In 1971, a small group of activists set sail to the Amchitka island off Alaska to try and stop a US nuclear weapons test. The money for the mission was raised with a concert, their old fishing boat was called “The Greenpeace”. This is where our story begins.

“Why not sail a boat up there and confront the bomb?”

It was a fancy, at first. Marie Bohlen casually expressed the idea over coffee one morning. But the people around her – a loose alliance of Quakers, pacifists, ecologists, journalists and hippies – weren’t known for shrugging off the really big ideas.

A few weeks later, the Don’t Make a Wave Committee – as the group was still called then – had a plan. “If the Americans want to go ahead with the test,” Marie’s husband Jim said, “they’ll have to tow us out.”

Leaving one of those heady first meetings, Irving Stowe flashed the peace sign – as was his custom – and said “Peace”. On that occasion, the usually rather quiet Canadian ecologist Bill Darnell made the off-hand reply: “Make it a green peace.”

When the words didn’t fit onto buttons for the group’s first fundraiser, they were simply merged: Green Peace became Greenpeace.

The concert

We had our name, but it was soon clear that selling 25-cent buttons wouldn’t bring in the cash needed to buy a boat. Someone had the idea to put up a rock concert.

A few phone calls later, Joni Mitchell said she would be playing. Chilliwack and Phil Ochs confirmed, before Joni called again to say she would bring a special guest: James Taylor. None of them wanted any money for the night.

“The concert was a sell-out, the biggest counter-culture event of the year,” Rex Weyler recalls in his Greenpeace biography. The sixteen thousand that filled Vancouver’s Pacific Coliseum left the concert entranced.

Afterwards, attendance at the meeting swelled, the money started to pour in. By the end of October, the group had raised more than $23,000. Greenpeace was ready to go.

The voyage

Yet, the voyage was a disaster. The boat left the harbour at dusk on 15 September 1971, but internal tensions soon flared up.

“We never quite managed to go in the direction we wanted to go, or be in the place we wanted to be. And we fought bitterly among ourselves about it. Everything we did or said got sucked into an overwhelming power struggle.”

“Here we were, supposedly saving the world through our moral example, emulating the Quakers, no less, when in reality we spent most of our time at each other’s throats, egos clashing, the group fatally divided from start to finish.”

Even worse, “The Greenpeace” was intercepted by the US navy, before it even got close to the Amchitka testing site.

Failure looks different, however. The Amchitka voyage sparked a flurry of public interest. The media went wild about the small group of activist who had sailed off in the face of great adversity – the first “media mindbomb”, as Bob Hunter conceived of those early Greenpeace actions, had been launched.

The beginning of a much bigger story

“As it turned out, all my angst was unnecessary,” he later wrote. “Time has proven my post-trip despair to be utterly mistaken. The trip was a success beyond anybody’s wildest dreams.”

The nuclear bomb the group had come to stop went off, but the tests planned for after that were cancelled. Five months after the group’s mission, the US stopped the entire Amchitka nuclear test programme. The island was later declared a bird sanctuary.

“Whatever history decides about the big picture, the legacy of the voyage itself is not just a bunch of guys in a fishing boat, but the Greenpeace the entire world has come to love and hate.”

Today, Greenpeace is the world’s most visible environmental organisation, with offices in more than 55 countries and over 2.9 million members worldwide. Amchitka, it has turned out, was only the beginning of what would come to be a much bigger story.

