slowly as possible. They prioritise private short-term profit over long-term shared vision.

With the entry into force of the new Global Ocean Treaty, which allows the creation of high seas marine sanctuaries, we will see industries – notably commercial fishing – similarly trying to reduce the ambition of protections, and preserve their business as usual.

That’s despite the fact these carveouts significantly reduce the conservation outcomes, spillover effects, and stop it from being the full protection scientists tell us we need to avoid the worst effects of climate and biodiversity collapse.

Full protection is what’s needed in a third of the world’s oceans in order for us to take care of our planet for the future. That’s the bottom line, but industries are going to fight their corner to ensure they lose nothing in the process.

The Missing Pieces – What the Hauraki Gulf Marine Protection Act lacks

The Hauraki Gulf Protection Act falls short of fulfilling our international commitments to ocean protection.

The increased protected area to 6% of the Gulf remains far below the internationally recognized target of 30% marine protection. New Zealand is a signatory to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which requires 30% of marine and coastal areas to be protected by 2030. Achieving 6% protection is still insufficient. And time is getting tight, as the agreed deadline approaches in the horizon.

The bill also faced criticism regarding the recognition of mana whenua, who are key partners in the Gulf’s management. Te Pāti Māori was disappointed that amendments designed to ensure mandatory consultation with mana whenua/iwi were not adopted. Some felt that removing explicit references to whānau and hapū from the legislation, despite assurances of continued iwi engagement, potentially weakens the law.

Exclusion of indigenous voices has unfortunately become a recurring theme for the current governing coalition, ignoring that Te Tiriti is meant to underlie every piece of legislation.

The Power of Collective Action in the Hauraki Gulf

Beyond the ugly spots, the new law is a net positive, and I think it reflects the national situation regarding ocean protection, where communities are coming together to stand up for ocean health.

A group of citizens worked for years, driven by a genuine care for the environment they share with each other and other living beings. They produced a strategy with the vision of a marine park “vibrant with life, its mauri strong, productive, and supporting healthy and prosperous communities”. But then at the last minute the power system interfered on behalf of vested interests.

Yet even with this intervention the government could not completely change the course, set by the collective work of the community.

The lesson is clear: even a government doing its best to benefit industry lobbies cannot counter the power of collective, sustained action.

Locals Taking Action when Government Fails

Meaningful protection is being driven by local communities in the face of central government inaction. An inspiring example is the Waikato Regional Council’s (WRC) proposed Coromandel Bottom Trawl Ban.

The WRC is currently advancing a plan that would effectively close the vast majority of the Coromandel coast to bottom fishing methods such as trawling, Danish seining, and dredging, allowing these destructive practices only along select areas.

The proposal mirrors previous trawl corridor work that the Fisheries Minister decided not to progress. Proving that when the central government sits idle, regional planning processes can become vital mechanisms to protect life in the waters people care most about.

But Fisheries Minister Shane Jones criticised the move, calling the use of regional planning powers to regulate fisheries activity an “abuse of the RMA process.” He also said he was working to limit local government involvement in fisheries management. He argues that fisheries should be the “exclusive business of central government.”

Quite an ironic choice for a government that campaigned on the importance of regional autonomy over local issues.

The reality is that while the Minister sat on the decision on how to restrict bottom trawling in this area, a local governing body took action. They decided to stop the scraping of the seafloor and all creatures living in it. They chose to keep the carbon stored safely in the sediment.

The Fight for the Hauraki Gulf Continues

While we celebrate the new Marine Protection Act, we must heed the example of the WRC and continue to pressure decision-makers at both local and national levels, to prioritise the protection and recovery of Tīkapa Moana, the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park.

Ending all bottom trawling in the Marine Park, and getting more of it protected, remains crucial for restoring wildlife in this precious area. Together we can ensure that the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park will thrive into the future.

Tinkering around the edges will not save the ocean. The time for bold action is now, and heading into next year people around the Gulf and those further afield will be voting with this in mind.

At home and far out to sea, our oceans are being plundered for profit by the fishing industry through bottom trawling. But what is bottom trawling and why is it so destructive to ocean habitats?

Take Action