Every year, on the 23rd of August, the world remembers the slave trade and its abolition. It is a haunting reminder of humanity’s ugly past- of how millions of people (generations upon generations) in Africa were enslaved and tortured, their human rights basically non-existent.

Yet more than 200 years after slavery ended, there are still many living in shackles, grossly abused and treated inhumanely. Modern-day slavery is somehow alive and well, especially here in Southeast Asia.

A Thai purse seiner docked at the maintenance area bound to go under repair in Ranong, southern Thailand.

The deplorable treatment of migrant fishermen working onboard distant water fishing vessels from China, Taiwan, Thailand, the US and the UK have been well documented by international media. These vessels travel the high seas for many months in order to catch tuna and other high value fish that big international companies purchase to process and turn into consumer products.

With the ever growing demand for seafood, commercial fishing vessels need to work overtime and catch as much as they can, whenever they can. For such a labor-intensive business, you would need a lot of man-power. Men from Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines end up working on these ships. Wanting to live a better life, they seek employment abroad. For most, their freedom ends once they step onboard.

With not enough fish left to catch near the shore, fishing vessels would have to go further away (even continents away) just to catch their bounty. A longer travel time would mean higher costs for fuel and supplies. In fishing for profit, the consequences of diminishing returns result to serious labor abuses, including modern-day slavery which exploit vulnerable workers to reduce costs.

