A photographer looks back at Greenpeace’s early years

From 1974 to 1982, I served as photographer on Greenpeace campaigns. Here are a dozen photographs from those years and some memories that they evoke:

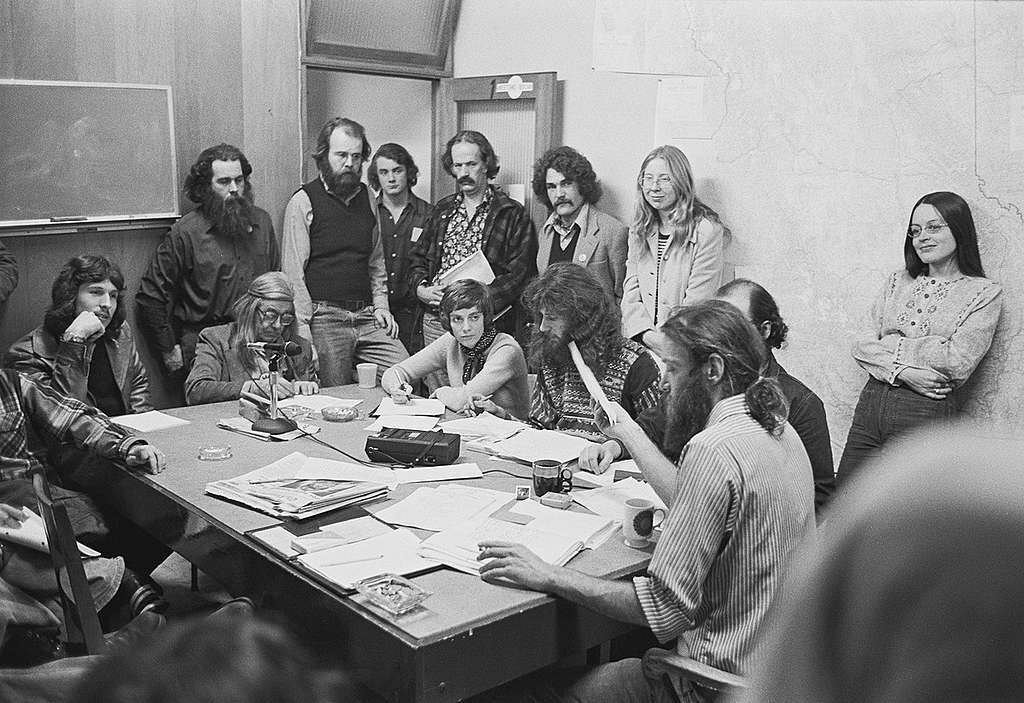

The first public Greenpeace office opened in 1975 on 4th Avenue in Vancouver

The very first Greenpeace office was in the home of Dorothy and Irving Stowe in Vancouver. We used to meet at the Unitarian Church, in our kitchens, in coffee shops, and in pubs. In 1975, leading up to the first whale campaign, we shared this small office space with the only other ecology organization in Vancouver, the Society for the Prevention of Environmental Collapse (SPEC). Our tiny adjoining office, run by Bobbi Hunter, consisted of one telephone, a bulletin board, and a long wooden slab for a desk. We often met at the pub across the street, upstairs by an open window, and when we got calls in the office, Bobbi would shout across the street, and the requested party would run across the street to the phone.

Here, Bob Hunter, Greenpeace president, sits at the head of the table in the shared meeting room with papers in hand. Bree Drummond, who had climbed into cottonwood trees to protect them from loggers, leans against the wall. Leigh Wilks, a nurse at Vancouver Hospital, is taking notes, sitting beside Rod Marining, one of Vancouver’s ecology visionaries, and media liaison during the whale campaigns. There were no salaries. Everyone was a volunteer.

A sperm whale lies dying under the bow of a Russian harpoon ship, 1975

A black and white version of this iconic image from the 1975 whale campaign appeared in newspapers around the world. When we planned the whale campaign, one of our goals was to replace the old Moby Dick’ image of whaling — brave little men in tiny boats pursuing a ferocious leviathan — with the reality of modern whaling — giant steel ships with exploding harpoons decimating vulnerable families of cetaceans. This image helped flip that perception, as we can visually see and viscerally feel the deadly imbalance of power.

This photograph was taken on the first day that we encountered the Russian whalers, June 27, 1975, over the Mendocino Ridge sea mounts, 50 miles off the coast of California. We worked so feverishly that day, that I did not realize until later that evening how heartbroken and traumatized I felt after witnessing the carnage.

