Pacific Nuclear Testing

A history of nuclear testing in the Pacific and the successful campaign to stop it

Michael Szabo – 7 July 2025

Despite a name suggesting peace and tranquillity, about 325 nuclear weapons were detonated in the Pacific region by the governments of the USA, Britain and France between 1946 and 1996. The total cumulative explosive yield was about 173.8 megatons (MT), which is the equivalent to about 11,600 Hiroshima bombs.

As a result of the massive amount of radioactivity released by the atmospheric tests spreading across the globe, it has been estimated that there were about 430,000 additional cancer deaths globally due to cumulative radiation doses by the year 2000.

In the long term, it has been estimated that at least 2 million additional cancer deaths are expected globally due to the longevity of many radioactive isotopes (See: “The Devastating Consequences of Nuclear Testing – Effects of Nuclear Weapons Testing on Health and the Environment”, 2023, Dr Arjun Makhijani & Dr Tilman Ruff, International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons and International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War Germany).

The US Atomic Energy Commission described Rongelap Atoll in the Marshall Islands as, “by far the most radioactively contaminated place on earth.”

Radioactive fallout occurred all over the Marshall Islands as a result of the 67 US nuclear weapon tests carried out there, as shown in the fallout map from the 1954 Castle test series and measurements taken at the time by the US authorities.

Radioactive fallout from the tests contaminated drinking water, land, locally grown foods such as coconuts and other crops, and marine fish. This meant that many local people became sick and died from cancer and other radiation-related illnesses, including some from acute radiation sickness.

Other sources describe infertility, miscarriages, the births of babies with often severe congenital physical malformations, and mental retardation. The tests also resulted in psychological traumatisation and physical displacement of local Indigenous communities.

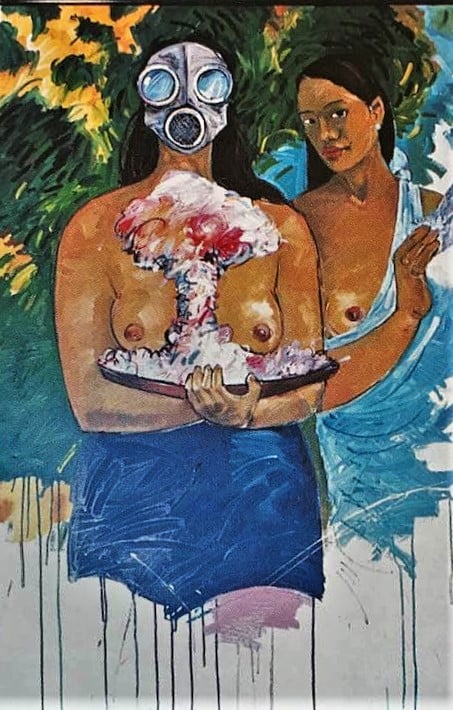

The Makhijani and Ruff report also points out that women and girls have been most affected by radioactivity released by the tests due to the female body having a higher sensitivity to radiation.

There is also a history of elevated levels of radioactivity from nuclear fallout and radioactive contamination at the other test sites in Australia and Kiribati, and of ‘clean up’ operations and the dumping of irradiated equipment on land, in lagoons and at sea.

France ceased publishing public health statistics for French Polynesia in 1963 shortly before it started to test nuclear weapons there in 1966. However, data from the UN International Agency for Research on Cancer for 1998–2002 revealed that women in French Polynesia suffered the highest rates of thyroid cancer and myeloid leukaemia in the world, both types of cancer strongly associated with radiation exposure.

According to a June 2025 report by a cross-party committee of the French National Assembly, tens of thousands of people in French Polynesia are estimated to have been exposed to harmful levels of radiation from the tests, which led to a significant public health crisis which has been largely ignored by French authorities (See: French parliament: Government should apologize for nuclear tests in Polynesia, NHK World, 19 June 2025).

As a result of nuclear fallout and radioactive contamination, the health of people living and working in Australia and Kiribati at or near the British and US test sites there in the 1950s was also impacted, including deaths, cancers, miscarriages, birth defects and genetic mutations.

Fallout and contamination also impacted people in countries beyond the test sites, and people working on fishing vessels at sea.

The failure to collect, store and publish full public health statistics throughout the period of the Pacific tests for all locations means the full impacts such as deaths and ongoing health problems were not fully documented by the testing nations.

Overview of nuclear testing in the Pacific 1946-1996

Of the 325 nuclear tests carried out in the Pacific, about 175 were detonated above ground in the atmosphere and about 150 in “underground” shafts drilled down into coral atolls, including directly beneath lagoons. The test sites were in the Marshall Islands (US), Australia (UK), Johnston (Kalama) Atoll (US), Kiribati (US & UK), Amchitka (US), and French Polynesia Tahiti Nui (France). The precise number of tests is unclear because a small number of the tests listed as ‘failed to detonate’ may have resulted in partial detonations of unknown but significant explosive yields.

The Makhijani and Ruff report (2023) includes many of the main statistical metrics of nuclear testing in the Pacific. Co-author Arjun Makhijani is president of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research (IEER) in Maryland. He received his PhD in 1972 from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, specializing in nuclear fusion.

He has published numerous studies and articles on nuclear fuel cycle issues, including nuclear weapons production and testing, and nuclear waste. His focus has mostly been on nuclear and renewable energy, and on the health and environmental impacts of nuclear weapons production and testing.

Co-author Tilman Ruff is a physician, immediate past co-president and board member of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (Nobel Peace Prize 1985), and an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO). He is also a co-founder, founding chair and Australian board member of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (Nobel Peace Prize 2017) and Honorary Principal Fellow in the School of Population and Global Health at the University of Melbourne.

According to sources cited in the Makhijani & Ruff report, radioactive fallout from the tests carried in dust and rain contaminated drinking water, land, locally grown foods such as coconuts and other crops, and marine fish.

Their report also describes how the radioactive fallout from the atmospheric tests and the subsequent ingestion of contaminated water and foods meant that many local people became sick and died from cancer and other radiation-related illnesses, including some from acute radiation sickness.

Other sources describe infertility, miscarriages, the births of babies with often severe congenital physical malformations, and mental retardation. The tests also resulted in psychological traumatisation and physical displacement of local Indigenous communities.

The French government’s underground nuclear tests carried out at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls also deposited very large amounts of radioactivity underground, including some radioactive isotopes which take thousands or millions of years to decay.

They also damaged the stability of the surrounding rock and nearby corals, including fracturing and fissures, allowing radioactivity to escape, and increasing the likelihood of its release into local groundwater, lagoons, the surrounding sea, and the atmosphere (via venting).

The indigenous Mā’ohi spelling is Moruroa rather than the misspelling Mururoa used by French cartographers in the 1960s. The original Mangarevan meaning of Moruroa is “place of the great secret”.

Nuclear warheads detonated at coral atolls in the Marshall Islands, Kiribati and Tahiti Nui (French Polynesia) also killed marine life in them, including dolphins, dugongs, turtles, seabirds, land birds, fishes, shellfish and corals, and contaminated the land and local food crops, including coconuts, and marine food chains. We know this from descriptions of dead marine life in and around lagoons after the tests and the existence and persistence of radioactive contamination in the soil, crops such as coconuts, and in marine food chains measured decades later.

The Makhijani and Ruff report also warns that rising sea levels resulting from climate change and an increase in the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events such as tropical cyclones will only add to the problem.

It cites the example of the huge concrete Runit Dome in the Marshall Islands, where tens of thousands of cubic metres of radioactive waste was dumped into a crater gouged out by a US nuclear weapons test and then covered with a concrete dome. That concrete structure is not sealed off from the ground underneath it, so it is in direct contact with the rising ocean and erosion.

2 million additional cancer deaths worldwide

According to the introduction to Makhijani and Ruff’s report, written by Angelika Claußen, Inga Blum and Juliane Hauschulz: “The radioactivity released by above-ground nuclear tests has spread through the atmosphere across the globe, resulting in about 430,000 additional cancer deaths due to cumulative radiation doses by the year 2000 alone. In the long term, at least 2 million additional cancer deaths can be expected due to the longevity of many radioactive isotopes.”

Their introduction also identifies another important aspect of the history of nuclear weapons testing as the associated racism evident in the selection of the test sites far from the metropolitan capitals of the nuclear testing states and in many cases, the different radiation protection standards applied to residents of the affected areas and others, such as members of the military, technicians and scientists involved in carrying out the tests.

The report quotes from a 1957 British report on a nuclear weapons test at the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony (now the Republic of Kiribati) which stated: “The radiation dosage … is about 15 times higher than that which would be permitted by the International Commission on Radiological Protection … but only a very slight health hazard would arise, and that only to primitive people.”

Residents of the US nuclear weapons test sites in the Marshall Islands were also included in unethical medical studies without their consent in order to study the effects of radioactive contamination on the human body. When the residents of Rongelap Atoll were taken back to their island, a representative of the US Atomic Energy Commission said: “This island is by far the most radioactively contaminated place on earth, and it will be very interesting to see what the uptake of radioactivity is when people live in this environment.”

The report also notes that samples were taken from the blood, bone marrow and internal organs of the people of Rongelap, and some were compelled to undergo experimental surgery or received injections with radioactive substances. In Australia, the bones of deceased people – especially children – were taken from hospitals for years to be examined in the US without the knowledge and consent of affected families. There were also harrowing reports of families denied access to their dead children.

A summary with photos and film footage about US nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands can be viewed online.

In these and other ways, the Pacific was at the centre of the superpower confrontation of the Cold War period. For example, the US bombers that dropped the first nuclear weapons on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan in August 1945 departed from Tinian in the Northern Mariana Islands.

These horrific weapons of mass destruction were developed and refined by the five declared nuclear weapons states (USA, USSR, Britain, France, China) in the full knowledge that they had the power to destroy entire cities and indiscriminately kill civilians living in and around them.

Although the Cold War supposedly ended in 1990, its radioactive legacy remains and is a constant threat to human health, the environment, and future generations.

During the Cold War, the US government carried out more nuclear weapons tests than any other country (1,054). It detonated a total of 67 nuclear warheads in the atmosphere at the Marshall Islands in Micronesia between 1946 and 1958, mainly at Bikini and Enewetak atolls.

The US nuclear weapon used to bomb the city of Hiroshima in Japan on 6th August 1945 had an explosive yield of about 15 kilotons (KT). It killed between 90,000 and 166,000 people out of a population at the time of 350,000, 90% of which were civilians. About half of the people killed died in the first hour. The rest died from the effects of radiation burns, radiation sickness, and other injuries caused by the bombing over the next four months (See: Hiroshima, John Hersey, Knopf, 1946; Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Wikipedia, 1 July 2025).

The bomb detonated about 600m above the ground at 8:15am and the resulting fireball had a core temperature of several millions degrees. In the area directly below the blast people were vaporised. Further out, people’s bodies including their bones were turned to ash. The blast was followed by a ‘black rain’ of radioactive ash or ‘fallout’ and the city continued to burn through the following night.