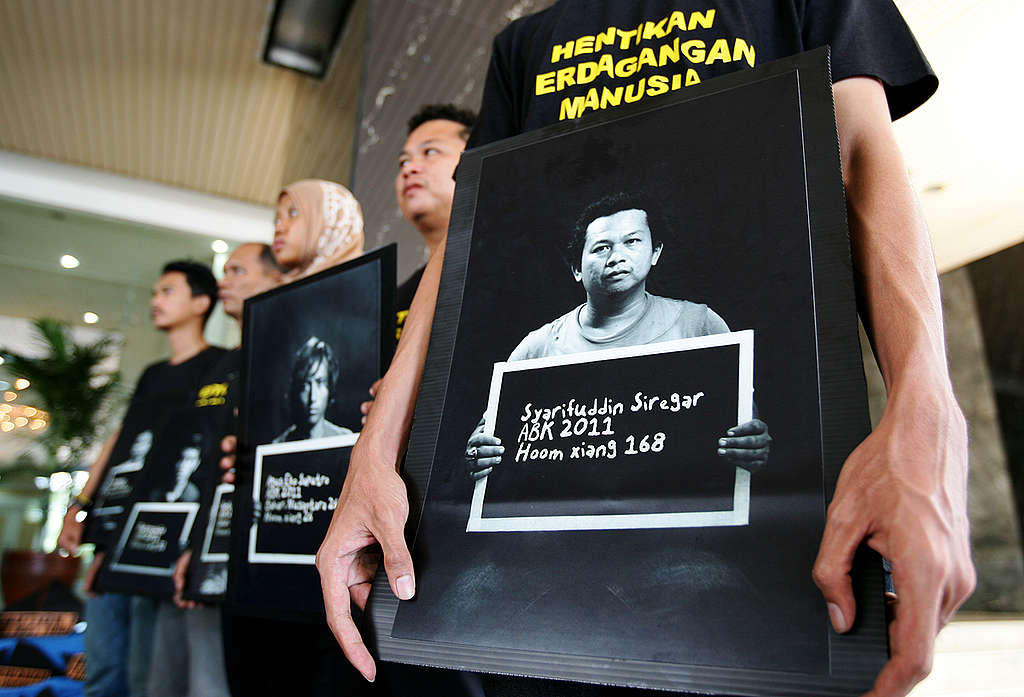

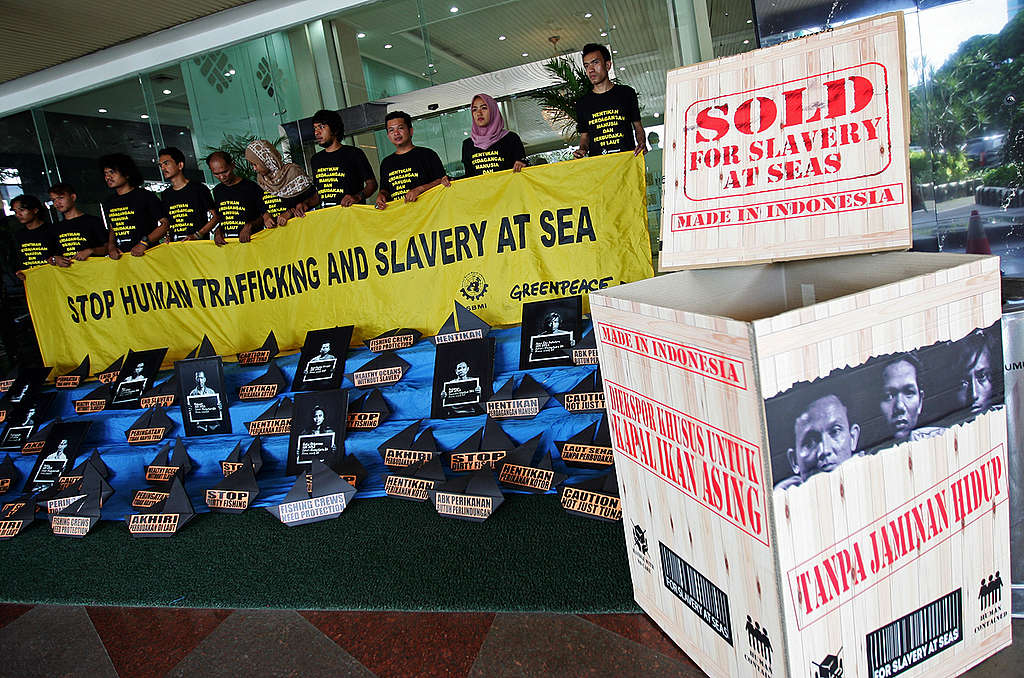

Indonesian activists demand that the Ministry of Manpower carry out its obligations to protect Indonesian fishing crews from human trafficking. The safety and rights of Indonesian fishing crews working on foreign fishing vessels are often neglected by government officials despite news of fishermen being trapped in illegal fishing activities.

The stories are heartbreaking and have become all too familiar: fishermen working 24-hour shifts; men sleeping in cramped spaces; not being adequately fed; not being given medicine when they feel sick; not being given their promised wages; being beaten or maimed when they complain; being kept at will or sold to other vessels as crew; or worse of all, killed and thrown overboard. It seems like a tragic plot out of a Hollywood movie, but these are the current realities for migrant fishermen today.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the Walk Free Foundation, modern-day slavery is described as “any situation of exploitation that a person cannot refuse or leave because of threats, violence, coercion, deception, and/or abuse of power”. This includes “forced labour, debt bondage, forced marriage, slavery and slavery-like practices and human trafficking”.

In 2016, the Indonesian Migrant Workers Union (SBMI) and Greenpeace Indonesia held a peaceful protest in front of the Ministry of Manpower office to call for improvements in placement policies and the protection of migrant crews from Indonesia working on foreign fishing vessels.

A study by the Issara Institute and the International Justice Mission detailed the experiences of Cambodian and Burmese fishers working in Thailand from 2011 to 2016. It found that “fishers can be lured into situations of modern slavery by seemingly legitimate employment opportunities, but once recruited find themselves unable to leave because of the threat of violence towards themselves or family members, physical confinement on- and off-shore, the withholding of wages, and the debts they incur through the recruitment process.”