Taeko Miwa and Mel Gregory in the wheelhouse of the Phyllis Cormack, the first Greenpeace ship, 1975

Taeko, from Japan, was possibly the most experienced environmental activist on the crew of the 1975 whale campaign. She had worked with victims of mercury poisoning in Minamata, Japan, where over 2,000 people had died and thousands more suffered life-long afflictions caused by industrial wastewater from the Chisso Corporation chemical plant. She had led a clean-air campaign in Tokyo, and a protest against the new Tokyo airport that devastated a rural community. Mel was a Vancouver musician, who had a deep affinity with animals. He would protect spiders from being killed by others, even by strangers, and he had a pet iguana named Fido. During this voyage, he experimented with playing music to whales through under-water speakers, while recording their response. Mel brought a “Dream Book” onto the ship for crew to record their dreams, which led to many fascinating discussions and to a historic dream/poem in the book from renowned poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

Bobbi Hunter and Russian harpoon boat, 1976

Between 1974 and 1978, Bobbi was the Greenpeace Foundation chief fundraiser and office manager. In 1976, she served on the whale campaign crew. This was the first time that we actually stopped a harpoon boat, dead in the water, ending its hunt. During the 1970s, the office teams and campaign teams were interchangeable. We believed that the activists should do a variety of jobs, in the office, with the public, and on campaigns. We made every effort to make sure that willing office staff had opportunities to serve on the front lines of campaigns. Bobbi was on the marine radio almost every day, with the staff in Vancouver, keeping track of budgets and campaign logistics.

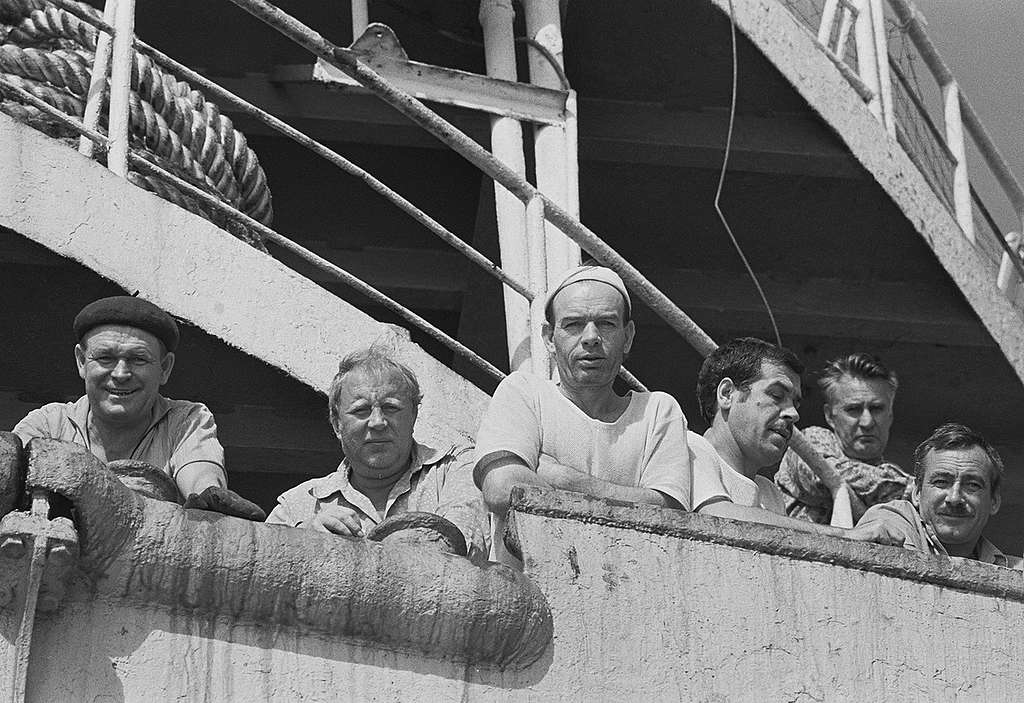

Russian whaling crew on board the Dalnyi Vostok, 1975

We developed friendly relations with most of the whaling crews (not necessarily with the officers). The first time we got close enough in a Zodiac to speak with them, someone asked us in English: “Do you have LSD?” We weren’t able to satisfy this request, but we returned to our ship and brought back bottles of rum and whale pins, which they were pleased to receive.