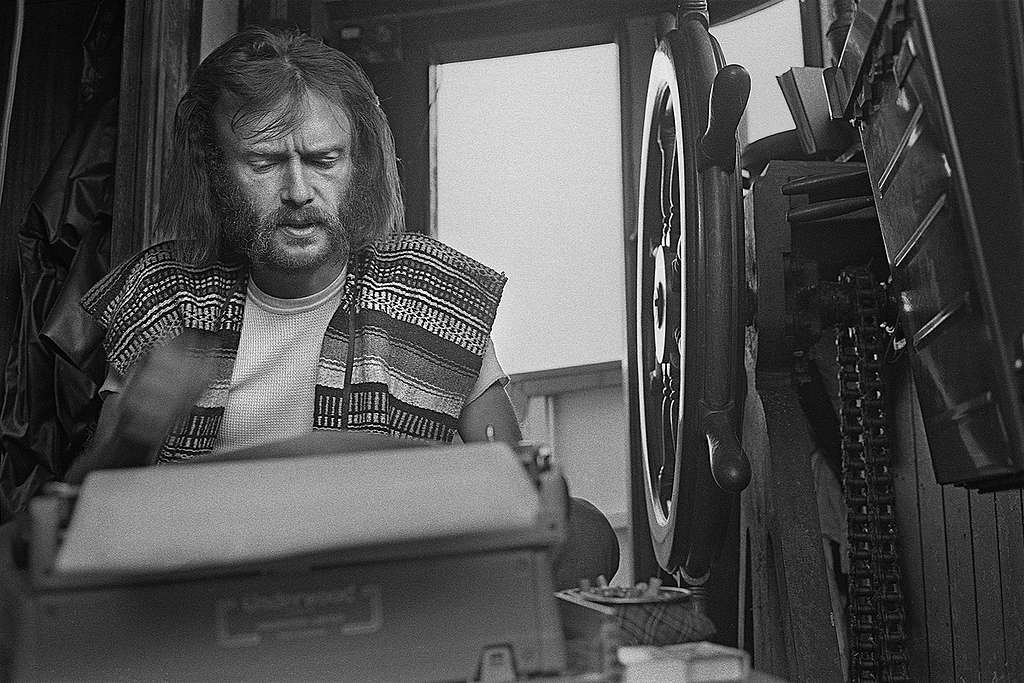

Bob Hunter’s account

Bob Hunter sailed aboard the first Greenpeace voyage in 1971 to Amchitka in the Aleutian Islands to try and stop a U.S. nuclear weapons test. When they were halfway to their destination, Richard Nixon announced a month’s delay of the test. Most of the crew were running out of money or vacation time, and an acrimonious debate broke out about whether to continue or turn back. This is Bob’s story about what happened.

When I got back from the expedition to Amchitka and sat down to write a book about it, I was convinced we had lost, and I was angry. The best chance ever to actually interfere with nuclear testing, and we had blown it through sheer stupidity – and a failure of nerve, to put it kindly. Cop-out on the Way to Amchitka was the title that loomed in my mind. And my personal failure of will was a big factor in that cop-out. Worse, I was afraid that I’d subconsciously thrown the fight to carry on with the voyage. I’d have to live with that until I died or the world blew up, whichever happened first.

I was also facing the most serious writing dilemma of my life. Since childhood, when I had started writing science fiction in my school scribblers, I had been looking for “experience”. Like all intense young writers, I had plenty to say, but rather little context in which to present my thoughts. I’d read a bit, but there had been no plagues or crusades or recent wars on home ground. Even when the Great Red River Flood hit in 1950, my family was evacuated before the dikes broke. Real-life adventure had been hard to come by in working-class south Winnipeg after the war, a period during which Canada was at its dullest, if you can imagine. Such adventures as I’d managed to experience when I was growing up had been of the ordinary romantic or travel or childhood close-call variety. I had done some solo camping in the boreal forest and some hitchhiking in the western Canada and Europe, had got married and fathered two children, had embarked on an interesting career in journalism and published three books, but until that fateful voyage in the fall of 1971, nothing had happened to me that leaped out as being absolutely essential to write about, if only for my own understanding of life. And now that it had, I was obliged not to write about it – for the sake of the cause.

The problem was that I’d joined. What exactly I’d joined was not yet clear – it was still being defined – but I had definitely stopped being on the outside looking in and was instead on the inside looking out. I’d started out as a newspaper columnist, the ultimate Ishmaelian outsider, accustomed to being responsible for nothing except the authenticity of my insights and words. “Tell it like it is” was the creed of the counterculture scribe, and my personal mantra. Suddenly I found myself in the inner circle of a nascent political organization, with a bit of potential power in my hand, which at the time seemed like the power to change the course of history. All that had to happen was for the MV Phyllis Cormack, aka Greenpeace, to make it to Amchitka Island and park there under the nose of a nuclear test bomb code-named Cannikin. How much simpler could it be?

Yet everything got fucked up. We never quite managed to go in the direction we wanted to go, or be in the place we wanted to be. And we fought bitterly among ourselves about it. Everything we did or said got sucked into an overwhelming power struggle. Here we were, supposedly saving the world through our moral example, emulating the Quakers, no less, when in reality we spent most of our time at each other’s throats, egos clashing, the group fatally divided from start to finish. As every writer since Homer could tell you, this was the story: the conflict within. But having agreed, early in the game, to the Unity Rule – something like: I Pledge to Stay On-Side With the Group No Matter What, which had seemed like a bold leap into solidarity with The Movement at the time – I had effectively gagged myself as a reporter and historian. It was a trade-off: but I bought into it, so I couldn’t complain. I’d get to be part of the consensus – my own skinny hand on the wheel of decision-making over the course of the Greenpeace, and therefore destiny – but like any other politician, I’d have to agree not to disagree in public. I disagreed, as it turned out, with just about everything that was done, but had to keep my mouth shut. How, therefore, to write a book? An authorized book, which followed the party line yet still told the awful truth – that we had screwed up.

