Te Mana o te Wai is an approach to looking after freshwater bodies like rivers and streams. It’s a world-leading policy framework that aims to restore and preserve the balance between the environment, people and the use of water.

Te Mana o te Wai ensures the health and well-being of the water is protected and human health needs are provided for before enabling other uses of water.

However the Government now wants to ditch this protection.

Table of contents

- The life force of water

- Te Mana o te Wai in the regulations

- Te Mana o te Wai in practice

- Human activities are currently degrading the rivers of Aotearoa

- The need for sustainable water management in Hawkes Bay

- Better regulation works for healthy rivers

- Bringing people together

- Let’s recognise the many opportunities of Te Mana o te Wai

- Timeline of Te Mana o te Wai

The life force of water

Wai (water) is essential for life. For the wild animals that live in the streams, wetlands and rivers. And for people who need it for drinking, eating and cleaning.

Rivers and streams sustain more than just life. For generations the people living around a water body have relied on it for food, to swim, and to live well. When the water is gone, the way of life goes too.

Most people in New Zealand deeply care about the health of the rivers and have a special connection with fresh water. Most of us know streams, rivers, and watery places that are important to us. We visit places of such pure water as Rotomairewhenua, the Blue Lake or Te Waikoropupu Springs to refresh our spirits.

The concept of ‘te mana o te wai’ recognises the power and significance of water to all life, its life force, the integrity of a river. Te mana o te wai recognises and aims to protect the mauri, the life force of water. It recognises the river or spring has a right to be, for its own sake.

In te Ao Māori, a river is often regarded as atua or tupuna, and oftentimes given personhood. In a pepeha, by which Māori introduce themselves, rivers – and mountains, ocean, creatures and the land itself – are identifying parts of their whakapapa or lineage. These are reciprocal relationships of mutual care and guardianship.

This Māori worldview can lead us to treat the land and water with the respect we give our family. As a concept te mana o te wai signifies the respect we should give the water that gives us life.

Te Mana o te Wai in the regulations

In 2014 the Government of the time placed Te Mana o Te Wai within the National Policy Statement for Fresh Water. Te Mana o te Wai would be a consideration when authorities were deciding whether or not to allow developments to go ahead.

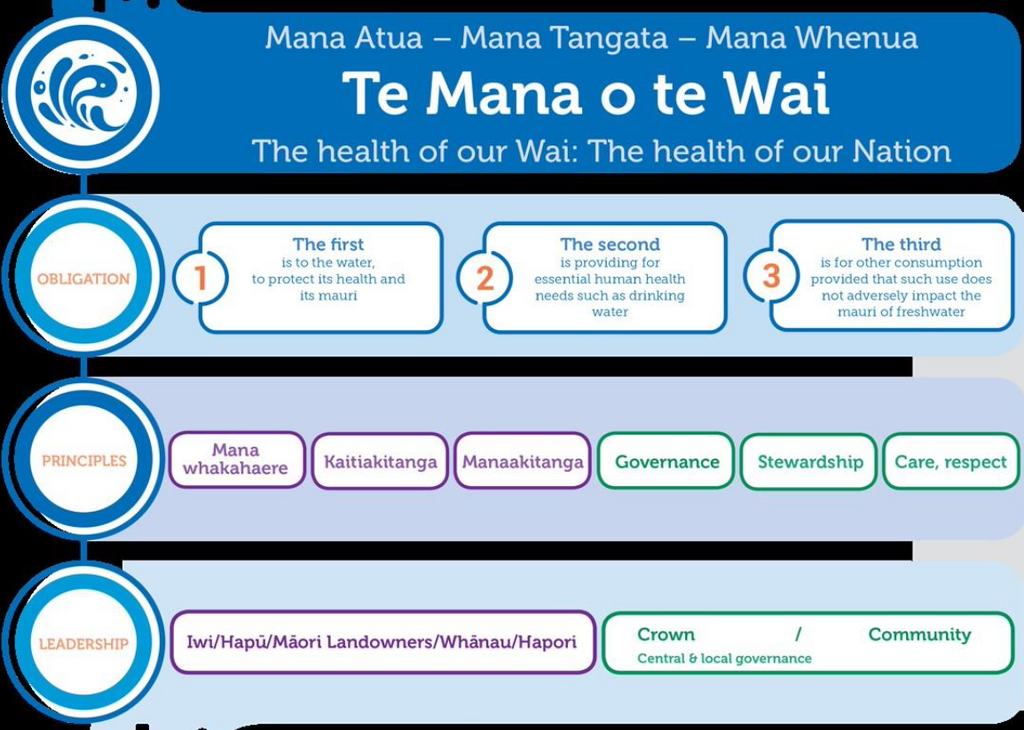

Te Mana o te Wai sets a simple order of priorities. It states that:

- authorities must consider the health of the freshwater ecosystems before any proposed development.

- Secondly, authorities must consider people’s ability to access healthy water – for example, their access to safe drinking water.

- Finally, other uses of water are considered, including commercial and business interests if the first two priorities have been met.