I realized during various ecology campaigns that every ecological issue we addressed had an impact on someone’s job or livelihood. Clearly, part of the ecological transition of society would require efforts to support those employed in harmful industrial or military processes. This challenge remains with us to this day. Solving our ecological crisis probably means a substantial revision of our entire economic system.

Photographers Matt Herron and Kazumi Tanaka capture the process of transferring dead whales from the harpoon ships to the factory ship Dalnyi Vostok, in the Pacific Ocean, 1976

The whales were carved up on the factory ship deck, and a pipe protruding from the hull ran continually with blood. Sharks followed the factory ship, and the stench from the floating slaughterhouse made us all nauseous.

Taking a photograph from a moving Zodiac, even in a mildly choppy sea, is extremely difficult, and we struggled with this at first. We learned in 1975 that the most effective method was to stand in the bow, with a rope from the prow around one’s waist. With this method, the photographer could lean back, legs and rope creating a tripod, and remain stable with two hands free.

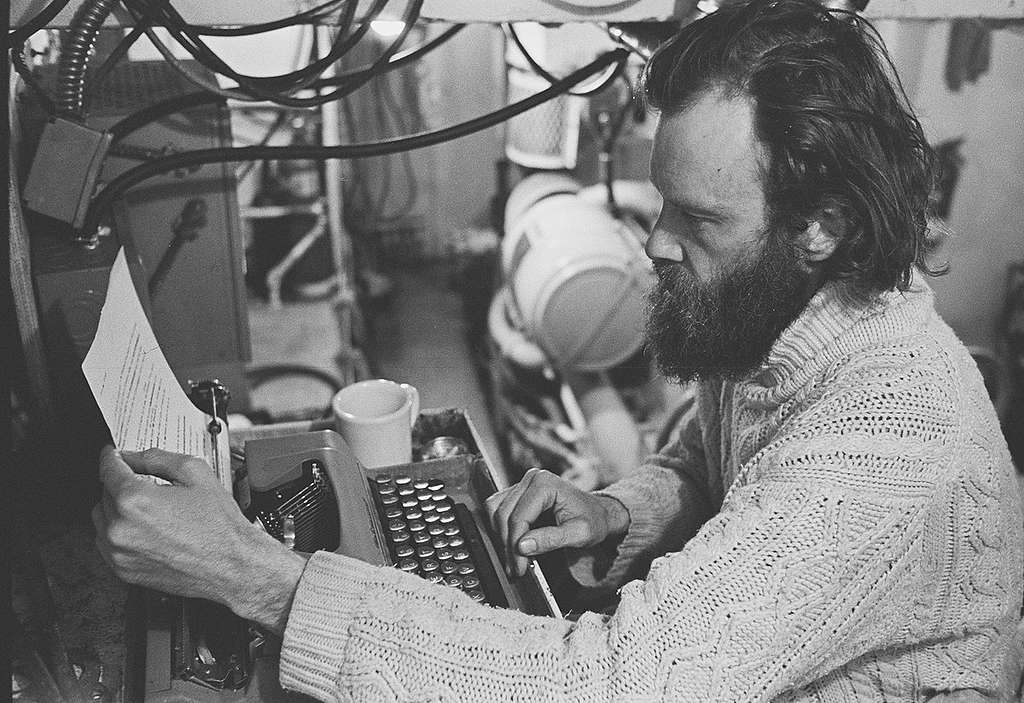

Bob Hunter typing a media release at his engine-room desk, 1976

This photograph was taken on the James Bay, the Canadian minesweeper used for the 1976 and 1977 whale campaigns. There was no internet, and we possessed no means to distribute news and photographs from the ships during this time, except by marine radio. Hunter and I would call our respective newspapers on the radio, and read stories to our editors, who would record and transcribe them. To send photographs, we had to reach land, process the film, and send photographs on the wire services.

Hunter was a splendid writer and a media prodigy. He was a student of media analyst Marshall McLuhan, who predicted the internet in the 1960s and showed how communications technologies affect human cognition and therefore influence social organization. Hunter’s now-famous “mind-bomb” theory of social change, suggested that the fastest way to change society involved launching images and stories — “mind bombs” — that would “explode in people’s heads all over the planet.” Greenpeace, he suggested, should let others sort out the details; our goal was to infect the entire human family with an idea: We are relatives with all living beings, we are children of our Mother Earth, and we have a responsibility to care for her.

