In 1961, when I was 14, working on a science fair project, my father – a geologist and petroleum engineer – explained oil depletion to me. To grow production, oil companies were drilling deeper and deeper wells, developing technologies to extract more oil from spent fields, and would one day tap into shale rock and the Canadian tar sands to extract the dregs.

Oil, he explained, was a finite store of condensed organic matter from the bottoms of ancient seas. The industry had been extracting the highest quality and least expensive oil, but over time, the quality of oil would decline, the cost of finding it would increase, and decades in the future, perhaps in my lifetime, oil would no longer be economic to produce.

Although we would not technically see the end of all oil on Earth, the cost/benefit ratio would begin to favour other forms of energy. He told me then, in 1961, that oil companies should be developing other energy sources, that they should consider themselves in the “energy business,” not just the oil business.

Since my father knew all this 60 years ago, I suspect that virtually every engineer and manager in the oil industry knew the same facts. They knew oil was a finite resource, and would eventually run out. They also knew that burning oil created carbon emissions, which would heat the planet. In 1965, the American Petroleum Institute warned that CO2 pollution could “cause marked changes in climate” with “catastrophic consequence.”

Now, 60 years later, all these events have come to pass. The year of peak oil discoveries is behind us (1962), the peak of conventional oil production is behind us (2005), most major oil fields are in decline, oil quality and net energy are in decline, extraction costs are rising, oil companies have gone after the dregs in shale rock and tar sands, and – no surprise to anyone – carbon emissions are heating the planet to catastrophic effect.

On March 8th this year, Saudi Arabia slashed oil prices after Russia refused to cut production in response to the Coronavirus economic recession. Saudi Arabia threatened to increase production which will lower prices and undermine both Russian and American companies. However, this bluster is actually a minor tantrum in a larger story: The natural decline of global oil production.

Denial and data

We live in the era of peak oil, but just as the modern oil industry attempts to deny the effects of carbon emissions, the industry has also found it convenient to deny that oil is a finite resource that will peak and decline. Since 1956, when Shell geophysicist Marion King Hubbert predicted (accurately) the peak of US conventional oil, industry cheerleaders have mocked anyone who dares to speak about the natural peak and decline of oil.

Last year, the International Energy Agency claimed that, “The United States is increasingly leading the expansion in global oil supplies,” and promised that a “second wave of the US shale revolution is coming.” Forbes magazine, a relentless denier of oil limits, stated in 2017 that “Peak oil is not in sight,” and that any impact of limits on energy policy or production “will not be a force for some time.” This sort of bravado bolsters oil company stock prices, but ignores geo-physical reality.

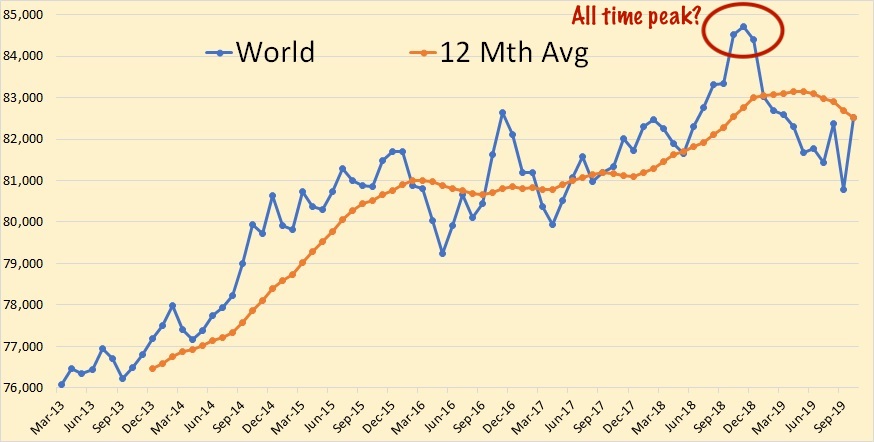

Although the natural peak and decline of oil remains inevitable, we won’t know the precise moment of maximum oil production until a few years after the event. However, recent production data suggests that the all-time peak production may have already occurred. Ron Patterson, a computer engineer, who worked with Saudi Aramco oil company, suggests that the all-time peak may prove to be November 2018, when the world was producing oil at a rate of 84.7 million barrels per day (mb/d). Production has declined ever since, and with the Coronavirus pandemic slowing economies everywhere, production may never recover.

