Record-breaking frosty temperatures, ice and heavy snowfalls have gripped huge areas of the Northern Hemisphere this winter. For example, cities in East Asia such as Beijing and Seoul shivered in two of the coldest snaps either had experienced for decades, over in Europe. Spain experienced record low temperatures of -25 Celsius and much of the Netherlands froze over, while snowstorms smothered the northeastern US with more than half a metre of snow.

This extreme weather, impacting more than a billion people worldwide, is yet another sign of the climate crisis despite the fact it looks like global cooling rather than global warming. How so? Well, it’s got a lot to do with a warming Arctic prompting the collapse of the polar vortex. Does that all sound a bit complicated? Never fear, we will explain exactly what a polar vortex is, how it’s affecting our weather and linked to the climate crisis, and what we can do about it.

So, what’s a polar vortex then?

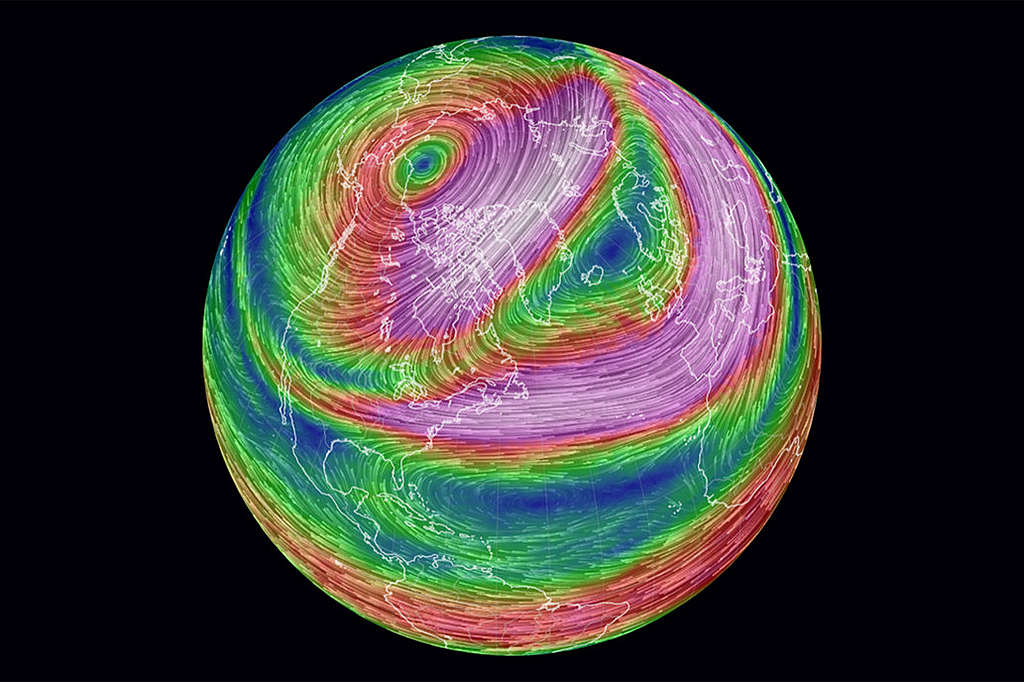

The polar vortex is a giant swirling ring of cold air that rotates high up in the atmosphere at both the North and the South Poles, but for this blog, we will focus on the polar vortex in the North Pole. It always exists near the poles, but weakens in summer and strengthens in winter. Being cut off from the sun’s warmth in the Arctic makes it very much colder than the equator, which stays hot year-round.

The atmosphere tries to balance that extreme temperature difference by setting the cold air in the North Pole spinning – and that’s the polar vortex. This giant spiral of freezing winds is in the stratosphere, at least 16km above the Earth’s surface, so it’s too high to directly affect our weather, but it does have an indirect impact. When it’s rotating nicely, all that cold air stays in the vortex, but when the vortex gets wobbly, that cold air escapes southward and starts a chain reaction that sends the temperature dropping.

What makes the polar vortex go ‘wobbly’?