Te Mana o Te Wai is a world-leading policy because it prioritises the health of water in and of itself above all other uses of water. It also recognises people’s connection to water.

The National Policy Statement sets out that in consultation with the communities and iwi, councils must set long-term visions, goals and values with timeframes for improving health of the defined water bodies. For example, ecosystem health is one of the five compulsory values, and drinking water supply is one of the nine other values.

Te Mana o Te Wai is a crucial part of the National Policy Statement to improve the health of water bodies for the generations to come. It’s one of the only protections that exist in Aotearoa that could stop the pollution of water bodies, drinking water, and rivers at the source.

Now, in 2024 the Government is proposing to remove this protection, saying commercial entities no longer have to comply with Te Mana o Te Wai while they review the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management.

The Government wants to turn Te Mana o te Wai on its head – to favour economic uses above the life-supporting capacity of water.

Te Mana o te Wai in practice

💧 When managing fresh water Te Mana o te Wai ensures the health and well-being of the water is protected. If the river is healthy, the wildlife, the threatened tuna (eels) and many native birds, will thrive.

Taking into account the needs of a river can also mean providing for a water body to express its natural form and character. This could be by moving within its bed or changing course.

🚰 If the river is healthy then people are healthy. People who live near the river can swim and collect food. It means councils can source clean drinking water for the population.

We call the waterbody that drinking water is drawn from, such as a lake, river or aquifer, ‘source water’. Water sources are often underground and collect water over decades from many different water bodies.

🚰💧 If the river is healthy and people are healthy then Te Mana o te Wai allows other uses, such as irrigation. These other uses also need to give benefit and create wellbeing, which may be economic. Commercial use must be sustainable and safeguard the life-supporting capacity of the water.

Te Mana o te Wai as a policy, aims to restore and preserve the balance between the water, the wider environment, and the community. This ‘balance’ isn’t intended to signal a trade-off between Te Mana o te Wai and other goals. It emphasises that healthy fresh water is a prerequisite for a healthy wider environment and community.

Te Mana o Te Wai does not give final say, or assign decision-making over fresh water decisions to anyone; but it does say to include the community and mana whenua, the people of that area, in decision-making.

| “Te Mana o te Wai, principally, is about lifting that standard for how we care for fresh water. And recognising that first priority being about ensuring the life-supporting capacity of water. So that’s things like protecting wetlands, ensuring fish passage up and down catchments. Ensuring that practice on-farm is improving. Being more conscious in our decision-making with regards to fresh water, and putting the water first.” Dr Mahina-a-rangi Baker, Environmental Planner |

Human activities are currently degrading the rivers of Aotearoa

Protections such as Te Mana o te Wai are sorely needed. Human activities are degrading waterways. This is risking many of the things we value, such as native wildlife and being able to swim and collect food.

Most of New Zealand’s indigenous freshwater fish species are at risk of becoming threatened with extinction. About two-thirds of freshwater native bird species are classified as at risk. This includes some taonga (treasured) species such as longfin eels (tuna). Tuna are at risk of becoming just a memory – they’re already gone in some places.

- Follow the life journey of tuna, and explore the challenges facing them, nature and us: Story map of tuna

The most pervasive contaminant of groundwater is nitrate. This is caused by too much synthetic nitrogen fertiliser use in agriculture. Increased nitrate in rivers leads to algae and cyanobacteria growth, which can kill off freshwater fish and invertebrates.

Nitrate in drinking water is a risk to human health. Nitrate contamination of drinking water is being measured above official recommendations across New Zealand.

- Know your nitrate – Interactive nitrate map

Pollution from wastewater overflows and livestock runoff can make swimming and paddling unsafe. Water sports can be unsafe if rivers and lakes are contaminated.

It’s estimated 45% of Aotearoa New Zealand’s total river length is not suitable for activities like swimming.

In the context of the bigger challenge of the climate crisis, healthy water ecosystems such as wetlands have a vital rebalancing role.

| “The problem we have currently is that the fresh water management system in New Zealand encourages the opposite. So it says how much water can you take out of the system before it dies and then we’ll use all of it.” Tina Porou, Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāi Tāmanuhiri, MNZM |

The need for sustainable water management in Hawkes Bay

The plains of Hawkes Bay were created by a series of river systems coming down from the ranges, which still exist underground. Ngaio Tiuka is Ngāti Kahungunu’s Director of Environment and Natural Resource Unit. Ngaio remembers as a child jumping into streams that now no longer have water because there are too many consents to take too much water.

Under Te Mana o te Wai councils need to reduce water takes to within sustainable limits. Yet commercial interests in Hawkes Bay want to take more water from even deeper underground. Residents are organising to stop this industrial water storage scheme which would come at the expense of wai.

Better regulation works for healthy rivers

The requirement to give effect to Te Mana o te Wai is set nationally, but it’s applied locally.

Even if the present Government removed Te Mana o te Wai from the National Policy Statement for Freshwater, anyone can use this framework, the regional and district councils, and also community groups.

