The images and stories coming out of the the RCMP raids on Wet’suwet’en are disheartening, disturbing and reflect a certain dishonesty about Canadian officials’ self-described commitment to Indigenous rights and reconciliation.

Lands Defenders of the Wet’suwet’en Nation are resisting a $6-billion, 670-kilometre pipeline set to be constructed through their territory. Raids by armed RCMP officers over the past few days have led to the arrest, detainment and denied access of Indigenous Peoples from their lands. The Canadian Association of Journalists and others have condemned police crackdowns on reporters covering the raids.

The complexity of what laws and whose laws apply is something you won’t always see or hear in news reports. Erin Seatter and Gitxsan journalist Jerome Turner (who has been embedded in the Land Defender camps during the raids), put together an amazing explainer piece to help people understand it.

We encourage everyone to read this piece in full. If you can’t, here are some things we learned.

Hereditary chiefs are the title holders of the land.

Under the traditional Wet’suwet’en land system, the hereditary chiefs from each of the five clans (divided into 13 house groups) that make up the Wet’suwet’en Nation have the right to control access over the territory. Trespassing is considered a terrible offence and must be immediately corrected.

“190 kilometres of the proposed route will run through our territory. It threatens our water, our salmon, and our rights, our title, our jurisdiction,” Hereditary Chief Na’Moks of the Tsayu Clan told APTN.

What about band councils?

Band councils (such as those Coastal GasLink boasts have signed agreements) have control over reserve land which is only a small portion of Wet’suwet’en territory — and the majority of reserve land, the pipeline wouldn’t pass through. Band council authority comes from colonial law: the Indian Act. However, the vast majority of land in B.C. is unceded. This means it was never legally signed, ceded or given away to colonial powers. When it comes to the 22,000 square kilometres of unceded Wet’suwet’en land, the hereditary chiefs hold land title.

A 1997 Supreme Court of Canada ruling affirmed Wet’suwet’en land rights, including that the hereditary chiefs are the title holders.

A court case brought by the houses (not just band councils) of the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan resulted in a hugely significant decision. Over more than 300 days, Elders and hereditary chiefs presented evidence, oral histories and ceremonial songs. The decision, Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, confirmed the validity of oral histories as evidence and recognized the chiefs’ hereditary governance and Indigenous Nations’ land interests. On the downside, the court did not affirm where the land title of the Wet’suwet’en and Gitxsan applied (and the Nations did not have the resources to continue the case).

Without the support of hereditary chiefs, pushing through the Coastal GasLink pipeline violates Indigenous rights.

In 2019, B.C. passed provincial legislation to implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Under this piece of international human rights law, Indigenous Peoples have the rights to “free, prior, and informed consent” (FPIC) on any developments on their lands.

Article 10 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states: “Indigenous peoples shall not be forcibly removed from their lands or territories. No relocation shall take place without the free, prior and informed consent of the Indigenous Peoples concerned and after agreement on just and fair compensation and, where possible, with the option of return”. The province has also committed to reconciliation with the Wet’suwet’en.

At the same time, the B.C. government supports the construction of a massive natural gas export facility on the coast. This facility, LNG Canada, depends on the Coastal GasLink pipeline, which the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs are resisting. Without consent, the pipeline cannot go forward without violating Indigenous rights and Wet’suwet’en law.

So, upholding rule of law isn’t as simple as enforcing injunctions (which also appear to be biased against Indigenous Peoples).

The RCMP have said that enforcing the injunction granted to Coastal GasLink by the B.C. Supreme Court is not optional. Clearly, it’s not that simple. By focusing only on the injunction, the courts, RCMP, B.C. Premier John Horgan and Prime Minister Trudeau (since the state is the duty bearer for human rights) are ignoring reconciliation and Indigenous rights responsibilities.

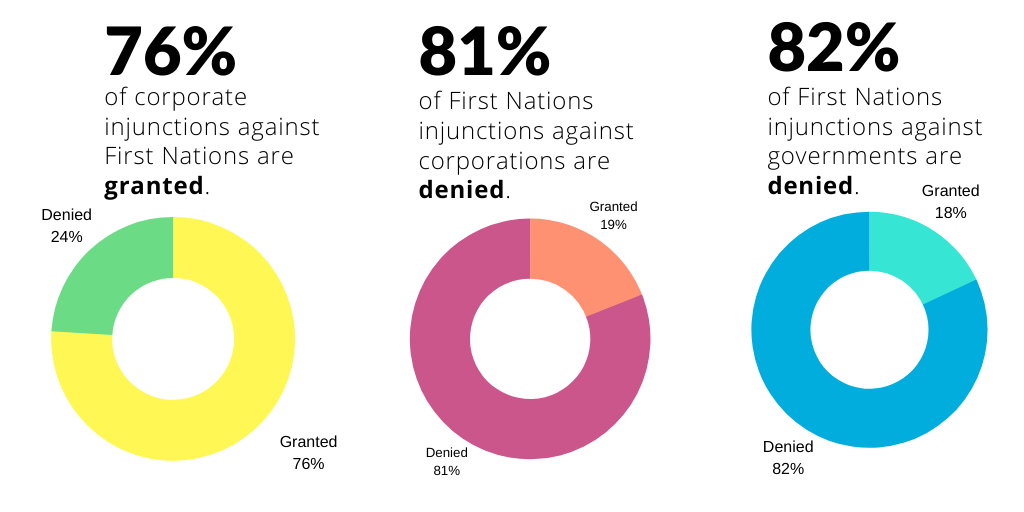

What’s more, as highlighted in the Ricochet article we mentioned, the Yellowhead Institute has found that injunction battles are weighted against Indigenous Peoples.

Is there a way forward?

Respect for Indigenous law and human rights must be at the core of any way forward. Article 27 of UNDRIP calls on countries to cooperate with Indigenous Peoples to create an impartial and transparent processes to adjudicate Indigenous land, territorial and resources rights (including those that are traditionally held).

“That tribunal would use whatever the Indigenous system would be, so here it would be the Wet’suwet’en system, plus the Canadian system. They would both be used by this tribunal to work out some kind of resolution, “ Gordon Christie, a University of British Columbia law professor, told Ricochet.

Discussion

They have every opportunity to elect their hereditary chiefs but dont. I have a hard time believing Greenpeace recognizes the sons and daughters of kings and queens as legitimate authority but are doing just that when it is convenient for them. Green peace still holds on to the antiquated and racist view of the 'painted Indian'. I have a hard time going against the govts chosen to lead by the wet'suwet'en people. I fully support initiatives to break free of fossil fuels but as has been pointed out this is for the wet'suwet'en people to decide not me or Greenpeace.