Bree Drummond (later Marining), in the engine room of the James Bay, 1976

Bree was a seasoned activist, had saved a stand of cottonwood trees in Vancouver, helped organize the 1976 harp seal campaign, and coordinated the engine room watch schedule during the 1976 whale campaign. Engine room watch is a serious job on any ship. It took about an hour, twice a day, to check all the oil pressure valves, fuel pumps, coolant and temperature gauges, to check for deterioration or cracks, to operate the bilge pump, and keep the engine room clean. One of the greatest threats on a ship is an engine room fire, which can ignite from engine sparks striking pools of untended oil or fuel.

The popular media images from Greenpeace campaigns highlight activists engaged in visible confrontation with the opposition. However, for every activist climbing a tower or blockading a whaling ship, hundreds of volunteers perform the less visible, less glamorous jobs that are essential for any successful campaign.

Jerry Garcia and friends play a benefit concert on the Greenpeace ship James Bay, August 12, 1977, at Pier 31 in San Francisco

Six days earlier, Mel Gregory, Caroline Keddy, and I had traveled across the bay to the Keystone Club in Berkeley and talked our way into the backstage area, where we met with Garcia, who agreed to do the benefit. In the next five days, we secured the permits, drove 50 miles north of San Francisco to meet with a concert producer, created a perimeter around the pier, built the stage and speaker platforms, built a sound technician’s hut, decorated the ship itself as a backstage area, put tickets on sale, visited radio stations to promote the show, and sold out all the tickets. We were always broke in those days, raising money as we traveled on campaigns. The show raised $20,000, enough for us to refuel and provision the ship and go back out after the whaling fleets.

Garcia was joined by John Kahn on bass, Ron Tutt on drums, Keith Godchaux on keyboards, and Donna Jean Godchaux and Maria Muldaur singing vocals with Garcia. Members of the Jefferson Airplane band can be seen in the background, on the ship.

Bob Hunter and John Cormack, 1975

Without Captain John Cormack, there probably is no Greenpeace today. He agreed to take the original 1971 crew to the Aleutian Islands nuclear test site in his 66-foot fishing boat, and in 1975 and 1976 he agreed to take his boat on the whale campaigns. Cormack was an ex-wrestler, 40 years a fisherman, strong and self-assured, but with a modest bearing. He did not drink alcohol, never used foul language, and commanded his ship with experienced authority. If any among the crew violated ship protocol — standing in a doorway, opening a tin upside-down, sitting in the skipper’s spot at the galley table — the teaching often came not with words, but with a sharp elbow. Here, Hunter playfully fights back.

Cormack and his wife Phyllis never had children. Bob lost his own father at age six. The two men bonded during the Greenpeace campaigns, with Cormack becoming a sort of surrogate father to Hunter, who always treated the Captain with utmost respect. Cormack was a master of tough love, holding the crew to high standards of work and behaviour. We all learned from him and grew to love him dearly.

My grandmother meets the ship in San Francisco, 1975

This photo was taken with my camera, by a local friend. Three years earlier, I had left the United States as a military draft resister, so when we entered San Francisco after confronting the whaling fleet, I was concerned that I might be arrested. Much to my surprise, rather than being met by federal agents, I was met by my maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Goodwin, who had been a great inspiration in my life, always encouraging me to follow my own heart and my values.

The Vietnam War had ended that spring, and since we had just confronted and embarrassed the Russians, who were illegally killing undersized whales in US territorial waters, the immigration authorities ignored my legal status as a draft resister and treated us like heroes. Behind me on the ship is film cameraman Fred Easton.

The first meeting of Greenpeace International, Amsterdam, November, 1979

The participants in this picture, from the left: Susi Newborn, Art Van Remundt, Hans Guyt, Jon Castle, Tim Mark, Martini Gotje, John Frizell, David McTaggart, Rémi Parmentier, David Moodie of the Fri leaning on pole in the back, Nancy Foote, Peter Balvers, Peter Woof, Louise Trussel, Bill Gannon, Alan Thornton, Glen Jonathans, and Naomi Petersen.

At this meeting, but absent from this image: Bob Hunter, Geert Drieman, Kay Treakle, Pete Wilkinson, and Campbell Plowden.

The building is 98 Damrak, the first Netherlands Greenpeace office, in the centre of Amsterdam. On this day, the original Greenpeace Foundation entrusted all rights to the name and organization to an international council that included representatives from Canada, US, France, UK, Netherlands, Denmark, and New Zealand. Australia and Germany joined soon thereafter. Today: 26 national/regional organisations in over 55 countries around the world.