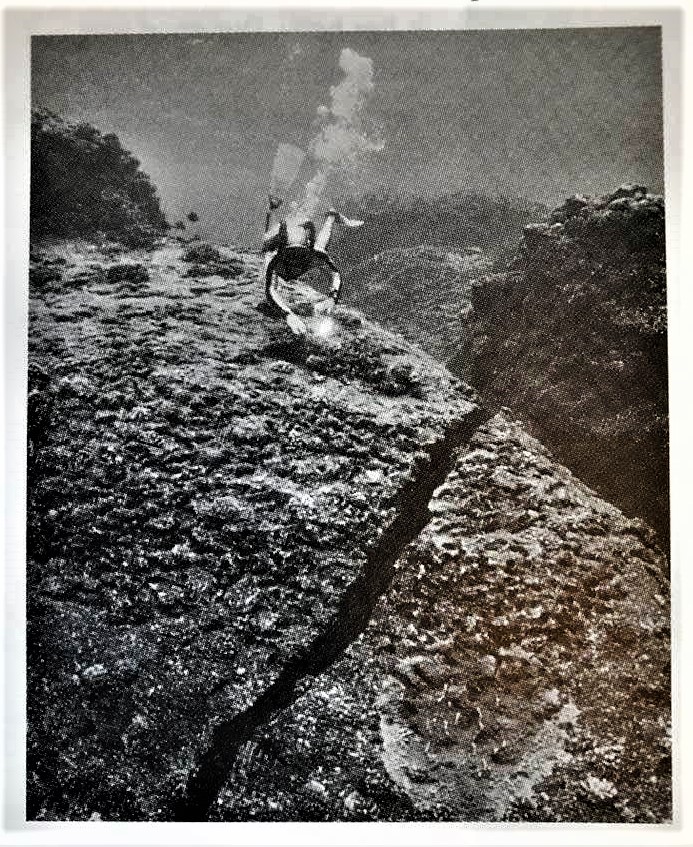

For comparison, the second ‘Operation Crossroads’ Baker nuclear test explosion detonated by the US military in the lagoon at Bikini Atoll on 24 July 1946 was 23 KT. Footage of that explosion can be viewed online.

11,600 Hiroshima bombs detonated in the Pacific

The 67 US nuclear warhead tests in the Marshall Islands had a total combined explosive yield of about 108.5 megatons (MT), one megaton being about one thousand times more powerful than one kiloton. So, 108.5 MT is the equivalent of about 7,250 Hiroshima bombs.

The US also detonated 15 nuclear warheads at high altitude above Johnston (Kalama) Atoll, about 700 nautical miles south-west of Honolulu in Hawai’i, between 1958 and 1962, an atoll under the jurisdiction of the US Air Force. The 15 tests carried out there had a total combined yield of about 14.2 MT, which is the equivalent of about 950 Hiroshima bombs. Five of those tests were listed as “unknown yield”.

The US detonated a further 24 nuclear warheads in the atmosphere in the Christmas Islands (Kiritimati and Malden) area in 1958 (now part of the Republic of Kiribati) with a total combined yield of about 24 MT, which is the equivalent of about 1,600 Hiroshima bombs.

There were also 3 underground US nuclear warhead test detonations at Amchitka Island in the Aleutian Islands of Alaska in the north-west Pacific between 1965 and 1971 with a total combined yield of about 6 MT, which is the equivalent of about 400 Hiroshima bombs.

The British government detonated 12 nuclear weapons in the atmosphere in Australia between 1952 and 1957 at the Monte Bello Islands in Western Australia, Emu Field in South Australia, and Maralinga in South Australia. The total combined yield was about 180 KT, which is the equivalent of about 12 Hiroshima bombs.

After Australia refused to allow Britain to test its first hydrogen bomb there, Britain carried out another 9 atmospheric nuclear warhead tests at Kiritimati Island in 1958 (known as Christmas Island at that time, now part of the Republic of Kiribati). They had a total combined yield of about 7.8 MT, which is the equivalent of about 520 Hiroshima bombs.

Britain had requested permission to move its atmospheric nuclear testing to the Rangitāhua Kermadec Islands in Aotearoa in 1955 but the New Zealand government of the day refused permission, fearing doing so would trigger strong public opposition.

On 3 July 1970, France carried out its largest nuclear test up to that time on Fangataufa Atoll with an explosive yield of 914 KT, equivalent to about 60 Hiroshima bombs.

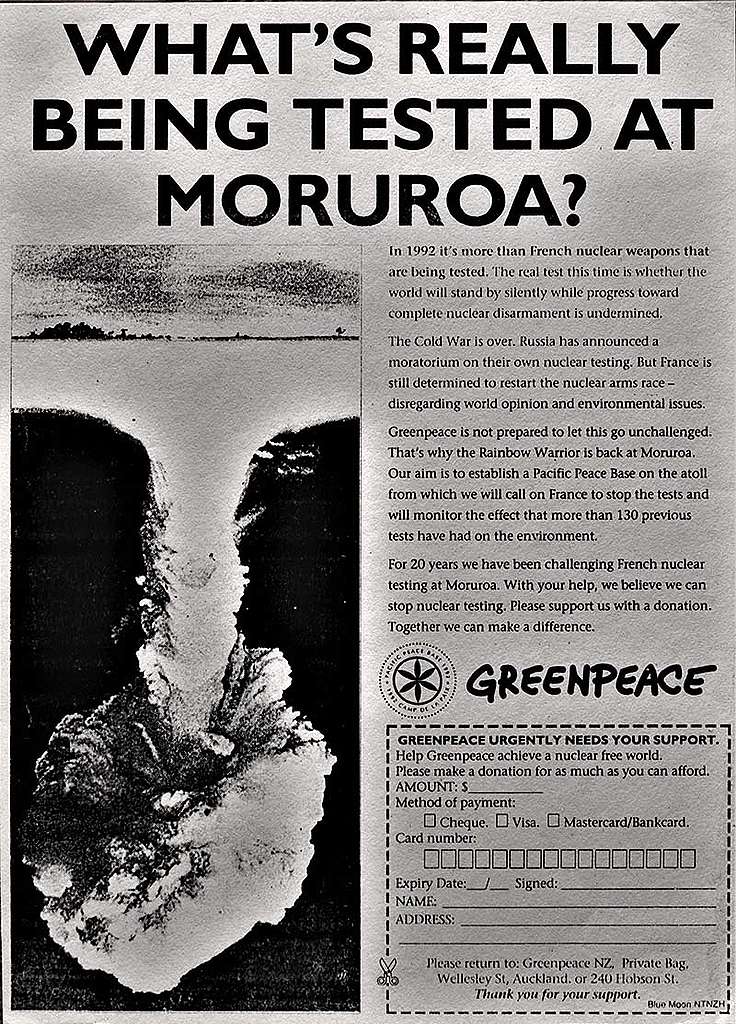

The French government detonated 193 nuclear weapons (46 in the atmosphere, 147 in shafts drilled into coral atolls) in Tahiti Nui (French Polynesia) at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls between 1966 and 1996.

The total combined yield of all the atmospheric French nuclear tests there between 1966 and 1974 was about 10.1 megatons, which is the equivalent of about 800 Hiroshima bombs. The total combined yield of the ‘underground’ tests there from 1975 to 1996 was about 2.8 MT, which is the equivalent of about 200 Hiroshima bombs. In total, that is the equivalent of about 1000 Hiroshima bombs.

The combined total yield for all atmospheric nuclear tests in the Pacific was about 165 MT, which is the equivalent of about 11,000 Hiroshima bombs. The combined total yield for all the underground nuclear tests in the Pacific was about 8.8 MT, which is the equivalent of about 600 Hiroshima bombs.

So, the total cumulative yield for all atmospheric and underground nuclear tests in the Pacific was about 173.8 MT, which is the equivalent to about 11,600 Hiroshima bombs.

These so-called ‘tests’ had devastating impacts on Indigenous Marshallese, Australian Aboriginal, Ni-Kiribati, Mā’ohi and Unangax̂ Aleut communities. They also wrecked local ecosystems and left a deadly legacy of radioactive contamination and health problems that persist today.

For example, radioactive plutonium-239 is released into the environment during nuclear weapons tests. It is highly radioactive and toxic, and has a half-life of 24,100 years, which means it takes that long for half of a sample amount to decay.

The two main superpowers of that period were the USA and the Soviet Union (successor state, Russia). Along with their respective allies, Britain and France, and China, they vied for nuclear superiority. They also sought to develop bigger and deadlier nuclear weapons systems, refining and modernising them until there were about 50,000 nuclear weapons by 1990. Most of those nuclear weapons were in the US and Soviet nuclear arsenals as Britain, France and China each had smaller nuclear arsenals. Between them, they had enough to destroy life on Earth many times over.

The military on each opposing side also had access to massive budgets and had very large numbers of scientists and engineers on their payrolls. For example, about 600,000 people worked on the Manhattan Project at various points during its operation including scientists, engineers, construction workers, and support staff, and it cost the equivalent of about US$30 billion in 2023 dollar value.

They built and operated nuclear reactors, nuclear laboratories and various other sites associated with mining and refining uranium and the nuclear fuel cycle, plus the main location at Los Alamos. Shortly after World War Two, the Soviet Union copied the Manhattan Project.

The focus was on improving their nuclear weapons and pre-empting or countering the other side’s innovations. Imagine for a moment if instead all that money and expertise had been invested over those five decades in improving public health and education, alleviating poverty, hunger and inequality, and developing sustainable solutions to humanity’s energy needs and environmental problems.

Although there was a powerful ideological dimension to the Cold War, the great extent of power and financial resources which those who controlled the military-nuclear complexes of the nuclear testing nations wielded made it extremely difficult for citizens in civil society to stop nuclear testing. The following section describes how it was stopped.

The successful campaign to stop nuclear testing in the Pacific

Nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific did not go unchallenged at the time it was happening. The campaign to stop the tests quickly spread to become a global movement, bringing together Pacific peoples, peace activists, ecologists, church groups, women’s groups, scientists and political leaders around the world in a struggle against nuclear colonialism and environmental destruction.

Scientists warn about the dangers of nuclear war and testing

As the US government prepared to conduct its first nuclear weapons tests in the Marshall Islands in 1946, there was reportedly diplomatic pressure to cancel the tests and some Manhattan Project scientists argued that further testing was unnecessary and environmentally dangerous.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, the US physicist who oversaw the development of the first nuclear weapons, rejected an invitation from US President Truman to witness the 1946 tests. In his reply he set out his objections and said that any data from the tests could have been obtained more accurately and cheaply in a laboratory.

At a 22 March 1946 cabinet meeting, US Secretary of State James F. Byrnes reportedly said, “from the standpoint of international relations it would be very helpful if the test could be postponed or never held at all.” President Truman delayed the 1946 test series but eventually it went ahead on 30 June followed by another test on 21 July. A planned third test on 1 March 1947 was cancelled due to the devastating impacts of the first two.

Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Joseph Rotblat was the only nuclear scientist to actually withdraw from working on the Manhattan Project in the US during World War Two due to his conscientious objections to nuclear weapons. He left the project after it became clear in 1944 that Nazi Germany had ceased its development of a nuclear weapon. The Manhattan Project had been established in 1942 to beat Nazi Germany to building the first nuclear weapon.