It’s a bit hard to unravel, but meteorologists think it’s got something to do with a sudden temperature spike in the air in the stratosphere above the North Pole. A rapid and extreme rise in temperature there tips the swirling polar vortex off its axis, and it starts to wobble and extends much further south than it usually does. During this wobbling, the cold air – also known as jet stream – is also pushed southwards.

Early this year, weakened polar vortex brought record-breaking cold waves across East Asia. Now the vortex warped into two “legs” that protruded into North America and Europe. Those legs caused the frigid air closer to the earth’s surface (which is what directly affects our weather) to bulge southwards, forcing cold front down across much of Europe and North America this winter.

OK. So what’s climate change got to do with it?

There is a lot of evidence that the climate crisis is one of the main reasons that the polar vortex got pushed off course, causing an unusually harsh winter. We know that the Arctic is warming at a speed double that of the rest of the world. This has shrunk glaciers and melted away a significant amount of sea ice in the area. Scientists think it’s possible that this has made the polar vortex more prone to wobbling. One theory is that with less sea ice to reflect solar radiation, Arctic waters are getting warmer, causing clouds of warmer air that create ripples that dislodge the polar vortex.

There’s a lot more going on than this, but what is certain is that the polar vortex going wobbly has been happening much more frequently over the past decade or so. And that means that unusually harsh and dangerous winters, something which used to be a rare event, are now becoming much more common like other climate crisis-linked extreme weather events.

What’s so bad about a bit of cold though?

Severe cold weather is a huge and often tragic problem. People die from the cold or from accidents caused by extreme weather such as car pile-ups. More than a dozen people were left dead from record snowfalls in Japan, while in Spain, a freezing blizzard left four people dead from hypothermia, flooding and suffocation from a snow pile up. Snowstorms paralyse transportation systems including road, rail and air; freezing winters lead to crop failures and livestock deaths that disrupt food production; and extreme inclement weather can cut off energy supplies causing blackouts and hardship. Storms at sea can cause loss of life and economic damages. This is not just a bit of cold weather – extreme weather events are almost always dangerous.

In the United States, Texas is experiencing record cold temperatures and the failure of its fossil-fueled electric power grid. The blast of frigid weather in February left millions of Texans without power or the ability to heat their homes for multiple days. Conservative politicians who have taken millions of dollars from fossil fuel interests throughout their careers were quick to blame wind turbines and Green New Deal policies that the state hasn’t even implemented yet. The reality is that frozen instruments at gas, coal, and nuclear plants are largely to blame. What is happening in Texas makes clear that fossil fuels aren’t just polluting, they’re unstable.

The polar vortex is also wreaking havoc across areas of northern Mexico, with the dangers of the cold exacerbated by the failures of the fossil-fueled electric power grid in the US. Given the impact on electricity generation in Mexico, the Federal Electricity Commission requested the National Center for Energy Control to declare an Operational State of Alert.

What can we do about it?

We can go to the heart of the problem and take immediate actions to mitigate the climate crisis. We need urgent policy shifts to massively transform our economies to carbon-neutral ones as soon as possible.

Basically, the only way to truly tackle extreme weather events is to tackle the climate emergency.

That means phase out ALL fossil fuels (don’t even mention the word, coal), 100% renewable energy everywhere and for everything, and smart energy saving and energy efficiency. We can all do our part, and that’s extremely important. Many of you are already taking action by opting for public transport, biking or walking, switching to a renewable energy provider, and being smart about energy use. But ultimately governments and big corporations must ultimately lead the way to get to the heart of the problem.

And they must start leading now.

And that’s where East Asia comes into play

Last year, China, Japan and Korea committed to going carbon neutral by 2050 or 2060. They demonstrated real leadership. But promises are just words, and what we need now is real action. These three countries – collectively responsible for one-third of all global carbon emissions in 2018 – must now publish long-term, concrete plans to meet these announced targets and a detailed timeline for how they will move to 100% renewable energy.

Greenpeace East Asia is making this campaign an absolute priority this year. We will take your voice to the halls of power, the boardrooms of shareholder meetings, and everywhere and anywhere we can to propel this vibrant and fast-moving corner of the world – to take action, and make real and positive changes for our climate. Will you join us?

Dinah Gardner is a freelance writer.