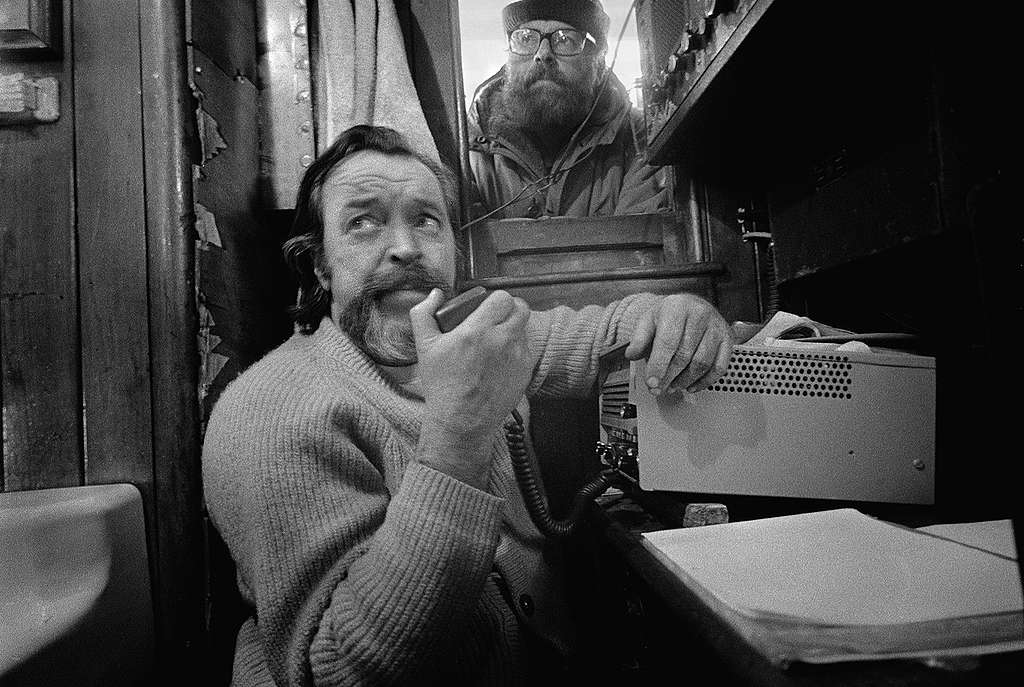

Three decades later, his grey beard turned white, Jim Bohlen confided to me over a drink that he had been giving the sailing orders to our captain in secret throughout the voyage. As the guy signing the cheques and as the chairman of the Don’t Make a Wave Committee, which had chartered the boat, Bohlen had the legal authority to do that, but rather than say that he was the boss, and that the Greenpeace and the protest action were therefore being run as an old-fashioned hierarchical power structure, he played games to keep us radical young crewmen under control. One of them was the promise that the ship would be run by consensus – each of us would have the power of veto. This was considered the ultimate hip form of sharing power at the time, and I, for one, respected it.

But it was all a sham. Decisions were indeed made – Bohlen made them. And he made them after the rest of us had gone back to our bunks. At the time I wrote my manuscript, immediately after the voyage, I had no idea what Bohlen had been up to behind the scenes. On any given day the actual movements of the boat, as opposed to the direction we’d agreed to at our meeting the night before, remained a mystery to me. Bohlen had us completely flummoxed. I salute him now for his cunning and maturity and prudence. We probably would have died if he hadn’t assumed control. But back then, I plotted and connived to overthrow him as leader because he was “chickening out”. Ben Metcalfe, Bohlen’s co-conspirator in the plot to bring us home alive, the other mature war veteran on board, and the mastermind of the media campaign, saw no reason to put us at risk of committing mass suicide, and I sneered at him for having “lost it”. But this guy had fought in the Desert War against Rommel, had resisted raf orders to bomb Gandhi’s followers, and was so far ahead of me in terms of that elusive stuff called experience that there was never any doubt that in matters of life or death he would outmanoeuvre the mutinous but naïve youth faction. He was an old rogue survivor. A genius, I now realize. In the end, I studied at his feet.

The man who ultimately determined the fate of that first Greenpeace trip was John C. Cormack, the captain and owner, who had accepted the job of sailing his fishing boat into a nuclear test zone only out of economic desperation, a fact that never got talked about much. In hindsight it is interesting to remember what Cormack did and did not do at the critical moment. He saved his boat and us along with it. And we all saved face, at least enough to go home.

The key moment of the trip came a day before we limped back into Vancouver. As we all sat slumped in the galley, burned out, Bohlen announced that he was going to shut down the Don’t Make a Wave Committee as soon as he got the chance. It was an ad hoc group and it had done its thing. Don’t do that, I told him. Why waste all this hard-earned media capital? Fold the committee, sure, but reconstitute it as the Greenpeace Foundation. That was my main contribution, yet the moment did not find its way into my manuscript. It was an element of hope for a future revolution, and I was not hopeful as I bobbed in the harbour at Steveston, heartsick and overmedicated, writing the story of our failure. In the end I told the truth as I saw it, supposedly as it was, never mind loyalty to the cause.

As it turned out, all my angst was unnecessary. Time has proven my post-trip despair to be utterly mistaken. The trip was a success beyond anybody’s wildest dreams. That bomb went off, but the bombs planned for after that did not. The nuclear test program at Amchitka was cancelled five months after our mission, and some scholars argue that this was the beginning of the end of the Cold War. Whatever history decides about the big picture, the legacy of the voyage itself is not just a bunch of guys in a fishing boat, but the Greenpeace the entire world has come to love and hate.

Excerpt from “The Greenpeace to Amchitka”

By Bob Hunter Published by Arsenal Pulp Press, Canada

ISBN Number: 1-55152-178-4

Reproduced with kind permission JUNE 2004