After he heard news of the US nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, fearing an impending nuclear arms race between the USA and the Soviet Union, he said that he “became worried about the whole future of mankind”.

During the 1940s and 1950s, Nobel Prize Laureate Bertrand Russell joined Joseph Rotblat in advocating for nuclear disarmament. Another Nobel Prize Laureate, Albert Einstein, dedicated the last decade of his life (1945-55) to the cause of nuclear disarmament, also highlighting the dangers of nuclear weapons. During the 1950s the three of them began a collaboration with other physicists to draft what became known as the Russell–Einstein Manifesto.

Albert Einstein signed it shortly before he died in April 1955 and it was launched publicly in July 1955 in London. The manifesto highlighted the dangers posed by nuclear weapons and their testing, and called for a conference of scientists to assess the dangers of nuclear weapons.

One of the 11 signatories was Herman Muller, an American scientist who was awarded the 1946 Nobel Prize for Medicine for the discovery that X-rays can cause mutations, and who warned of the long-term dangers of radioactive fallout from nuclear testing.

Shortly after the launch of the manifesto, the first conference was organised by Joseph Rotblat and Bertrand Russell in July 1957 in Pugwash, Canada, which became known as the Pugwash Conference. Joseph Rotblat served as secretary-general of the annual Pugwash Conference, which brought together nuclear physicists from around the world and across the East-West divide, and went on to play an essential part in the successful negotiations on the Partial Test Ban Treaty and other arms control agreements. Joseph Rotblat and the Pugwash organisation were later jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1995.

Early opposition and protests against US testing in the Pacific

The people of the Marshall Islands actively opposed US nuclear testing during the 1940s and 50s. Marshallese leaders repeatedly petitioned the UN and the US to end the nuclear tests and to relocate communities. The government of the Marshall Islands strongly opposed US nuclear testing, and continues to seek justice and reparations for the long-term health and environmental impacts of the tests since they ended there in 1958.

The Nitijela, the parliament of the Marshall Islands, repeatedly condemned US nuclear testing, and advocated for nuclear disarmament and justice for the lasting harms caused by the tests there. The statements made by the Nitijela repeatedly highlighted the health impacts, environmental contamination, and cultural disruption caused by the tests, and urged the US government to acknowledge the impacts and compensate for them.

According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, former Marshall Islands Foreign Minister Tony deBrum, who witnessed the Castle Bravo test as a 9-year-old child, argued that the tests caused health and infrastructure problems and that the lives of the Marshallese victims were sacrificed in the pursuit of developing US nuclear weapons.

The people of the Marshall Islands were never consulted or informed about the US tests and they never gave their permission for the tests to be conducted there.

Jeton Anjain (1933-1993), a senator in the Nitijela representing Rongelap who was also a Minister of Health, described the effects of the huge Castle Bravo test as follows: “Five hours after detonation, it began to rain radioactive fallout at Rongelap. The atoll was covered with a fine, white, powder-like substance. No one knew it was radioactive fallout. The children played in the ‘snow.’ They ate it.”

Later, in 1985, it was Jeton Anjain who asked Greenpeace to help organise Operation Exodus in which the Rainbow Warrior evacuated the people of Rongelap and their possessions to Mejatto.

Then in 1991, he and the people of Rongelap were awarded the Right Livelihood Award for, “their steadfast struggle against United States nuclear policy in support of their right to live on an unpolluted Rongelap island.” Jeton Anjain died of cancer in 1993.

Darlene Keju (1951-1996) was from a younger generation of Marshallese activists. She grew up at Wotje Atoll. Later, she lived in Ebeye and then Honolulu in Hawai’i. During her life she travelled around the Marshall Islands, Hawai’i and North America speaking out about the nuclear tests, and using music, dance and song to express outrage about her people’s forced evacuations and resettlements, the false promises made to them by the US authorities, and the ongoing health problems they suffered from caused by radiation exposure.

When she visited some of the more remote Marshall Islands atolls, she met women who had suffered miscarriages and had babies with birth defects, so-called “jellyfish babies” – babies born without bones due to radiation exposure.

As one of the first prominent anti-nuclear activists in the Marshall Islands, her work gained international attention, and she supported other nuclear survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. She also delivered powerful speeches, including at the 1983 World Council of Churches gathering in Vancouver, Canada.

Darlene Keju died in 1996 from breast cancer, but her legacy lives on. Her husband, Giff Johnson (son of US anti-nuclear activist and Greenpeace Aotearoa co-founder Bette Johnson), wrote a 2014 book about Darlene entitled “Don’t Ever Whisper: Darlene Keju, Pacific Health Pioneer, Champion for Nuclear Survivors” to ensure the tragic injustice suffered by the people of the Marshall Islands will never be forgotten. More information is available online about the inspiring, world-changing work of Marshallese women activists.

Anti-nuclear movements in Japan, Britain, USA, New Zealand, Australia and Canada

On 1 March 1954, a Japanese tuna fishing boat, Daigo Fukuryū Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5), was operating 180km east of Bikini Atoll, about 30km outside the US military exclusion zone, at the time of the 15 MT Castle Bravo nuclear test. Several hours after the blast, radioactive fallout ‘dust’ comprising irradiated particles of coral and sand from Bikini fell from above, settling on the boat. After retrieving their fishing gear the boat headed away and some of the crew collected up the ‘dust’ with their hands and filled bags with it to clean the deck. They suffered high radiation exposures and acute radiation illnesses after they breathed in particles of the fallout or came into contact with it through touching it.

After arriving back in Japan, eight of the 22 crew members were hospitalised with radiation sickness. On 23 September 1954, Kuboyama Aikichi, the chief radio operator, died. Other crew members were eventually discharged from hospital but subsequently had a history of cancer or other serious diseases.

It was estimated that about one hundred fishing boats were contaminated to some degree by fallout from the Castle Bravo test. Despite denials by Lewis Strauss, head of the US Atomic Energy Commission, about the extent of the claimed contamination of the tuna caught by Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5) and the other fishing boats, US authorities subsequently imposed rigid restrictions on tuna imports.

After the Daigo Fukuryū Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5) tragedy and fears of radioactive contaminated fish, the Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun published reports about the damage that radiation can cause, which helped instill a fear of radiation among the Japanese public. The fishermen involved and a group of housewives started a petition against the hydrogen bomb tests. They first gathered together through a reading circle in the Suginami district of Tokyo, mainly concerned about being exposed to irradiated fish.

The ‘Suginami Appeal’ galvanised people in other cities and led to the organisation of a new anti-nuclear movement in Japan. In 1955 a ‘World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs’ was held in Hiroshima followed by the establishment of a committee to organise nationwide cooperation against nuclear weapons called Gensuibaku Kinshi Nihon Kyōgikai (Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs), or Gensuikyō.

(See: Japanese Anti-nuclear Movements – Local and Transnational Characteristics of Peace Protest in Hiroshima, Makiko Takemoto).

Also after the Castle Bravo test, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru called for a moratorium on nuclear testing and British Labour Party leader Clement Atlee called for a ban on hydrogen bomb tests. A Soviet proposal which closely resembled an Anglo-French proposal for a test ban was rejected by the US in 1955 during the presidency of Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower. By 1957, polls showed 63% of Americans supported a test ban and a petition supporting a test ban launched by Nobel Prize Laureate Albert Schweizer was signed by more than 9,000 scientists from 43 countries, including Albert Einstein.

Following the publication of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto in 1955, Bertrand Russell, Joseph Rotblat, Peggy Duff and others founded the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) in London in November 1957.

The CND was publicly supported by a ‘Who’s Who’ list of leading British writers, artists, scientists, peace activists and church leaders of the period, including E.M Forster, Benjamin Britten, A. J. P. Taylor, J.B. Priestley, Jacquetta Hawkes, Doris Lessing, Kingsley Martin, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Herbert Read, Flora Robson, Peggy Ashcroft, Michael Tippett, E.P. Thompson, Fenner Brockway, Eric Baker, Compton Mackenzie, Canon John Collins, Rev. Trevor Huddleston, the Bishop of Llandaff Dr Glyn Simon, the Bishop of Birmingham Dr J.L. Wilson, Bruce Kent, Julian Huxley and Conrad Waddington. Several British Labour party figures were also early supporters, including Michael Foot, Anthony Greenwood, Gerald Gardiner and Frank Allaun.

According to Nic Maclellan (See: Grappling with the Bomb: Britain’s Pacific H-bomb tests, Nic Maclellan, ANU Press, 2017), Japanese peace activist Takeko Kawai of the ‘Peace Protection Association of Toyohashi Citizens’, who was the wife of the president of Aichi University (Kiyoshi Kawai), organised some protests against US and Soviet atmospheric hydrogen bomb testing.

She also sent a letter to peace activists in the US, France and Britain, in which she asked for international support for direct action opposing the upcoming British hydrogen bomb test series at Christmas Island (now in the Republic of Kiribati).

In March 1957, reportedly inspired by her letter, veteran British peace activist Harold Steele announced that he would travel to Tokyo with the aim of joining a protest fleet to sail to Christmas Island (Republic of Kiribati) in the central Pacific to stop the planned British hydrogen bomb tests there.

In London, the Emergency Committee for Direct Action Against Nuclear War was formed in April 1957 to raise funds to support the planned direct action, with sponsors including Bertrand Russell, playwright Laurence Houseman and Irish writer and actor Spike Milligan.

(See: Putting your life on the line: Harold Steele, A forgotten story of global solidarity, the birth of the Direct Action Committee and the inspiration for the first environmental direct action boat, the Golden Rule, Peace News, 1 August 2023; Archive of the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War, Special Collections, J.B. Priestley Library, University of Bradford, Ref code GB 0532 CWL DAC, 1957-61).

After repeated delays in receiving a visa to travel to Japan, Steele arrived in Tokyo via India on 16 May 1957. En route he stopped in India where he met Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru who he said “wished him well” on his mission.

On 22 May, Harold Steele was present at the Executive Council of a Japan Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs meeting which debated the pros and cons of sending a protest fleet into the Christmas Island test site ‘danger zone’.

A proposed meeting with Japan’s Deputy Prime Minister Mitsujiro Ishii was also repeatedly delayed and so organising a vessel for the proposed protest fleet proved to be much harder than expected (Maclellan, 2017).

Without the capacity to mobilise a protest flotilla, the Council focussed on organising protests against the tests within Japan. Regular reports from the Reuters Tokyo office were published around the world. News media in the Pacific Islands also covered the anti-nuclear protests in Japan, including a front-page report in the Fiji Times of a 15,000-strong rally in Tokyo (Maclellan, 2017).

The British Embassy in Tokyo sent daily reports to London on the unsuccessful efforts by Japanese peace activists to organise protest boats to travel to the test site.