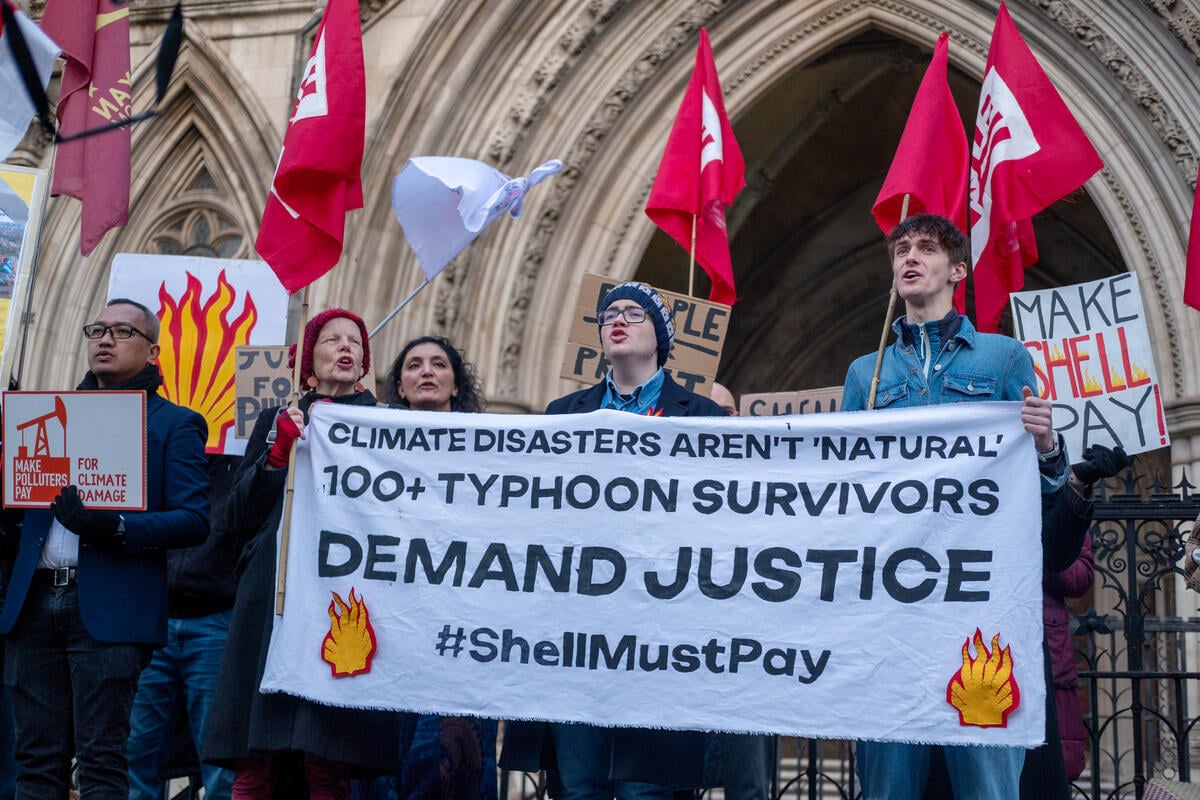

But there is hope even in rough seas. Thanks to international media and human rights groups that have raised the alarm on modern-day slavery at sea, fishermen now have the courage to tell their stories and cry for justice.

In November 2017, the ILO Work in Fishing Convention C-188 (2007), which calls for acceptable living and working conditions for fishers on board ships, came into force. The C-188 has now been adopted by 13 states but the slow ratification and enforcement of labour conventions seem to inhibit effective flag and port-state controls, allowing illegal operators to continue, including illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, as well as the trafficking and exploitation of their workers.

In Southeast Asia, only Thailand has agreed to implement C-188, and so it is imperative that ASEAN governments to adopt it to protect migrant fishermen from further abuse. With regional political undertaking, coupled with meaningful dialogue among key stakeholders (e.g. labor, fisheries, seafarers), we can hopefully eradicate slavery at sea and other illegal activities happening at sea.

Until such time, consumers and seafood lovers, must be vigilant and demand full transparency, responsibility, and accountability from seafood producers to make sure that the fish they sell and profit from is not associated with environmental destruction, nor tainted with any human rights or labour abuse.

We put an end to slavery and colonialism more than 200 years ago. Now, we must break the chains anew to protect our fishermen and uphold their basic human rights. We must put a stop to modern-slavery at sea.

Therese Salvador is a Media Campaigner and an Ocean Defender, based in Manila, Philippines.

The ocean is under attack from all sides and it needs our help to protect it!

TAKE ACTION

Discussion

Quote: “Due to the fact that there is not enough fish left on the coast to fish, fishing vessels would have to go even further (even from the continents) in order to catch their reward.” The fish die, or leave the coast of the Philippines for two reasons: The first one. Coastal water pollution by sewage, fertilizer residues, and other pollutants. Propagation and flowering of poisonous algae, which actively destroy oxygen - the fish either dies or goes into clean waters. Both of these factors are eliminated by producing chilled and oxygen-enriched fresh water, and supplying it to rivers. In the water system of the Philippines, nothing changes. This cannot be done because man will never do better than nature did. It’s just that we cool, purify and enrich the waters of the rivers to their indicators of the middle of the last century. The production of clean fresh water will allow us to grow productive land and pastures, and produce agricultural products and meat of higher environmental quality. Bringing to the norms of water of rivers, surface water bodies and subsoil waters, we will gradually clean and improve the coastal waters of the Philippines. This will allow to revive and double the number of all types of Filipino fish, plus, "alien" ocean fish will come into clean water. Sincerely, Environmental Program Developer, Victor Rodin. Ukraine. Khmelnitsky NPP. Tel Kiev Star: 961336344. Mail: [email protected], [email protected] --- --- --- Цитата: «Из-за того, что у берега осталось недостаточно рыбы, чтобы ловить рыбу, рыболовные суда должны были бы уходить еще дальше (даже от континентов), чтобы поймать свою награду». Рыба гибнет, или уходит от берегов Филиппин по двум причинам: Первое. Загрязнению прибрежных вод сточными водами, остатками удобрений, и другими загрязнителями. Размножение и цветение ядовитых водорослей, которые активно уничтожают кислород – рыба либо гибнет, либо уходит в чистые воды. Оба этих фактора устраняются за счёт производства охлаждённой и обогащённой кислородом пресной воды, и подачи её в реки. В водной системе Филиппин ничего не меняется. Этого нельзя делать потому, что человек никогда не сделает лучше, чем сделала природа. Просто мы охлаждаем, очищаем и обогащаем воды рек к их показателям середины прошлого столетия. Производство чистой пресной воды позволит прирастить продуктивные земли и пастбища, и производить сельхозпродукции и мяса более высокого экологического качества. Приведя к нормам воды рек, наземных водоёмов и подпочвенных вод, мы постепенно очистим и оздоровим прибрежные воды Филиппин. Это позволит возродить и удвоить количество всех видов филиппинских рыб, плюс, в чистую воду придёт «чужая» океанская рыба.