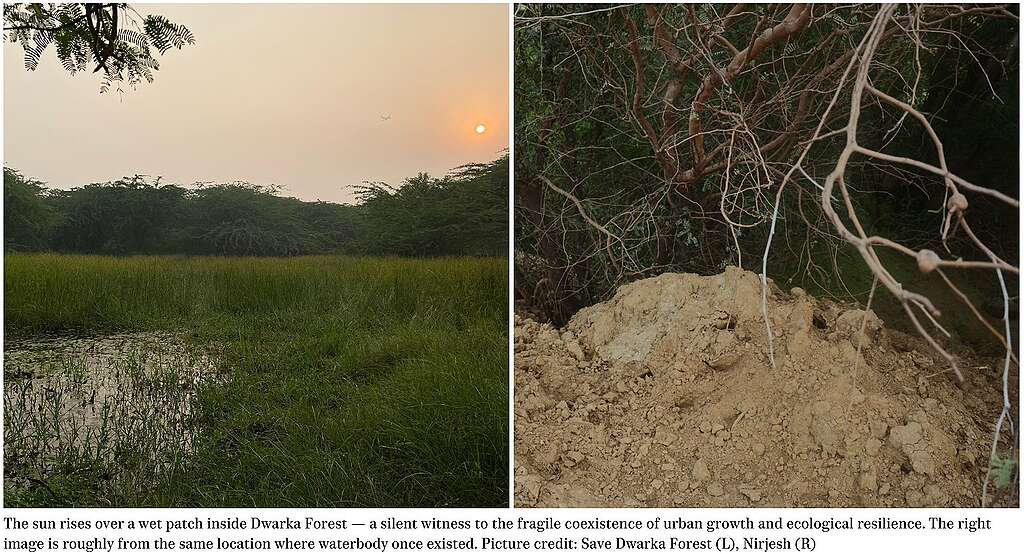

Dwarka Forest has long stood as one of Delhi’s unique stretches of nature. Unique in the sense that this particular patch is not a remnant of some sacred grove, protected site, or archaeological monument, but something fresh and novel, building itself upon the city’s refuse. Dwarka Forest is a mosaic of native and invasive trees, scrubland, grass patches and water bodies, lying just beside the T3 terminal. If you have ever arrived in Delhi by air, chances are you have seen this patch of forest just before your plane touched down. Dwarka Forest is stubbornly wild, offering refuge to over 65 species of birds and herds of Nilgai, the largest Asian antelope.

Fragmented by development and ignored in official city plans, our forest has long been under siege. Today, it faces a new and urgent crisis: contractors working on this land have fenced off large parts of the forest, disrupting natural animal movement. In the intense 40-degree heat of Delhi’s summer, the Nilgai (a Schedule II animal) are now trapped inside fenced plots, without easy access to water sources. This inhumane obstruction of their paths, combined with extreme heat, is pushing these animals toward suffering—and possibly a slow death.

Section 9 of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 (Last Updated 1-4-2023), prohibits the hunting of any wild animal listed under Schedules I and II, except as provided under Sections 11 and 12. Further, clause (b) of sub-section (1) of Section 11 qualifies exceptions only when the species has become dangerous to human life or property or is so disabled or diseased as to be beyond recovery. The Act does not include negligence by the Forest Department as a valid qualification.

This is not just an environmental issue; it is also a moral failure on the part of multiple stakeholders. The Ministry of Railways, for neglecting this land for decades after acquiring it — letting it rot as a dumping ground until nature reclaimed it. The Rail Land Development Authority, for trying to erase that resilience through illegal tree felling and construction, prioritising infrastructure over life. The Forest Department, for only acting after relentless citizen pressure, despite clear signs of ecological harm. The National Green Tribunal, for stripping the forest of protection — not by assessing its ecological value, but by questioning its legal classification. The private contractors, Bagmane Builders who fenced in wild animals during a deadly heatwave without accountability. And every authority that has looked the other way — complicit not just in ecological destruction, but in the slow violence of inaction.

Thanks to relentless citizen action, Dwarka Forest has been kept alive till now. Residents, environmental groups, and few concerned citizens have fought hard to get a stay order against construction activities. Their collective efforts have bought time for the forest. But the battle is not yet won. The forest still awaits legal recognition. And now, while the legal process is still underway, authorities that should be protecting the forest are allowing harmful interventions like fencing to go unchecked. Their inaction is not ignorance, it is a conscious choice.

We are watching, in real-time, what happens when nature is enclosed, divided, and denied its basic needs, all under the illusion of ‘development’. A petition has been launched demanding two basic requirements: the removal of fencing to restore free animal movement and provision of regular water points inside the forest during peak summer.

The fencing must be removed. Water supply must be ensured.

By signing the petition below, you stand with Delhi’s Forest, with the lives of the Nilgai, and with the idea that urban nature matters. Sign the petition. Share it widely. Let’s stand in solidarity and amplify the voice of our beautiful forest. The forest has stood for us, it’s time we stand for it.

Note: The original version of this piece was self-published on Youth Ki Awaaz here.

Author

Nirjesh Gautam is a researcher at the Centre for Urban Ecology and Sustainability, Ambedkar University Delhi. His current work focuses on the ecological role and impact of non-native tree species in urban landscapes.

References:

- The Wire. (2023, July 15). Dwarka forest and how we underestimate urban biodiversity. The Wire. https://thewire.in/environment/dwarka-forest-and-how-we-underestimate-urban-biodiversity

- Mathur, N. (2023, June 27). When rewilding urban ecosystems, ask what an invasive species is. The Wire Science. https://science.thewire.in/environment/when-rewilding-urban-ecosystems-ask-what-an-invasive-species-is/

- Indian Parliament. (1972). The Wild Life (Protection) Act, 1972. Ministry of Law and Justice. https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/1726/1/a1972-53.pdf

- Scroll Staff. (2023, July 2). How one man is battling to save the Dwarka forest in Delhi. Scroll.in. https://scroll.in/article/1079856/how-one-man-is-battling-to-save-the-dwarka-forest-in-delhi