In Kochi, about 100km south of Hiroshima, activists reportedly continued

to mobilise for the protest. The Kochi Prefectural Committee for the Prevention of Nuclear Tests on Christmas Island had planned to send a steamer with 27 crew and eight demonstrators on board to the area near the danger zone for 100 days, as a symbolic protest and to collect samples of radioactive fallout. Soon after the first (300 KT) test in the Grapple series was carried out on Malden Island on 15 May 1957, the British Embassy reported that the Japan Council was supporting the Kochi Prefectural Committee with a ¥3.5 million contribution towards the ¥8.5 million cost of chartering and outfitting fishing boats to travel to the test zone (Maclellan, 2017).

However, on 19 May, four days after the first test, the British Embassy reported that the Kochi committee had ‘announced cancellation of its plan to send vessel to the testing grounds in view of danger of contamination from [the] first test’.

Unable to find a way to reach the testing zone around Christmas Island, Harold Steele travelled back to Britain in August 1957. His supporters formed the DAC and proposed instead the organisation of a march to protest at the British nuclear weapons factory at Aldermaston where the warheads to be detonated in the tests were assembled (See: Emergency Committee for Direct Action Against Nuclear War/Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War, 1956-1961, Reference number CND/2008/2, London School of Economics Archive).

The DAC consisted of Allen Skinner, Hugh Brock, Arlo Tatum, Michael Randle, April Carter, Pat Arrowsmith, Walter Wolfgang, Frank Allaun and Rev. Michael Scott. Sponsors and public supporters of the DAC included Bertrand Russell, Doris Lessing, Linus Pauling, Spike Milligan, George Melly, John Osborne, Bayard Rustin, John Berger and Alex Comfort.

Dr Sheila Jones also played an important role in opposing nuclear testing and the founding of the CND. From 1955 she was secretary of the Joint Local Committee for the Abolition of Nuclear Bomb Tests in Hampstead, London. The Committee distributed leaflets, held public meetings, sponsored film shows and organised a letter-writing campaign. In 1957 she joined Ianthe Carswell in founding the National Council for the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons Tests and then in 1958 they agreed to transfer all of its resources (funds, office, staff) to the newly founded CND.

The CND worked with the DAC to organise the first protest march from London 100km to the British nuclear warhead factory at Aldermaston during Easter 1958. Afterwards, the DAC changed its name to the ‘Committee of 100’ and became the direct action wing of the CND, which subsequently grew into a mass movement. CND affiliated groups were soon established in other countries, including New Zealand (1957-59).

Early Aldermaston marchers included Canadian journalist Bob Hunter and Kiwi photographer Gil Hanly. Bob Hunter went on to be a co-founder of Greenpeace in Canada in 1971 and for decades Gil Hanly has documented anti-nuclear flotillas and peace movement activities in Aotearoa, including photographing the Rainbow Warrior the morning after it was bombed.

In 1959, responding to increasing public concern after the British hydrogen bomb tests in the Pacific, the New Zealand government voted at the UN to condemn nuclear testing while the US, Britain and France voted against, and Australia abstained.

In Canada, two anti-nuclear testing groups also emerged, the Combined Universities Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CUCND) in 1959 and the Voice of Women (VOW) in 1960.

According to Patricia I. McMahon (1999), the CUCND was established in November 1959 by a group of students from the three Montreal area universities and took their inspiration from the British CND and Aldermaston march of Easter 1958. Their first action was to organise an anti-nuclear petition that they delivered to Canada’s prime minister on Christmas Day 1959.

Then in May 1960, Brenda Dempsey announced the creation of a new women’s

organisation focused on disarmament and international peace (McMahon, 1999). She received hundreds of letters of support, as did Josephine Davis, after she appeared on a segment of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s “Frontpage Challenge” programme. The two had met at the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of South Peel. A third woman, Helen Tucker, helped organise a rally sponsored by the Toronto Campaign for Disarmament at Massey Hall, and reportedly persuaded Davis to participate. Dempsey reportedly helped to raise awareness of the threat posed by nuclear weapons and testing through her newspaper column.

(See: The Politics of Canada’s Nuclear Policy, 1957-1963, Patricia 1. McMahon,

PhD Thesis, 1999, University of Toronto).

In 1961, the New Zealand CND urged the NZ government to declare it would not acquire or use nuclear weapons and withdraw from nuclear alliances such as ANZUS. In 1963, the Auckland CND campaign submitted its ‘No Bombs South of the Line’ petition to the NZ parliament with 80,238 signatures calling on the government to sponsor an international conference on establishing a nuclear free zone in the southern hemisphere.

After it emerged that France was looking to move its nuclear testing programme to French Polynesia, New Zealand CND members including Mabel Heatherington, Alison Duff and Pat Denby delivered protests to the French Embassy in Wellington and visiting French warships during 1963-64.

In 1964, small peace marches which featured “Ban the Bomb” placards were organised in several Australian state capital cities.

According to New Zealand CND member Richard Northey (who was later elected as a Labour MP in Mt Eden and became New Zealand’s first Disarmament Minister in the 1980s) there was an attempted protest yacht voyage from Australia to Tahiti in 1965 which he helped to support but due to the crew’s inexperience, they were unable to make it further than Rarotonga.

Later, in 1972, Richard Northey and other New Zealand CND members worked with other groups such as Peace Media (newly founded by Barry and Jacqui Mitcalfe) and many individuals including Maurice Shadbolt and Willem and Ann van Leeuwen to help organise and support the first Greenpeace protest voyage of the Vega (renamed Greenpeace III) from Aotearoa to the French nuclear test site at Moruroa Atoll.

The Golden Rule and the Phoenix of Hiroshima

Despite his failure to get to the Christmas Island test site, Harold Steele’s efforts received international media coverage, helping to inspire others to campaign against the hydrogen bomb and nuclear weapons testing.

According to Non-Violent Action Against Nuclear Weapons (NVAANW) founder Lawrence Scott, protest actions carried out at the US Nevada nuclear weapons test site in 1957 and a subsequent 1958 protest voyage to the Marshall Islands by a yacht named The Golden Rule were inspired by news of Harold Steele’s plan to join the protest flotilla from Japan to Christmas Island in 1957 and the planned Aldermaston Easter march (See: Putting your life on the line: Harold Steele, Peace News,

1 August 2023).

Later in 1957, NVAANW changed its name to the Committee for Non-Violent Action (CNVA). On 6 August 1957, the 12th anniversary of the US bombing of Hiroshima, Albert Bigelow and 12 other members of the CNVA were arrested when they tried to enter the Camp Mercury nuclear test site in Nevada, USA. The following day, they returned and sat with their backs to the site as the nuclear test took place.

After that, they planned a peaceful protest voyage to the Marshall Islands that aimed to disrupt the US tests there, gain international attention and inspire others to protest.

On 31 December 1957, Albert Bigelow tried to present a 17,000 signature petition against nuclear testing to US President Eisenhower, which had been collected by the CNVA and the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker-founded US peace and social justice non-governmental organisation.

Albert Bigelow and the CNVA then sent a letter to President Eisenhower on 8 January 1958, asking him to stop the scheduled tests in the Marshall Islands. The letter said if the president stopped the plans for the nuclear tests, CNVA would not attempt to sail its yacht into the nuclear test zone, but they received no reply.

Harvard educated architect Albert Bigelow was also a World War Two veteran, having commanded a US warship in the Solomon Islands. He became a pacifist after hearing news that the US had attacked Hiroshima with a nuclear bomb. The CNVA chose him to be the skipper and after recruiting crew members George Willoughby, William R. Huntington, Orion Sherwood, and James Peck, bought a small yacht with two masts which they named The Golden Rule.

The five of them planned to sail into the nuclear test site at the Marshall Islands to peacefully protest against the testing. CNVA publicised the protest voyage in advance in order to attract more public support and the yacht set sail in early March 1958 from California to Hawai’i.

On 11 April 1958, in anticipation of the protest, the US Atomic Energy Commission issued a ban against sailing into the test area. The ban was put into effect when The Golden Rule was en route to Honolulu. On 1 May 1958, The Golden Rule set sail from Honolulu towards the Marshall Islands despite the court injunction. The US Coast Guard arrested Bigelow and his crew just five nautical miles from Honolulu and brought them back to port (See: The Golden Rule and Phoenix voyages in protest of U.S. nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands, 1958, Global Nonviolent Database).

The Golden Rule crew attempted to depart a second time on 4 June to the ‘Eniwetok Proving Grounds’ in the Marshall Islands, but they were arrested again and the court sentenced Bigelow and the crew to 60 days in jail.

The interrupted voyages and public statements of the crew inspired Earle and Barbara Reynolds, US citizens in Honolulu at the time of the court proceedings. Earle Reynolds was an anthropologist who studied the effects of the Hiroshima bombing on Japanese society. Speaking with Bigelow inspired him and Barbara to take a second yacht, the Phoenix of Hiroshima, and to continue on The Golden Rule’s route. In early July, the Phoenix of Hiroshima sailed successfully to the testing area at the ‘Proving Grounds’, but the US Coast Guard arrested them there. A court sentenced Earle and Barbara Reynolds to nine weeks in jail.

Although The Golden Rule and the Phoenix of Hiroshima protests did not stop US nuclear testing, the publicity they generated gained their cause international support. In London, Montreal, and various US cities, groups of sympathizers formed picket lines in support of The Golden Rule and Phoenix of Hiroshima protests.

In San Francisco, over 400 people sought arrest by petitioning the District Attorney’s office to arrest them because they supported The Golden Rule’s crew. The Golden Rule protest and the work of the CNVA heavily influenced fellow Quaker Marie Bohlen to suggest the use of a similar tactic to members of the Vancouver-based ‘Don’t Make a Wave Committee’ in 1970, which later evolved into Greenpeace in 1971 and organised the first Greenpeace protest boat to sail to the US nuclear test site at Amchitka in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska.

In 1961, at the height of the Cold War, about 50,000 women brought together by ‘Women Strike for Peace’ marched in 60 US cities in protest at nuclear weapons, including their testing. The new US President, Democrat John F. Kennedy, reportedly watched the Washington DC march from the White House.

These various actions that sought to stop nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific helped to inspire wider public mobilisations that together increased the pressure on the nuclear weapons states to agree to ban nuclear testing.

Spurred by public opposition and the experience of the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, the US, Soviet Union and Britain signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty in August 1963 and agreed to move their tests underground. However, France and China did not. France had tested its first nuclear weapon in Algeria in 1960 and China carried out its first nuclear test in 1964, both in the atmosphere.

Pacific-led opposition to French nuclear testing in Tahiti Nui

As soon as news spread that France was looking for a new nuclear test site in Tahiti Nui (French Polynesia) after Algerian independence from France in the early 1960s, political, civic and church leaders called for a referendum in Tahiti Nui.

(See: “Chronology: The French Presence in the South Pacific 1838-1990”, Julie Miles and Elaine Shaw, Greenpeace, 1990).