For example Taranaki Regional Council has said it wants to commit to Te Mana o te Wai in its own new Freshwater Plan in order to turn around declining water quality in their region.

| “We can also view this as an opportunity to lift up the helicopter and create a vision for our district where we work together with other groups to drive the improvement of all of the waterways which run through our catchment.” Paul Reese, environmental manager |

Bringing people together

By using the framework provided by Te Mana o te Wai, councils, landowners, water sportspeople, mana whenua, fisherpeople, families, and scientists, can come together to care for their freshwater environments. They can observe what’s happening, measure, reduce impacts and help restore the environment.

According to New Zealand common law no one owns freshwater. When all local people feel responsibility for the rivers and can give input into the solutions it can lead to better outcomes. Better regulation will be informed by the community. Rivers will thrive when the people around them care for them.

Te Mana o Te Wai asks authorities to actively involve tangata whenua in decisions that maintain, protect, and sustain the health and well-being of freshwater. Mana whenua are kaitiaki who have responsibility through whakapapa. And as with any vital stakeholder, Māori must be part of the conversations and decision making.

| With your food basket and my food basket, the people will thrive. Nā tō rourou, nā taku rourou ka ora ai te iwi. Whakataukī |

Let’s recognise the many opportunities of Te Mana o te Wai

Te Mana o te Wai recognises the interconnectedness of ecosystems, and the interconnectedness of people. A lot of us share a connection to the place we grew up, or presently live, where we feel we belong. Te Mana o te Wai helps us to recognise the responsibility to look after that place we feel connected to.

Te Mana o te Wai provides the opportunity to incorporate the wisdom of matauranga Māori in policy and decision making. It’s a framework already in place that allows everyone to connect together to contribute solutions.

Mauri is not defined in the National Policy Statement for Freshwater. But it’s a concept that should help guide our decision making. It speaks both to the life energy that flows through all things and the interconnectedness of all things. When the mauri of the freshwater environment is negatively affected this can affect the cultural, spiritual, and physical wellbeing of communities.

Modern science has been moving over years more towards an ecosystems view, rather than trying to save single species alone. If we change a habitat so much that a species is lost, it will have many knock on effects in that ecosystem.

By bringing together the knowledge gained over generations we can have informed, consensus-based decision-making so that all can thrive.

| “There is more and more recognition … matauranga Māori, or traditional Māori knowledge, has a lot to teach us and if you can take the best of that system and the best of the Western science system, if you like, the cross pollination or collaboration between those things is really powerful.” Riki Ellison, Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Toa Rangatira, Te Āti Awa, Environmental management |

Timeline of Te Mana o te Wai

| 2011 | The Government creates the first freshwater national policy statement (NPS-FM) |

| 2014 | Te Mana o te Wai has been part of the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (NPS-FM) since 2014. This NPS-FM recognised the national significance of Te Mana o te Wai by recognising a variety of related values. It provides national direction which regional councils translate into action on the ground through their regional policy statement and regional plans and city and district councils through their district plans. |

| 2016 | A severe campylobacteriosis outbreak spread by water in Havelock North led to over six thousand people sick, 42 hospitalised, and four people died. |

| 2017 | The Government established a formal inquiry into the Havelock North campylobacteriosis outbreak which reported on what went wrong and lessons for the future. |

| 2017 | Amendments made to the NPS-FM set out an intention to put the health and well-being of freshwater bodies at “the forefront of discussions and decisions about freshwater”. An objective and policy were added at that time requiring councils to ‘recognise and consider’ Te Mana o te Wai. |

| 2017 | River quality, swimmable rivers and freshwater use was one of the top issues people voted on in the general election. |

| 2018 | The new Government announced policy changes to strengthen the protection of source water and improve the country’s drinking water supply system. Three expert panels are set up to advise the Ministry for the Environment on water policy: Kahui Wai Māori, the Science and Technical Advisory Group, and the Freshwater Leaders Group. |

| 2020 | The NPS-FM 2020 was updated to require regional councils to prioritise the protection of drinking water sources over commercial interests using Te Mana o te Wai framework. The NPS-FM 2020 recognises that degraded waterways are not able to supply good quality water for drinking. Te Mana o te Wai says that the health and well-being of freshwater is at the centre of all management decisions, working towards restoring and protecting the mauri of freshwater. NPS-FM 2020 has a single objective and 15 policies which must be implemented by changes to regional policy statements and plans. In consultation with the communities and iwi, councils must set long-term visions, goals and values with timeframes for improving health of the defined water bodies. For example, ecosystem health is one of the five compulsory values, and drinking water supply is one of the nine other values. |

| 2022 | Kahui Wai Māori reported back to the Minister for the Environment. |

| 2023 | The newly elected coalition Government signalled its intention to rewrite the RMA to reprioritise the ‘enjoyment of property rights’. |

| Feb 2024 | 50 freshwater experts and leaders called in an Open Letter to the Prime Minister and Ministers to retain the NPS-FM 2020 and make no changes to Te Mana o te Wai. |

| April 2024 | The Government announced it would disapply Te Mana o te Wai from consenting decisions through an amendment to the Resource Management Act. |