I recall my father estimating that the peak might be around 90 mb/d, which now looks close, perhaps slightly optimistic. About half of global oil production depends on the world’s top three producer nations; the US, Russia and Saudi Arabia. World production outside these three peaked in 2017 at about 52 mb/d, and has since declined by 6%. “Not every nation other than the big three have peaked,” Patterson reports, “but cumulatively they have peaked.”

Most of Russia’s oil comes from aging fields in Western Siberia that are in decline, and Minister of Energy, Alexander Novak, has warned that Russia’s oil production could drop by 40% by 2035. Saudi Arabia – in spite of threatening to increase production – also appears to be in decline. According to Bloomberg, the giant Ghawar oil field in Saudi Arabia is “fading faster than anyone guessed.” Last year, Saudi Aramco oil company published financial figures, revealing that Ghawar’s historic production has declined by 24% in six years.

Aramco reports a natural decline rate of 8%, which means their production would fall by half in less than nine years, without investing billions annually into new wells and new technology on marginal sites. In 2005, Saudi Arabia increased its operating rig count by 144%, to increase oil production by 6.5%.

According to a 2019 Geological Survey of Finland report, the world average decline rate on post-peak production is 5 to 7%, meaning that oil production could plummet to half its current volume in the next 10 to 14 years.

Over the past decade, only a massive, expensive, noxious, water-and-chemical-intensive fracking campaign in US shale fields has kept the “all liquids” petroleum peak at bay, at least until 2018. However, even this ‘shale boom” is a ruse, made possible by massive debt and unpaid environmental costs.

The shale oil Ponzi scheme

Between 2010 and 2018, average fracking production in the US increased by 28%. That sounds impressive. At the same time, water, sand, and chemical injections increased by 118% – four times faster – leading to massive water and sand depletion, toxic pollution, and mounting debt.

The Finland report points out that “most oil producers in the U.S. tight oil fracked sector have a negative cash flow,” meaning that the investment and operating costs to drill new wells exceed revenues. That study was completed when oil was selling for $55 per barrel. Now, under $30 per barrel, the US fracking industry is unprofitable and crashing.

The US shale industry is essentially a Ponzi scheme, whereby the insiders create companies with massive debt, borrow at cheap rates, operate on a negative cash flow, sell shares in their “booming” companies to a naive public, then get out, making millions in profits while the companies go bankrupt.

Between 2012 and 2017, companies in the Permian oilfield in west Texas – Pioneer, Concho, Cimarex, and others – collectively operated at a $40 billion cash flow deficit. Nearby Eagle Ford field, where production peaked in 2015 and has declined over 25% since, loses about $1 billion per year.

Anadarko, a typical company in the Niobrara shale field in Colorado, has been operating on debt while hemorrhaging cash. Anadarko’s stock price grew from pennies to $112 per share in 2014, making a few insiders filthy rich. Then, burdened by debt, the company stock collapsed. In 2018, Occidental Oil company bought Anadarko for $65 per share, but falling oil prices and the weight of Anadarko’s debt have since reduced Occidental’s value by 85%.

According to Robert Rapier at Oil Price, over the last five years, 208 oil and gas producers and 224 oil service companies – most linked to shale oil schemes – have filed for bankruptcy, abandoning some $209 billion of debt.

Chevron, a notorious climate change denier, recently had to write off $11 billion linked to its unproductive shale oil assets. Chevron’s share price has plummeted over 30% in six months. Since 2016, Exxon Mobil’s stock price has declined by over 50%, a loss of over $200 billion in value.

Tar sands companies are not doing much better. Canada’s Suncor recently announced a $2.8 billion write-down, and in the last 18 months their value has been cut in half. Canada’s Teck Corporation suffered a billion-dollar write-down and then cancelled a $20 billion tar sands project in Alberta.

The end is nigh

According to a 2019 Ozy / Financial Times report, “Investments in oil and gas are tanking,” and energy investors are experiencing a “crisis of faith.” The Wall Street Journal stated that oil companies are “falling out of favor with investors.” Goldman Sachs announced it will no longer finance Arctic oil development over concern for climate change and the fact that drilling and exploring in the far north is risky and expensive.

International petroleum engineer, Jean Laherrère, who worked for 37 years with France’s Total oil company, wrote in 2012, “Technology cannot change the geology of the reservoir,” and Chemist Chris Rhodes wrote in Chemistry World in 2014, “Fracking won’t plug the gap in crude oil’s falling figures. Oil’s exhaustion is inevitable.”