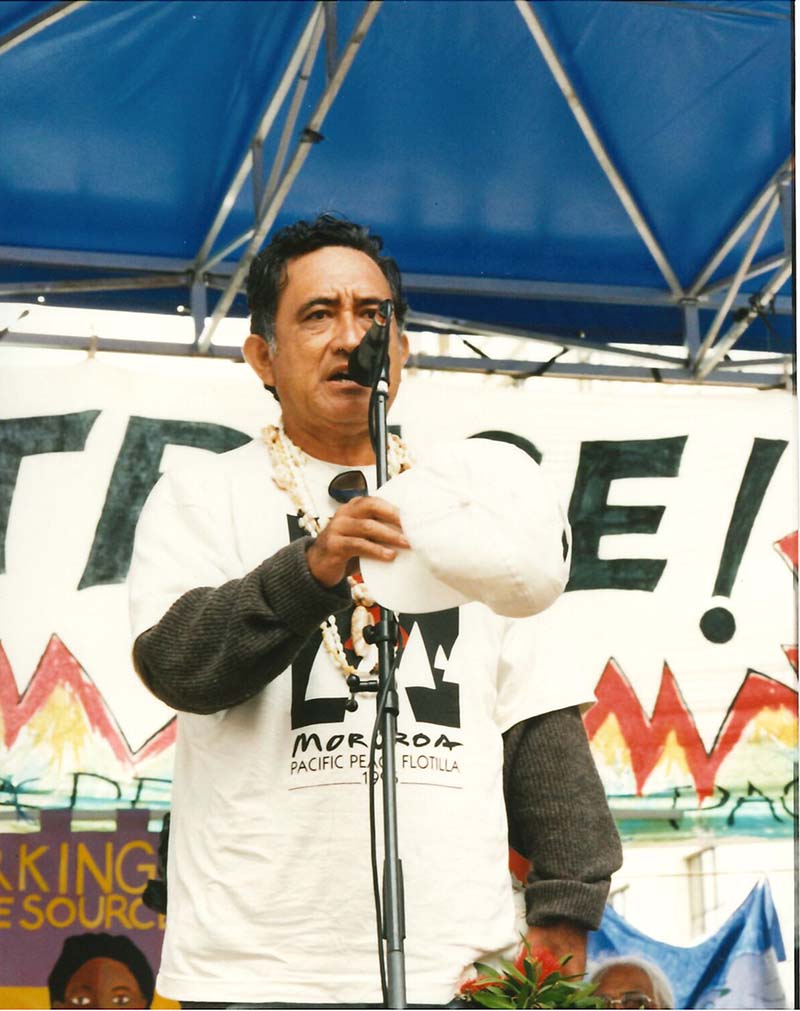

According to sources listed in Miles and Shaw (1990), the most prominent Tahitian leader at that time was Pouvana’a a O’opa (1895–1977), who led the Democratic Rally of the Tahitian People (RDPT) party. After returning to Tahiti from Europe where he had fought for the Free French forces commanded by General Charles De Gaulle in World War 2, he co-founded and led the RDPT in 1949.

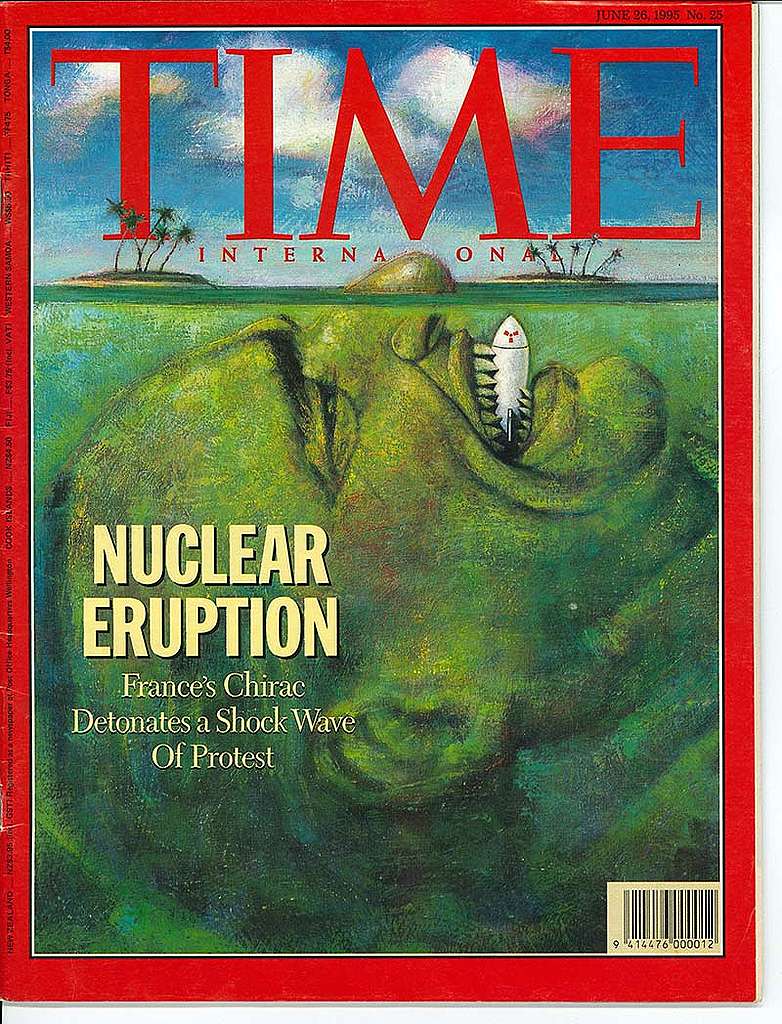

During 1950, Pouvana’a a O’opa reportedly collected signatures for the Stockholm Peace Appeal, an initiative launched by the Soviet-controlled World Peace Council on 19 March 1950, which called for nuclear weapons to be banned (See: Introduction: Resistance and Survival – The Nuclear Era in the Pacific, Nic Maclellan, The Journal of Pacific History, Volume 59, 2024. Issue 1 – Resistance and Survival – The Nuclear Era in the Pacific). Another signatory was Jacques Chirac, who would later be elected French President in 1995).

Pouvana’a a O’opa was elected as a Deputy in the French National Assembly from 1949 until 1958, when he was convicted on fabricated charges of arson and sentenced to eight years in prison and a further two years in exile in metropolitan France until 1968. His 1958 conviction was later quashed in 2018 after new evidence showed that French police had fabricated evidence or extracted it by threats of violence, and that the Governor of French Polynesia had reported his arrest to Paris before the fires had even been set. After he was pardoned in 1968, he was elected as a senator from 1971 until his death in 1977.

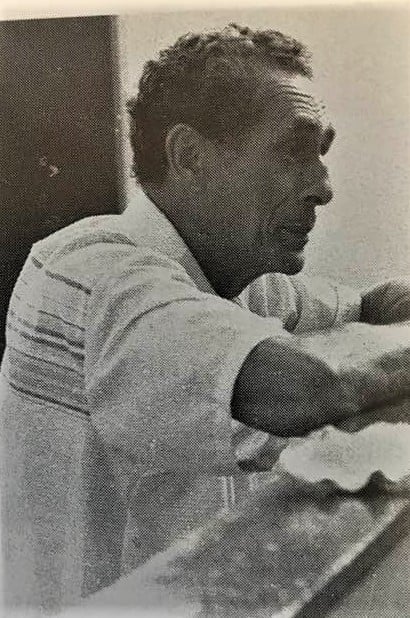

Pouvana’a a O’opa’s ally John Teariki became the leader of the RDPT in 1961, which by then was advocating for independence from France. John Teariki served as a member of the French National Assembly (FNA) from 1961 to 1967, and as a member of the Territorial Assembly (TA) of Tahiti Nui from 1957 until 1983. Both he and Pouvana’a a O’opa declared the party’s opposition to French nuclear testing before the first test at Moruroa Atoll in 1966.

In May 1963, John Teariki presented a detailed report to the Territorial Assembly (TA) in Pape’ete calling on the French government not to move its nuclear testing programme to French Polynesia.

Then in June 1963, French Foreign Legion troops arrived in Tahiti against the unanimous opposition of the TA. Pouvana’a a O’opa responded by urging the TA to demand independence. French President Charles De Gaulle responded by banning the RDPT without any consultation with the TA or the FNA and the French government re-established direct control of French Polynesia. Later that year, the French authorities ceased the regular publication of public health statistics for French Polynesia.

In January 1964, French Foreign Legion troops occupied Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls despite TA protests that the land was owned by the indigenous Mā’ohi people living on Tureia 126 km north of Moruroa Atoll and that the French military occupation of the land was illegal without any lease or title deed under law. A month later, both atolls were ceded to France via an obscure vote in the Permanent Commission of the Territorial Assembly, a small body responsible for various administrative and legislative functions that included representatives from other government bodies and advisers.

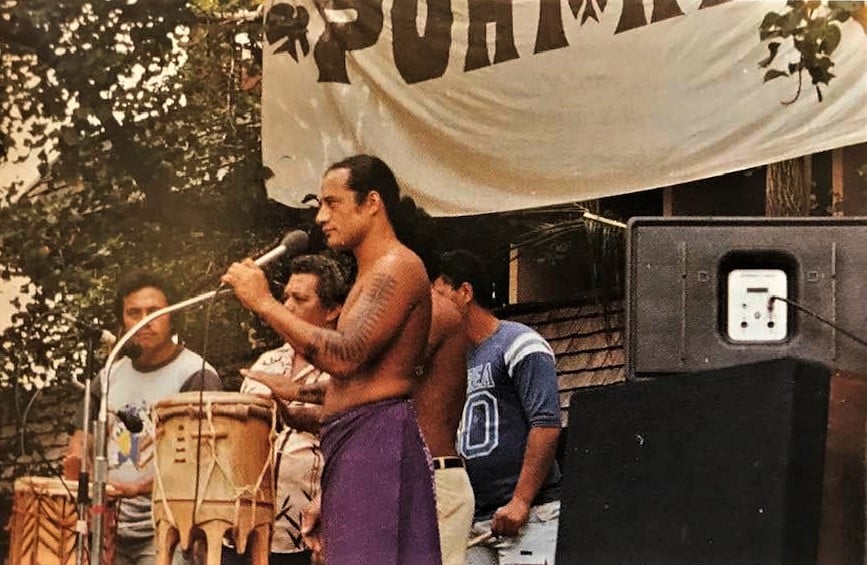

After De Gaulle banned the RDPT in 1963, John Teariki founded Te Pupu Here Ai’a Te Nunaa ia Ora (Patriotic Group for an Autonomous Polity) in 1965. The new party held its first congress on 2 July 1966, the day of the first French nuclear weapon test at Moruroa Atoll and passed a motion “to use all peaceful and legal means to end nuclear testing”.

Then in February 1965, Pouvana’a a O’opa was pardoned by President De Gaulle but refused permission to return to Tahiti for 15 years. In May, the French authorities announced the first test would take place with a ‘danger zone’ declared around it which includes seven inhabited atolls. In the TA, John Teariki stated: “If this zone is declared dangerous and prohibited for sailors and pilots throughout the world, why would it not be equally so for the inhabitants?” The authorities acknowledged their mistake and changed the radius of the zone, but Tureia remained in the danger zone and the inhabitants were not evacuated.

