Early in the morning of 26 April 1986, the fourth reactor exploded at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine. Thirty-four years later, Chornobyl radioactivity is still circulating. The long-lived radionuclides released by the accident mean the disaster continues decades on.

The wildfires started on 3 April due to abnormally hot, dry and windy weather. They are now the biggest fires ever recorded in the Chornobyl exclusion zone. This, one of the largest wildlife areas in Europe, will take years to recover.

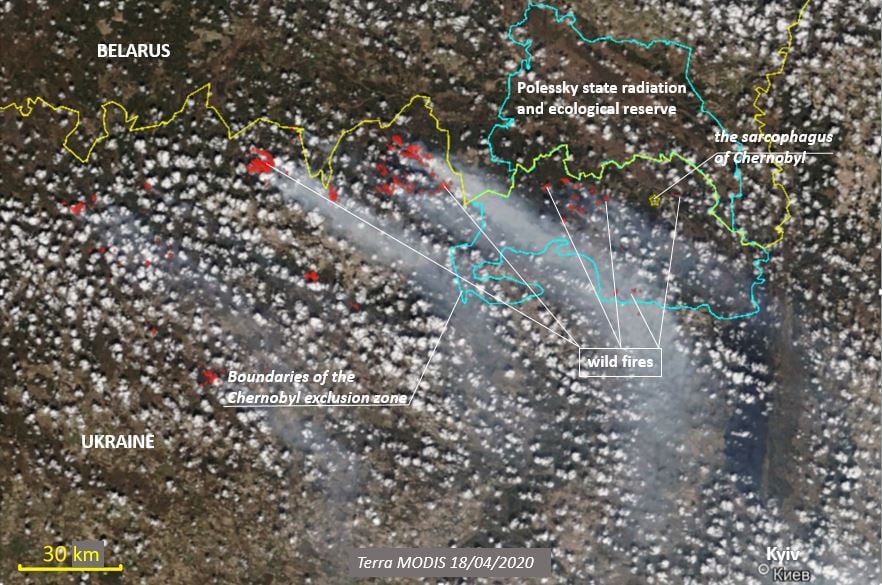

With the Greenpeace Russia forest team and global mapping hub, I have been following these wildfires since they began. Satellite images show that an estimated 57,000 hectares of the Cherbobyl exclusion zone has burned so far. That is 22% of the total area of the exclusion zone.

As I write this, three weeks after the start of the fires, at least three of the largest fires continue burning. One of them is located close to the site of the old nuclear power plant, only 4km away from the sarcophagus. Hundreds of ill-equipped firefighters and foresters are currently trying to get the fires in northern Ukraine under control.

The wind has carried some of the smoke over more populated areas. On 16 April, plumes of smoke caused smog in the Ukrainian capital Kyiv, 250km away, and although they did not exceed norms, higher levels of radioactivity than usual were detected. The smoke and ash have also crossed borders: the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority registered a small increase of caesium-137 concentrations in the air in Norway.

Increased activity of Caesium-137 and other radionuclides in the air can lead to a rise in levels of cancer. Whoever can smell the fire could also inhale these radioactive substances.

So yes, potentially dangerous radionuclides are travelling with the fire haze. This is due to the fact that since 1986, the forests have accumulated radioactivity, mostly concentrated in the wood and upper soil layers. This is why, in the contaminated areas, the village dwellers living nearby are deprived of their right to use the forest for the next 300 years. The “exclusion zone” surrounding the Chornobyl nuclear power plant is still – 34 years later – heavily contaminated with caesium-137, strontium-90, americium-241, plutonium-238 and plutonium-239. Plutonium particles are the most toxic ones: they are estimated to be around 250 times more harmful than caesium-137.

Fire releases these particles into the air where wind can transport them over long distances, eventually expanding the boundaries of radioactive contamination. There is currently no data on the amount of nuclear material that has been released into the atmosphere because of these fires, so we don’t know how far they have travelled. It is possible that most of the radionuclides will settle within the exclusion zone and nearest area, as these are heavy particles.

We know from previous (smaller) fires that happened in the area in 2015 that scientists found a release of 10.9 TBq caesium-137, 1.5 TBq of strontium-90, 7.8 GBq of plutonium-238 , 6.3 GBq of plutonium-239, 9.4 GBq of plutonium-239 and 29.7 GBq americium-241. It is clear that the numbers will be higher this year.

Close to the fires, firefighters and local people are exposed to risks from both smoke inhalation and radiation. Cities like Kyiv are exposed to the health impact of inhaling smoke in the short term and in the longer term, risk internal irradiation through contaminated berries, mushrooms and milk bought on the local markets. No-one is immune from radioactive products getting into their homes.

The consequences of Chornobyl are still here. People are still at risk, exposed and fighting on the frontlines. Forest fires in contaminated areas are a big problem for Ukraine, Belarus and Russia, where five million people still live in contaminated areas according to official data. These fires happen almost every year.

The Greenpeace Russia firefighting squad has helped several times to extinguish the fires on contaminated territories. This year, our firefighters have not been able to go on site to help due to the coronavirus pandemic.

These forest fires are burdening an emergency ministry already in the midst of a health crisis. This goes to show that other emergencies can be exacerbated by nuclear-related incidents – a situation that we have little or no control over.

Nuclear-related risks themselves are exacerbated by a lack of transparency: at the beginning of the fires, the first official accounts minimised the areas on fire by about 600 times. Secrecy was one of the reasons why the Chornobyl disaster was so severe in 1986: it was later confirmed in court that even the director of the Chornobyl power plant was not made aware of a disaster at the Leningrad nuclear power plant in 1975 that would have given clues to what happened in reactor 4.

Chornobyl will continue to pose a threat for many generations to come.

Rashid Alimov is a nuclear campaigner at Greenpeace Russia