The oil industry is in decline for completely natural reasons. The peak days of cheap, high-quality oil are behind us, and extracting the dregs – shale and tar sands – is expensive, dirty, and catastrophic for Earth’s climate. Ecologists and environmental activists may cheer the demise of oil, since we know that humanity has to reduce its carbon emissions. Nevertheless, there will be a cost to the global economy. According to the Finland report, “approximately 90% of the supply chain of all industrially manufactured products depend on the availability of oil derived products, or oil derived services.” The report warns that the unsustainable economics of the oil industry may crash the entire global financial system.

The oil companies failed to recognize that they should have become diversified energy companies 60 years ago. The price of that failure will now be paid by every human and every other species on Earth. The transition to lower consumption lifestyles and renewable energy systems remains more urgent than ever.

Sources and Links

Finland Report: “Oil from a Critical Raw Material Perspective,” Dr. Simon Michaux, Ore Geology and Mineral Economics, Geologian tutkimuskeskus, Geological Survey of Finland, December 12, 2019: pdf.

Peak oil:

“Exploring Hydrocarbon Depletion,” Jean Laherrère, Peak Oil News, 2012.

“The end of cheap oil,” C.J. Campbell, J.F. Laherrère, Scientific American, JSTOR, 1998.

“The case for peak oil,”Ron Patterson, Peak Oil Barrel, February 13, 2020.

“Peak oil is not a myth,” Chris Rhodes, Chemistry World, 2014.

“U.S. shale has already peaked for major service companies, David Wethe, World Oil, January 22, 2020.

“Peak oil, 20 years later: Failed prediction or useful insight?” Ugh Bardi, Energy Research & Social Science, February 2019.

“A simple interpretation of Hubbert’s model of resource exploitation,” U. Bardi, A. Lavacchi, Energies, 2009.

Resource depletion curve analysis: J. Forrester, World Dynamics, (1971)

“Limits to Growth” report, D.H. Meadows, D.L. Meadows, J. Randers, W.I. Bherens, pdf version.

“The Biggest Saudi Oil Field Is Fading Faster Than Anyone Guessed,” Javier Blas, Bloomberg, April 2019.

“Government Agency Warns Global Oil Industry Is on the Brink of a Meltdown,”

Nafeez Ahmed, Vice / Motherboard, Feb 4 2020.

Oil company bankruptcies and write-offs:

“Oil Bankruptcies Are Reaching Worrying Levels,” Robert Rapier, Oil Price , February 1, 2020.

“Energy Bankruptcy Reports and Surveys, Haynes and Boone, December 31, 2019.

“Why US Energy Investors are experiencing a crisis of faith,” Harry Dempsey, Ozy / Financial Times, 1, 2019

“The Hidden Signs That the Oil Industry Is Heading for a Reckoning,” Geoff Dembicki, Vice , Jan 3, 2020

“Goldman Sachs to stop financing new drilling for oil in the Arctic,” Stephanie Kirchgaessner, Guardian, December 16, 2019.

“Chevron takes-10-billion-charge,” Wall Street Journal, 2020

“Canadian mining giant withdraws plans for C$20bn tar sands project,” Guardian, Feb 24, 2020.

“This 5-year bear market in energy stocks could turn into forever,” Howard Gold, Market Watch, Feb 19, 2020.

“BP warns of third-quarter charges as it spurs $10 billion divestment target,” Reuters, October 11, 2019.

“Schlumberger takes $12 billion charge as CEO charts new course, Shariq Khan, Reuters, October 18, 2019

Oil industry denial:

“United States to lead global oil supply growth, while no peak in oil demand in sight,” IEA, 11 March 2019

No Peak Oil For America Or The World,” James Conca, Forbes, Mar 2, 2017

“Shale Reality Check”, David Hughes, Post Carbon Institute, 2018.

“Technology cannot change the geology of the reservoir, but technology (in particular horizontal drilling) can help to produce faster, but no more,” Jean Laherrere, Peak Oil, 2012.

“Top oil firms spending millions lobbying to block climate change policies,” Sandra Laville, Guardian, Fri 22 Mar 2019

“Fossil Fuel Giants Claim To Support Climate Science, Yet Still Fund Denial,” Paul Thacker, Huffington Post, December 18, 2019.