On 21 July, plutonium contaminated an area of Moruroa during a ‘safety-firing’ of a nuclear device (in which there is no nuclear reaction). The contaminated area was covered with bitumen in an attempt to contain the plutonium, but bitumen cannot shield radiation.

President De Gaulle visited French Polynesia on 24 September 1966 to view a 120 KT atmospheric nuclear weapon test at Moruroa Atoll from a French warship offshore. Radioactive fallout from the test reached Tureia and other islands in the Gambier Group of the Tuamotu Archipelago to the west and elevated levels of radiation were recorded in Apia, Samoa, in rainwater tanks four days later by New Zealand government scientists.

The Pupu Here Ai’a party won seven of 30 seats at the 1967 election and formed a coalition government in the Territorial Assembly with the pro-autonomy E’ai Api party led by Francis Sanford. Both parties opposed French nuclear testing.

The TA immediately expressed its opposition to the tests and strong fears for the health of the indigenous Mā’ohi people living on Tureia after the recent test. The French Governor, Aimé Grimald, responded by threatening to dismiss the TA if it continued to protest against the nuclear testing.

John Teariki, Francis Sanford and Pouvana’a a O’opa continued to call for an end to the nuclear testing and the TA urged France to allow independent scientists to investigate radioactive contamination from the nuclear tests. Neither were heeded by the French government and the tests continued.

In July 1967, some of the Mā’ohi living on Tureia moved to Tahiti where they confirmed reports that fallout shelters were being built on Mangareva, Reao and Pukarua.

In August, the Pape’ete town council adopted a strongly worded resolution once again demanding that the French authorities distribute information on the dangers of radiation, including to local news media. French Governor Grimald responded by quoting an 1879 French decree that “the municipal council cannot make any protest or petition” and declared that the Pape’ete town council had therefore committed an illegal act.

In January 1968, the TA requested that the French authorities invite three overseas scientists from Japan, New Zealand and the US and three French scientists supported by technicians from the French National Radiation Laboratory (SCPRI) to study radioactive contamination caused by the tests.

On 7 July 1968, Francis Sanford drafted a resolution in the TA calling for an end to French nuclear testing. The following month, on 24 August, his son died from leukaemia.

On the same day, France detonated a 2.6 MT thermonuclear bomb at Fangataufa Atoll followed by another similar-sized bomb at Moruroa Atoll two weeks later. Afterwards, the French authorities decided that Fangataufa was so contaminated that it was not used again as a test site for 6 years.

In November, the French government announced that the nuclear test series planned for 1969 would be cancelled due to a lack of funds. Opponents said serious radioactive contamination from the two huge August thermonuclear tests may have been the real reason.

Then on 30 November, Pouvana’a a O’opa returned to Tahiti after he was pardoned by De Gaulle, less than 6 months before De Gaulle resigned as president on 28 April 1969. Georges Pompidou was elected as the new French President on 15 June 1969, who had been prime minister under De Gaulle from 1962 to 1968. One of his ‘aides’ was a young Jacques Chirac, who would later be elected French President in May 1995.

The nuclear tests resumed on 24 June 1970 with a series of eight planned, including an experimental 1 MT hydrogen bomb. In 1971 there were five tests, including another in the 1 MT range. Following that, the governments of New Zealand, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Cook Islands, Tuvalu and Peru all protested to the French government about the tests.

The growing opposition to French nuclear testing in Tahiti Nui during the 1960s explicitly linked ending nuclear testing to ending French colonial rule. That opposition included indigenous Mā‘ohi political, civic, trade union and church leaders as well as Europeans active in those or other anti-testing organisations, such as Bengt and Marie-Thérèse Danielsson. Their book “Moruroa Mon Amour: The French Nuclear Tests in the Pacific” (Paris, 1974; New York, 1977) recounting the French nuclear testing programme and the opposition to it helped to spread awareness of the impacts of the tests, and was reprinted in an updated edition entitled “Poisoned Reign: French nuclear colonialism in the Pacific” by Penguin Books (Auckland, 1986).

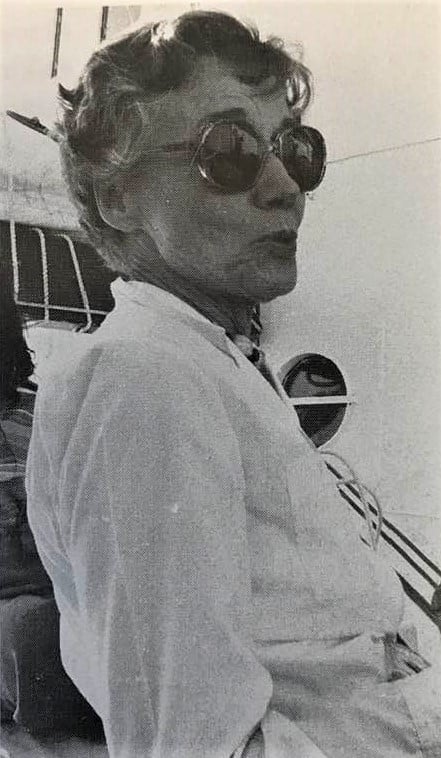

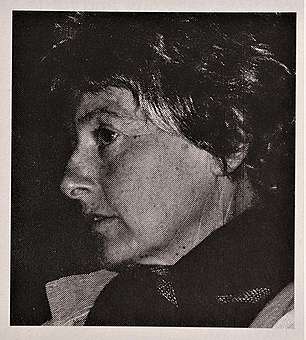

Bengt Danielsson (1921-1997) was an anthropologist, writer and a crew member on the Kon-Tiki voyage from South America to French Polynesia in 1947. He served as Swedish Consul in French Polynesia from 1961 to 1978 and was a correspondent for Pacific Islands Business magazine. Marie-Thérèse Danielsson (1924-2003) was an ethnologist and leader of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) in French Polynesia. In 1991, they were awarded the Right Livelihood Award for “exposing the tragic results of and advocating an end to French nuclear colonialism”. In their last years they moved to live in Sweden and remained active against French nuclear testing as members of the board of directors of Greenpeace Sweden. Their daughter Maruia (1952–1972) died from cancer at an early age, six years after the French nuclear tests began in Tahiti Nui.

Fiji and the origins of the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific movement

In the 1970s, Indigenous people and others around the region active in opposing the French nuclear tests started to form the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific (NFIP) movement. As in Tahiti Nui, this wider regional movement also linked nuclear testing to colonialism. When Fiji became independent in October 1970, the government in Suva became increasingly outspoken against the French tests at the same time that various civil society and church groups and community activists were mobilizing.

Walter Johnson and Sione Tupouniua (1976) have described how the ‘Against Testing on Moruroa’ (ATOM) group was founded in Fiji on 28 May 1970 by the Fiji Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), Fiji Council of Churches, and University of the South Pacific Students Association at a meeting attended by 600 people at Suva Town Hall to protest against radioactive contamination of the Pacific by French nuclear testing (See: Against French Nuclear Testing: The A.T.O.M. Committee, The Journal of Pacific History, Vol. 11, No. 4 (1976), pp. 213-216).

Fiji’s First Minister at the time, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara – soon to become the first prime minister of an independent Fiji – expressed support for the meeting and an ATOM committee was formed to carry on the protest. The new committee issued a statement pledging: “It will protest against all nuclear testing, but have a specific concern with the Pacific area, and therefore anyone who tests in the Pacific area, e.g. the French at present.”

Dimity Hawkins (2024) has described how the government of Fiji, the South Pacific Forum and civil society groups in Fiji campaigned to stop French nuclear testing (See: ‘We will not Relax our Efforts’: The Anti-Nuclear Stance of Civil Society and Government in Post-Independence Fiji”, The Journal of Pacific History, Volume 59, 2024 – Issue 1: Resistance and Survival – The Nuclear Era in the Pacific).

Hawkins (2024) reports that the first Fijian director of the Fiji YWCA (established in 1962), Amelia Rokotuivuna, later became “a pillar” of the anti-nuclear movement in Fiji.

She also identifies how the Pacific Conference of Churches (established 1966) became a strong voice against nuclear testing across the Pacific and the University of the South Pacific (USP, established 1968) was a catalyst for the development of a strong anti-nuclear testing movement in Fiji.

She reports that USP scholar Vijay Naidu, who was a leading anti-nuclear activist at the time, described the USP as, “the cradle of the regional anti-nuclear and independent Pacific movement, building the campaign against nuclear weapons testing in French Polynesia and, later, the nursery for independence and pro-democracy movements”.

In describing ATOM, Hawkins says, “Naidu explained the group’s aims were to ‘inform the Fiji public about the nuclear tests in French occupied Polynesia and also to act as a pressure-group to urge the Fijian government to take steps to stop these tests’. While it was active over a relatively short time, from formation in 1970 to gradual dissipation after 1975, ATOM played a significant role in coalescing the organizational and public voices of nuclear resistance, educating the public and engaging the newly independent government. The brief life of the group helped to build momentum on nuclear resistance in the region and actively engaged with the Fijian government.”

Hawkins also notes that key members of ATOM had scientific backgrounds, including its first president, Graham Baines, and first secretary, Suliana Siwatibau, who were both biologists at the USP. She says “… their academic approach combined with the grassroots concerns of the student, women’s, church and trade union movements created a strong platform.”

She also describes how ATOM challenged the French government’s spurious claim that the nuclear tests were not causing harm: “ATOM brought together knowledge, skills, and outreach capacity, promoting awareness of nuclear testing, instigating community meetings, education activities, and public rallies, and engaging media and politicians. Collaborations with Fijian trade unions, picketing of airline offices, petitioning the French president, and large public meetings and rallies were amongst the important actions. Much of the public education was led by science and centred on Pacific sovereignty” (Hawkins, 2024).

According to Hawkins (2024) and Johnson and Tupouniua (1976), ATOM developed a 10-point plan in 1972 which was presented to regional partners and governments, including the government of Fiji, “encompassing calls for the government of Fiji to push for greater international action through a broad swathe of actions in the UN, as well as embargoes, legal and moral support for those protesting in international waters in the region, calls for radiation data to be made available, and ‘diplomatic moves to establish a nuclear weapons free zone in all or part of the Pacific Ocean’. In the years to come, many of these elements were crucial to regional diplomatic efforts and Pacific advocacy.”

Johnson and Tupouniua (1976) also report that ATOM organised a panel discussion at the USP on the subject ‘Is a Nuclear Free Pacific Possible?’ on 13 August 1973. During a discussion, involving a Fijian senator, a representative of the Pacific Council of Churches and a student from Vanuatu attending the USP, there was a suggestion to organise a conference.

ATOM organised the first ‘Conference for a Nuclear Free Pacific’ in Fiji from 1-6 April 1975, which was attended by 90 delegates and chaired by Amelia Rokotuivuna of the YWCA (See: ‘Will to fight together’: Fiji has taken another bold step in the battle against nuclear weapons, Vanessa Griffen and Talei Luscia Mangioni, The Guardian, 8 July 2020). Dimity Hawkins (2024) gives an account of the proceedings and significance of the conference, from which the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific NFIP group emerged.

Further triennial NFIP conferences were held at Ponape in Micronesia in 1978, Hawai’i in 1980, and in Vanuatu in 1983, where a People’s Charter for a Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific was adopted.

The Charter declared: “We, the people of the Pacific have been victimised too long by foreign powers. The Western imperialistic and colonial powers invaded our defenceless region, they took over our lands and subjugated our people to their whims. This form of alien colonial, political and military domination unfortunately persists as an evil cancer in some of our native territories such as Tahiti-Polynesia, Kanaky, Australia and Aotearoa. Our environment continues to be despoiled by foreign powers developing nuclear weapons for a strategy of warfare that has no winners, no liberators and imperils the survival of all humankind.”

The next NFIP conferences were held in Manila in The Philippines in 1987 and in South Auckland in Aotearoa in 1990. These conferences advocated for a nuclear-free and independent Pacific, strengthening of the regional movement against nuclear testing, and political independence of Pacific nations.

The NFIP movement brought together indigenous peoples and others active in anti-nuclear movements from Hawai’i, Great Turtle Island (North America), Aotearoa, East Timor, West Papua, The Philippines, Tahiti Nui, Polynesia, Melanesia, South Korea and Japan.

In his introduction to the special issue of the Pacific Journal of History, entitled “Resistance and Survival – The Nuclear Era in the Pacific” (Issue 1, Volume 59, 2024), guest editor Nic Maclellan (2024) includes this brief summary: “For 20 years from the mid-1970s, there was a broad social movement for a nuclear free Pacific, as people mobilized against French nuclear testing through churches, trade unions, non-government organizations, and women’s groups. Environmental organizations such as Greenpeace were central to this movement, courageously sailing yachts and other vessels into nuclear testing zones (at great cost, with the death of Fernando Pereira in the 1985 terrorist bombing of the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior by French agents).

Within this broad campaign, however, there was also a structured movement for a Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific (NFIP), led by Pacific Islanders and Indigenous peoples from Pacific Rim countries. The NFIP movement had its own secretariat, the Pacific Concerns Resource Centre (PCRC), with a region-wide executive board. In the pre-internet age, common experiences were shared through a monthly newsletter Pacific News Bulletin and triennial conferences that determined policy and joint campaigns.”

He also lists participants at the October-November 1978 NFIP conference in Ponape in the Federated States of Micronesia as including Nelson Anjain (Republic of the Marshall Islands), Oscar Temaru and Téa Hirshon (Mā‘ohi Nui), Déwé Gorodé and Yann Céléné Uregei (Kanaky), Bernard Narokobi (Papua New Guinea), Walter Lini, Fred Timikata, and John Naupa (New Hebrides/Vanuatu), Moses Uludong (Belau/Palau), Lorine Tevi and Rev. Akuila Yabaki (Fiji), and Aboriginal activists Gary Foley, Clarrie Grogan, and Brue Walker.

In the same special issue of the Journal of Pacific History, Marco de Jong documents the roots of the NFIP movement among Māori activists in Aotearoa, detailing the work of the Auckland-based Pacific Peoples Anti-Nuclear Action Committee (PPANAC) and activists such as Hone Harawira and Hilda Halkyard-Harawira (See: ‘Our Pacific Through Native Eyes’: Māori Activism in the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific Movement, 1980–5, The Journal of Pacific History, Volume 59, 2024 – Issue 1: Resistance and Survival – The Nuclear Era in the Pacific). Maire Leadbeater’s book “Peace, Power & Politics: How New Zealand became nuclear free” (2013, Otago University Press:) also includes a chapter on the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific movement.

Greenpeace delegates to the NFIP conferences included Kay Couper in 1975, Elaine Shaw in 1980, and Bunny McDiarmid in 1987 and 1990.

Maclellan emphasises how the articles in the special issue of the Pacific Journal of History reflected, “the renewed focus on documenting Islander responses to the Cold War testing programmes by the Western powers. Echoing the contemporary call from Pacific climate justice activists (‘we are not drowning, we are fighting!’), they highlight examples of local, regional, and North–South resistance to nuclear weapons by Pacific Islanders. While based on longstanding practices of archival research, they draw on creative and artistic expressions of multidisciplinary approaches and interrogate the historian’s role.”

He identifies the following significant themes highlighted by the articles in it:

- Protests by Pacific Islanders against nuclear testing began in the 1950s, pre-dating the rise of the wider NFIP movement in the 1970s;

- Fiji’s early foreign policy and the formation of the South Pacific Forum in 1971 involved significant advocacy against French nuclear testing;

- The role of culture and identity was central to Pacific anti-nuclear activism, amplified through song, poetry, graphic design, and community theatre as well as the written word;

- The NFIP movement played a critical role linking local struggles to the wider regional context, through pan-Pacific, Indigenous-led activism around self-determination and decolonization;

- The connections between the NFIP movement and solidarity movements in the Global North, at a time of Cold War nuclear build-up, carried Islander perspectives into global debates – echoing contemporary climate justice initiatives.

He also describes how, “Throughout the 1950s, customary leaders and intellectuals from Fiji, Cook Islands, Marshall Islands, Samoa, and other colonial dependencies combined to speak out against the US and British nuclear programmes, petitioning the United Nations for an end to nuclear testing. … The special issue also includes a striking example of these petitions to the United Nations Trusteeship Council. The petition, inspired by the March 1954 Bravo atmospheric nuclear test on Bikini Atoll, was prepared by customary iroij (chiefs), local businessmen, and schoolteachers in the Marshall Islands. It requested that ‘all experiments with lethal weapons in this area be immediately ceased’.”

The special issue reproduces the 20 April 1954 Marshall Islands petition: MANUSCRIPT XLIII: Petition to the United Nations Trusteeship Council from the Marshallese People, 20 April 1954, Nic Maclellan: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00223344.2023.2285475#abstract

The main requests in the petition were as follows:

* All the experiments with lethal weapons within this area be immediately ceased.

* If the experiments with said weapons should be judged absolutely necessary for the eventual well being of all the people of this world [Page 3] and cannot be stopped or changed to other areas due to the unavailability of other locations, we then submit the following suggestions:

- All possible precautionary measures be taken before such weapons are exploded. All human beings and their valuable possessions be transported to safe distances first, before such explosions occur.

- All the people living in this area be instructed in safety measures. The people of Rongelab would have avoided much danger if they had known not to drink the waters on their home island after the radio-active dusts had settled on them.

- Adequate funds be set aside to pay for the possessions of the people in case they will have to be moved from their homes. This will include lands, houses and whatever possessions they cannot take with them, so that the unsatisfactory arrangements for the Bikinians and Eniwetak people shall not be repeated.

- Courses be taught to Marshallese Medical Practitioners and Health-Aides which will be useful in the detecting of and the circumventing of preventable dangers.

Greenpeace and the Moruroa peace flotilla protests of the 1970s

As opposition to French nuclear testing continued to grow around the region, a grassroots network started mobilising in support of the first anti-nuclear testing protest yacht to sail from Aotearoa to disrupt the French government’s nuclear weapons testing at Moruroa Atoll.

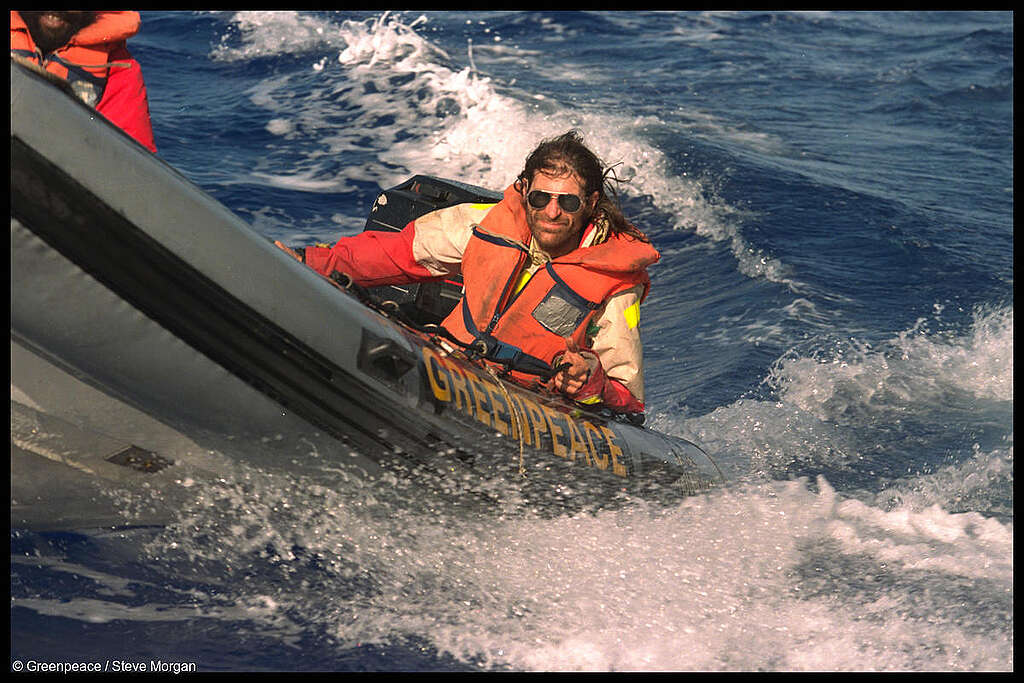

Greenpeace III (originally named Vega) departed from Auckland on 17 April 1972 sailed by skipper David McTaggart and crew members Anna Horne, Nigel Ingram and Ben Metcalfe, A Canadian who represented the new Greenpeace Foundation that had been set up in Vancouver in 1971 to oppose US nuclear testing at Amchitka in the Aleutian Islands of Alaska (which was previously known as the ‘Don’t Make a Wave Committee’).

Two months after Greenpeace III departed for Moruroa, three more small yachts formed a flotilla to join them off Moruroa, assembled and supported by New Zealand CND, Peace Media and a loose network of students and individuals opposed to the tests. The NZ flotilla included Tamure, Boy Roel and Magic Isle, although for various reasons these other small yachts did not make it to Moruroa.

Greenpeace III arrived off Moruroa Atoll and then entered the exclusion zone set up by the French authorities on 1 June. Shortly after that on 13 June the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, Sweden, condemned French nuclear testing and adopted a declaration calling for the elimination of nuclear weapons.

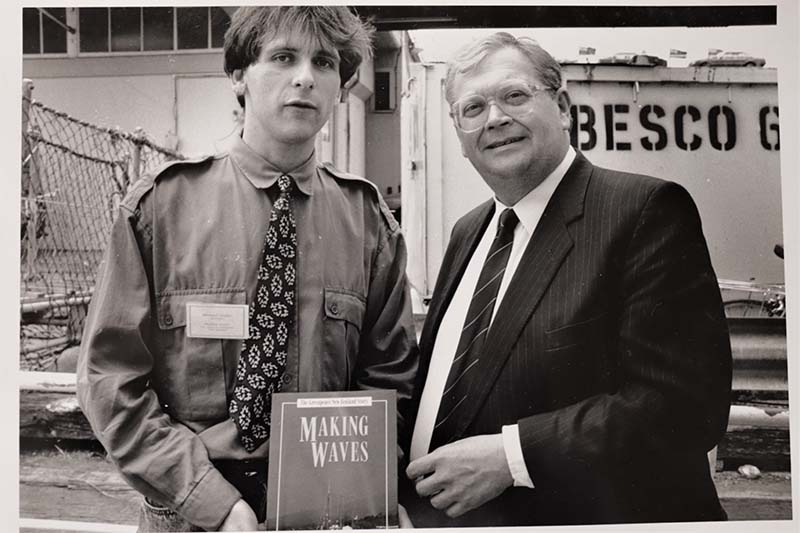

On 1 July, Greenpeace III was rammed and seized by a French warship and towed to Moruroa Atoll. Further details of the early protest voyages from Aotearoa to Moruroa are contained in Making Waves – the Greenpeace New Zealand Story 1971 – 1990 (Michael Szabo, Reed Books, 1991).

On 25 November 1972, both the New Zealand and Australian governments brought cases against French nuclear testing to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, requesting the Court issue an interim injunction against the French tests going ahead while the case proceeded. They were later joined by the government of Fiji in May 1973.

As Hawkins (2024) points out, Fiji was the only Pacific Island state to make formal interventions in each of the cases, and submitted evidence of the harm the tests were doing across the region. The application also listed Fiji’s formal protests and other actions taken, including direct pleas to the French government, speeches at the United Nations General Assembly, the South Pacific Forum condemning French nuclear testing, objections raised in other UN forums and at Commonwealth Heads of Government Meetings. The application also noted the government of Fiji had imposed bans, “on the landing and overflight by French military aircraft and on calls by French naval vessels which might be connected with the tests” and that “Fiji public opinion has also voiced its strong opposition to the continuation by France of its testing programme.”

In May 1973, Pouvana’a a O’opa and Francis Sanford sent an open letter to 200 newspapers in metropolitan France calling for the tests to end. Only one newspaper published it (L’Express), owned by anti-nuclear testing French politician Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber. In response he called for the formation of a ‘Bataillon de la Paix’ to travel to Tahiti to join the opposition to the tests, including former French army general Jacques Pâris de Bollardiere.

Two of the main French trade unions representing three million workers also supported the protest and there were anti-testing protests in Paris, Toulouse and Montpelier. In Paris the police baton-charged the demonstrators to break them up and anti-nuclear marchers were prevented from crossing the border from Belgium into France by French authorities (Miles and Shaw, 1990).

On 24 May 1973, 82 nations including Britain and the Soviet Union voted for a World Health Organization (WHO) resolution in Geneva deploring all atmospheric nuclear tests (at the time China was also conducting atmospheric nuclear tests at Lop Nor in Xin Jiang Province, in the west of China).

In Australia, trade unions refused to unload French imports and a thousand bags of post from France piled up in transit there. In Britain, the Trade Union Congress called an all-union boycott of commerce and communications with France from 1-7 July 1973.

A second larger anti-testing flotilla was organised which sailed from Aotearoa to Moruroa in May-June 1973, including Fri, crewed by David Moodie, Martini Gotje, Rien Achterberg, Rua Paul, Naomi Peterson, Ted Rutter and others, as well as Greenpeace III, once again crewed by David McTaggart and Anna Horne plus Nigel Ingram and Mary Lornie. The other yachts that sailed from Aotearoa were Spirit of Peace, Bluenose, Barbary, Arakiwa, and Tanea.

The Fri’s 1973 voyage is documented in the book ‘Fri Alert’ (1974, editor Elsa Caron) and the documentary film directed by Alister Barry, ‘Mururoa 1973’.

More protest yachts were set to sail to Moruroa from around the region, including Bluenose, Arakiwa and Tanea from Tauranga; two other boats from Wellington and Christchurch; Malaguena, Warana and La Flor from Australia; Carmen from Tahiti, and others from Fiji, Samoa and Peru. Only Fri, Vega and Spirit of Peace were able to make it as far as Moruroa. Three decades later it emerged that the French military had sabotaged some of the early protest yachts before their planned departures (See: “Tale of ineptitude and machismo”, Catherine Field, NZ Herald, 1 July 2005).

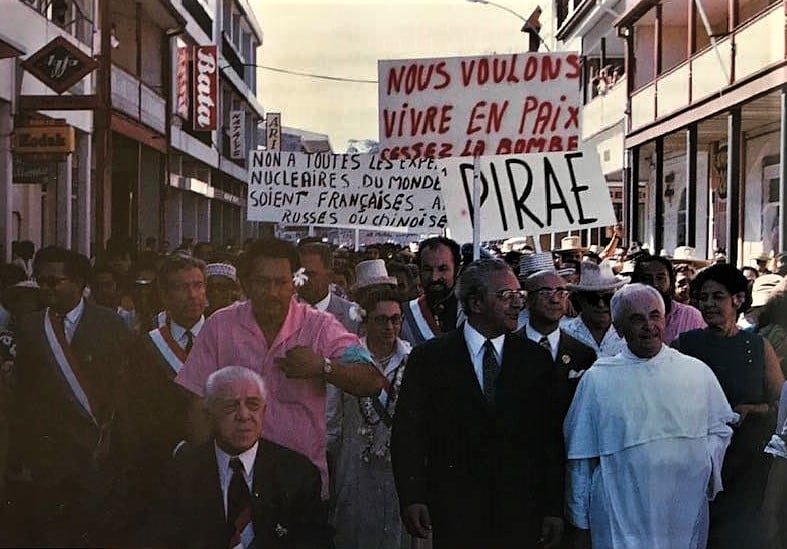

In Pape’ete, over 5,000 people rallied against nuclear testing on 23 June 1973, the biggest rally there to date which included Pouvana’a a Oopa, Francis Sanford and six members of the ‘Bataillon de la Paix’.

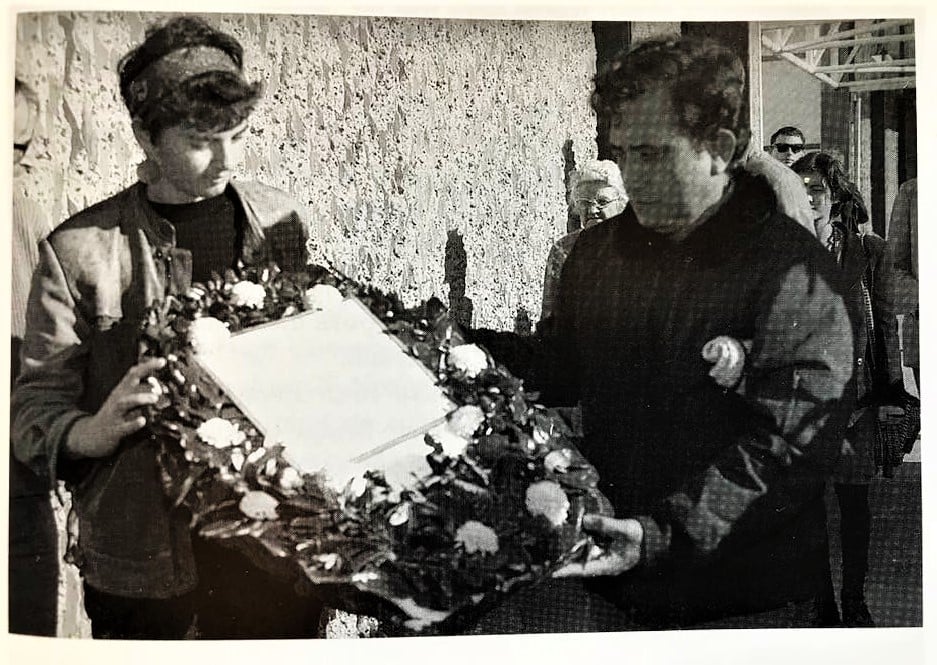

On 23 June 1973, Pouvana’a a Oopa (front centre), Francis Sanford (right of Pouvana‘a wearing suit jacket) and Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber (second from left with sash) marching against French nuclear testing, Pape’ete, Tahiti. Photo by Bengt Danielsson.

The New Zealand government led by Labour Prime Minister Norman Kirk sent messages to 100 countries to mobilise support for the protest. The same day the ICJ urged France to avoid conducting any nuclear tests that caused radioactive fallout to reach the territories of New Zealand and Australia.

After France ignored the ICJ’s interim injunction against the tests, NZ Prime Minister Norman Kirk ordered the navy frigate HMNZS Otago to Moruroa to officially protest against the nuclear tests, which was later relieved by HMNZS Canterbury. Shortly after that, Australia and Peru recalled their ambassadors from France in protest, and then Peru broke off diplomatic relations with France.

On 15 August 1973, French commandos boarded Greenpeace III, assaulting skipper David McTaggart and injuring one of his eyes, prompting the NZ government to deliver a formal protest to France.

Then in April 1974, French President Pompidou died and a new presidential election was called. Valéry Giscard d’Estaing won the election on 20 May, polling 50.8% of the vote, narrowly defeating the Socialist Party candidate Francois Mitterrand. He came from the conservative side of French politics but was relatively more liberal compared to De Gaulle and Pompidou, and as a former senior civil servant he was seen as part of a new generation of ‘technocrats’.

On 8 June 1974, the new President Giscard d’Estaing announced that after a series of eight nuclear tests that year, from 1975 all French tests would be conducted underground at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls.

Opposition to the French nuclear tests from within Tahiti Nui and the wider region, the protest flotillas of 1972 and 1973, the legal cases taken to the International Court of Justice, protests within metropolitan France, and growing regional and international diplomatic pressure undoubtedly all played a large part in the decision by the French government to end the atmospheric nuclear tests. However, moving them inside Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls into shafts drilled down through the coral into the underlying rock including below the waters of the turquoise lagoons was not a genuine solution to the problem of radioactive contamination.

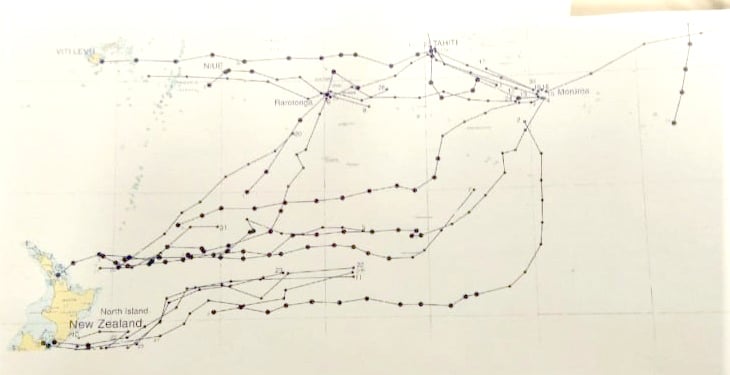

Encouraged by the end of French testing in the atmosphere, on 11 August 1974, coordinated by the newly incorporated Greenpeace New Zealand, Fri embarked on an epic three-year 40,000km “Pacific Peace Odyssey” from Aotearoa, carrying the anti-testing Nuclear Free message to all of the nuclear weapons states.